Ohio History Journal

ROBERT D. ACCINELLI

Was There a "New" Harding?

Warren G. Harding and the

World Court Issue, 1920-1923

In the past ten years a revised, more

flattering image of Warren G. Harding and

his administration has appeared in

historical writing.1 Although many historians

still hold the Harding presidency in low

esteem, a group of revisionists has sought

to upgrade its reputation. These

revisionists do not agree in all respects about

either Harding or his administration,

but they have produced more positive evalu-

ations than previous interpretations.

Their writings indicate that the adminis-

tration, while not without its glaring

defects, had its fair share of accomplish-

ments and originated domestic and

foreign policies which persisted well into the

1920s. Harding himself, once judged a

flat failure and the worst chief executive

in the nation's history, is depicted as

an earnest, hardworking, politically shrewd

President of modest talent and moderate

views-one of the lesser men to occupy

the White House, but not necessarily the

worst.

Refusing to dismiss Harding as an

incompetent, do-nothing President, a num-

ber of writers have contended that he

became increasingly more confident, inde-

pendent, and assertive during his

abbreviated stay in office, and that he signifi-

cantly altered his style of leadership

and his conception of the presidency. They

have argued that upon entering office he

intended to govern in close cooperation

with Congress, his cabinet, and party

leaders, acting as a counselor and concili-

ator rather than as a dynamic chief

executive in the tradition of Theodore Roose-

velt or Woodrow Wilson. His Whiggish

conception of the presidential office and

of executive-congressional relations,

his own personal insecurity and easy-going

nature, and his affinity for harmony

inclined him towards a non-aggressive po-

litical style suited for achieving

consensus and reducing friction. As a result,

however, of a heightened sense of the

responsibilities of his office, greater po-

litical maturity, and the frustration of

coping with a divided and often hostile

Congress, he shifted to a more

forthright posture and came to display greater

initiative and determination in

advancing his domestic and foreign program. By

late 1922 he had become bolder and more

hard-hitting--a "new" Harding had

taken command in the White House.2

1. Louis W. Potts, "Who Was Warren

G. Harding?" The Historian, XXXVI (August 1974), 621-

645, is an excellent survey of

perspectives on Harding since his death. Also helpful for recent apprais-

als is Eric F. Goldman, "A Sort of

Rehabilitation of Warren G. Harding," The New York Times Mag-

azine, March 26, 1972, pp. 42-43, 80-88.

2. Robert K. Murray, The Harding Era:

Warren G. Harding and His Administration (Minneapolis,

1969), 127-128, 376, 422, 533-534;

Robert K. Murray, The Politics of Normalcy: Governmental Theory

and Practice in the Harding-Coolidge

Era (New York, 1973), 22-23, 41-43,

70-73; 75-78, 86-87, 93,

98-99; Andrew Sinclair, The Available

Man: The Life Behind the Masks of Warren G. Harding (Chi-

cago, 1965), 208-211, 240, 245; Francis

Russell, The Shadow of Blooming Grove: Warren G. Harding

in His Times (New York, 1968), 552-553. In spite of a generally

sensationalistic and sour treatment of

Harding, Russell does concede that the

President tried to break from his past in his last months in

office.

Dr. Accinelli is Professor of History at

the University of Toronto.

|

World Court 169 |

|

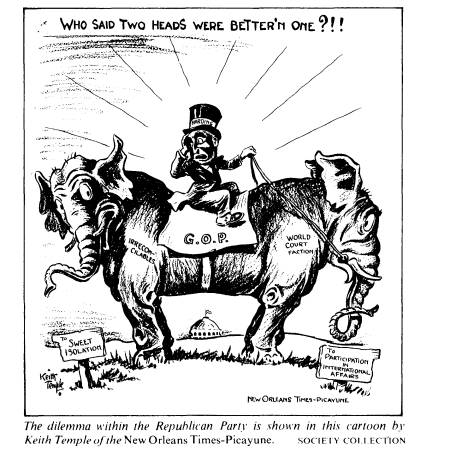

But to what extent had Harding in fact changed prior to his death? Had the burdens and frustrations of power indeed compelled him to shed old attitudes and habits? On the basis of his handling of the issue of membership in the Per- manent Court of International Justice (or World Court), there is reason to ques- tion how much he had changed. His conduct during the struggle over membership demonstrates that he had neither forsaken his conciliatory style nor enlarged his presidential role to the extent of insisting on his own viewpoint in the face of opposition from within the Senate and his own party.3 The Court issue plagued all the presidents of the interwar period, mainly be- cause of the controversy arising from the Court's connection with the League of Nations. First confronted with the issue during the 1920 campaign, Harding,

3. Among Harding scholars, Murray provides the best balanced account of the Court fight; his de- scription of the President's erratic performance is offset by his belief that by 1923 a "new" Harding had appeared who "had become aware of the need for more aggressive and dynamic diplomatic leadership." Murray, Harding Era, 368-374. The same author ignores the fight in his Politics of Nor- malcy but contends that Harding's leadership had markedly improved by late 1922. Sinclair's account of the fight emphasizes Harding's firmness of purpose and his desire to prove his independence of the Senate. Sinclair, Available Man, 274-277. According to Russell, by the last weeks of Harding's life, the Court had become "his . . . dominant and dominating" issue. "Defining himself as he never had before, moving beyond his party in his determination to become leader of his country, he was willing to stake his reputation on the World Court as Wilson had dared to stake his on the League of Nations." Russell, Shadow of Blooming Grove, 581. It is David H. Jenning's contention that the Court fight demonstrates that Harding had changed his mind about the primacy of party and the prerogatives of the Senate in foreign affairs. "President Harding and International Organization," Ohio History, LXXV (Spring-Summer 1966), 161-165. |

170

OHIO HISTORY

adroitly sidestepped the controversy in

the interest of party harmony and his own

election. Once in the White House he

continued this "hands off" approach until

February 24, 1923, when he submitted to

the Senate a proposal for membership

drafted by Secretary of State Charles

Evans Hughes. In the nearly five months

before Harding died a brouhaha erupted

which divided the Republicans and

threatened to disrupt an important phase

of the administration's foreign policy.

For a time Harding championed the

proposal, refusing to capitulate to its critics

in and out of the Senate. Ultimately,

however, his resistance crumbled under

pressure, and he reverted to a strategy

of conciliation, first by forsaking the origi-

nal proposal for an impractical

compromise plan, then by retreating into a smoke-

cloud of ambiguity.

The campaign of 1920 offered a preview

of Harding's later trouble with the

Court issue and of the conciliatory style

he would bring to the White House. By

1920 the creation of a world court had

become not just well-established Republi-

can doctrine but the method of

international cooperation most widely accepted

by the American people.4 Shortly

after the beginning of the campaign, a specially-

appointed Committee of Jurists (which

included Elihu Root, the Republican party

sage and the best known American

advocate of a court) completed a draft-scheme

for the World Court, thus making it a virtual

certainty that an international ju-

diciary would come into existence under

the auspices of the League. Dubbed the

"Root Court" by the press, the

proposed tribunal was a source of potential em-

barrassment for Harding, who was

determined to waffle on the issue of League

membership so as to keep his party

united and ensure his own election. If he em-

braced the Court he would aggravate

those Republicans who wanted him to steer

clear of the League, but if he

repudiated it he would offend those, including the

influential Root, who were not totally

out of sympathy with the League and were

pleased with the establishment of the

Court. "If a 'Root Branch', so to speak, can

be grafted upon the Wilson League,"

reported The Literary Digest in a survey of

Republican press opinion, "the

fruit of the tree will apparently be more to the

taste of many Republicans who have been

telling us not to touch or taste or han-

dle it."5 As Harding and his

advisers perceived, in order to maintain party unity

it would be necessary to devise a

formula acceptable to all factions with regard to

both the League and the Court. To take a definite

stand one way or another on

the Court without taking into account

different opinions about the League would

be politically self-defeating.6

For a time in late August, the Harding

camp considered making the Court part

of a substitute for the League. Will

Hays, the Republican campaign manager,

cabled Root (then still in Europe) for

his opinion of such a plan, only to be advised

that Harding's wisest course was not to

abandon the Versailles Treaty entirely

but to advocate an "Americanized

League" as opposed to the "Wilson League."7

4. Warren F. Kuehl, Seeking World

Order (Nashville, 1969), 280, 340.

5. "A Supreme Court for Quarreling

Nations," The Literary Digest, LXVI (August 14, 1920), 17.

6. Scholars have ignored Harding's deft

management of the Court issue in the campaign. An ex-

ception is Randolph Downes, The Rise

of Warren Gamaliel Harding, 1865-1920 (Columbus, 1970),

ch. 23. My own interpretation differs

somewhat from that of Downes, who fails to appreciate that

Harding's hazy endorsement of the world

court idea was politically useful not only as an alternative

(along with the association of nations

idea) to the "Wilson League" but as a way of avoiding divisive-

ness among Republicans over relations

with the League-sponsored World Court.

7. Will Hays to Elihu Root [no date,

typescript of a telegram], Elihu Root Papers, Library of Con-

gress, hereafter cited as Root Papers;

Root to George Harvey [no date, typescript of a telegram], War-

ren G. Harding Papers, Ohio Historical

Society, hereafter cited as Harding Papers. According to Arthur

Sweetser, an American associated with

the League Secretariat who was in close contact with Root at

this time, Root felt that the Court

could not replace the League because it was limited to legal dis-

putes; he preferred to take the League

as it was, with whatever reservations were necessary, and then

improve it from within, rather than risk

chaos by destroying it. Arthur Sweetser to Eric Drummond,

August 31, 1920, Arthur Sweetser Papers,

Library of Congress.

World Court

171

By vetoing the plan outlined in the Hays

cable, Root obliged Harding to come up

with a somewhat different proposal for

international cooperation. In a speech on

August 28 the Republican nominee offered

as an alternative to the "Wilson

League," an "international

association for conference and a world court whose

verdicts upon justiciable questions this

country in common with all nations would

be willing and able to uphold."

After broadly and vaguely sketching his proposal,

Harding pledged that he would, after his

election, call a conference of the best

men in the country to formulate a plan;

until then he could not be more specific.8

For the remainder of the campaign he

played a series of variations on the themes

introduced in this address. He ignored

the "Root Court," taking no public posi-

tion on possible American membership.

Instead, he embraced the idea of a world

court and often contrasted the coercive,

politically-oriented features of the Cove-

nant with the legalist approach to

international cooperation which was the main-

stay of conservative internationalists

such as Root. Although die-hard Republican

anti-Leaguers remained apprehensive lest

he either endorse the Court or tone

down his criticism of the League now

that the Court was attached to it, Harding

did not budge from his position of

August 28th.9 To do so would have been to

upset the delicate political balance he

sought to maintain and to play into the

hands of the Democrats, who insisted

that the Court was inseparable from and

dependent on the League.10 "I am

for a Court," the Republican candidate as-

sured the powerful Henry Cabot Lodge,

"either under the original plan or, as part

of any new compact which we may make

with foreign countries, but certainly not

as an answer to our objections to the

League."1l

Following his election, Harding met with

Republican leaders in a series of

conferences at his home in Marion, Ohio.

As yet undecided about a concrete

foreign policy program, he nevertheless

took his campaign proposal seriously and

hoped to be able to implement it while

keeping his party, the public, and the Sen-

ate behind him.12 The

conferences confirmed what his campaign experiences had

already made all too obvious--to wit,

that while many Republicans could agree

on the need for a world court,

there were some who had no use at all for the World

Court and others for whom it meant a

great deal.13 When the conferences ended,

Harding's intentions with regard to the

Court were as clouded as ever, and they

remained so after he entered the White

House. Neither in his inaugural address

nor in his message to Congress on April

12 (in which he rejected League mem-

bership) did he provide any clue as to

his plans.14 For nearly two years there was

very little heard from the White House

about the World Court.

Without the assistance of Secretary of

State Charles Evans Hughes, Harding

might not have had an opportunity to

break his silence. Of all the men who headed

8. New York Times, August 29, 1920, 12:2-8.

9. Henry Cabot Lodge to Harding,

September 17, 1920, Henry Cabot Lodge Papers, Massachusetts

Historical Society; Harding to Lodge,

September 1, 1920, Ibid.; Harding to Hiram Johnson, Septem-

ber 6, 1920, Hiram Johnson Papers,

Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley.

10. For statements emphasizing the

relation of the Court to the League by James Cox, the Demo-

cratic presidential nominee, and by

Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby, see New York Times, Sep-

tember 16, 1920, 1:6, September 17,

1920, 10:8.

11. Harding to Lodge, September 20,

1920, Harding Papers.

12. Harding to Frank Brandegee, December

30, 1920, Ibid.

13. Several anti-Leaguers who talked

with Harding, among them Senator Albert Fall of New Mexi-

co and Philander Knox, the senator from

Pennsylvania and former secretary of state, were open-

minded about membership in a court,

providing it was unconnected with the League. New York Times,

December 31, 1920, 1:8, December 16,

1920, 9:1-2. Root, who naturally did not share their views,

came away from a long discussion with

Harding in mid-December in an optimistic mood, hoping that

membership in the World Court would

follow Charles Evans Hughes' installation as secretary of

state. Root to M. M. Adatci, February

22, 1921, Root Papers.

14. New York Times, March 5,

1921, 4:2, April 13, 1921, 1:8.

172 OHIO

HISTORY

the State Department between the wars,

none was more dedicated to the Court

than Hughes.15 It fell to him

to sound out the member-states belonging to the

Court as to the proper terms for

American participation and to formulate the

proposal which Harding sent to the

Senate. Harding presumably kept abreast of

progress towards a proposal, but

remained on the sidelines in this period of

preparation; as was his custom, he

acknowledged Hughes' superior talent and

expertise in foreign affairs by giving

him relatively free rein.

For more than a year, Hughes did nothing

about membership, partly because

the Court was not inaugurated until

January of 1922 but mainly because he was

preoccupied with the separate peace

treaties and the Washington Naval Confer-

ence treaties and felt compelled to

maintain the goodwill of the Senate by re-

maining aloof from the League and the

Court. He was sensitive, however, to

charges from pro-Leaguers that he was

deliberately snubbing both institutions,

and he was aware of a growing sentiment

for membership in the Court.16 On May

6, 1922, a delegation from the Federal

Council of Churches, one of the largest

groups in the peace movement, presented

him with a memorial favoring mem-

bership.17 Although Hughes

contended that entry was not immediately possible,

he not long afterwards received a letter

from a spokesman for the delegation

intimating that the Council would feel

obligated to begin a public movement for

membership even if the administration

were not prepared to act.18 Precisely what

effect the Council's stance had on

Hughes is hard to tell, but it may not have been

coincidental that several weeks later he

initiated discussions with the member-

states. In any event, his decision was

consistent with the thaw in the adminis-

tration's frigid attitude towards the

League, sufficiently advanced by mid-1922 to

permit the State Department to send

"unofficial observers" to meetings of League

agencies.

In early June the Secretary asked

William Howard Taft, then serving as Chief

Justice of the United States Supreme

Court, to make inquiries about member-

ship during an upcoming visit to Great

Britain at the head of a distinguished

group of American lawyers. A leading

Republican, League sympathizer, and a

well-known advocate of a judicial

tribunal, the former President was eminently

qualified to act as a go-between. Not

wanting to work through the League or alert

the anti-Leaguers about possible

membership in the Court, Hughes chose to ap-

proach the member-states privately and

indirectly. Although this process proved

slow and somewhat awkward, it allowed

Hughes to prepare the Court proposal

without fanfare or controversy.

While in Britain, Taft spoke with Sir

Edward Grey, the former Foreign Secre-

tary, with Arthur Lord Balfour, the

British representative on the League Council,

as well as with Robert Cecil, who had

participated in drafting the League Cove-

nant, and with Walter Lord Phillimore,

who had co-authored with Root the plan

which formed the basis for the Statute

of the Court. All agreed that something

could be done to satisfy the two

conditions which Hughes believed indispensable

for membership; first, that the United

States not enter into any official relation

15. Merlo Pusey, Charles Evans

Hughes, 2 vols. (New York, 1951), II, ch. 57, is useful for Hughes'

general policy towards the Court, but

neither he nor any other author has described how Hughes

actually went about preparing the

proposal for membership.

16. Pusey, Hughes, II, 595-597.

Hughes was sensitive about his seeming indifference to the Court.

Hughes to Edwin Gay, August 1, 1922,

Charles Evans Hughes Papers, Library of Congress, hereafter

cited as Hughes Papers.

17. Memorial presented by

representatives of the Federal Council of Churches, May 6, 1922, deci-

mal files, Department of State,

Washington, D.C., 500.C114/172. Materials from State Department

files will hereafter be cited by file

number.

18. William Adams Brown to Hughes, May

15, 1922, 500.C1 14/184.

World Court 173

with the League or incur any obligations

under the Versailles Treaty; second,

that it enter as an equal with the other

member-states, having the right to partici-

pate in the election of judges. (The

Statute of the Court delegated to the Council

and Assembly of the League the right to

elect judges, which meant that the United

States would not automatically share in

this right as did other memberstates, all

of whom belonged to the League.)

Although pleased by Taft's optimistic report

after his return, Hughes remained

uncertain about the best method for securing

membership and he had no time to devote

to the problem, since he was about to

leave on an extended trip to Latin

America.19 Over the next several months it was

Taft who explored the problem in

correspondence with Cecil, Lord Phillimore,

and Root, which was turned over to

Hughes after his return.

With the benefit of the Taft

correspondence and other expert advice, Hughes

was able to formulate a proposal for

membership based on four reservations, the

two most important of which safeguarded

against any relation with the League

or Covenant and permitted participation

in the election of judges. Because of his

careful behind-the-scenes preparation,

Hughes was all but assured that the

member-states would find his terms

satisfactory and he could reasonably hope

for the Senate's approval as well. On

February 17, Hughes sent the proposal to

Harding, reminding him in a personal

note that it was consistent with his cam-

paign statements as well as with the

party platform and assuring him that the

reservations barred any entanglement

with the League.20 A week later Harding

sent the proposal to the Senate. The

upper house was caught by surprise, the only

intimation of the administration's

interest in membership having come four

months earlier in a speech by Hughes in

Boston.21 At that time Hughes had also

consulted Lodge, who remained

noncommittal.22 Neither Hughes nor Harding

apparently made any other attempt to

consult or secure the approval of other

Senate leaders regarding membership.

Moreover, Harding boldly submitted the

proposal only a day after the Senate had

rebuffed him by failing to act upon a

ship-subsidy measure which he strongly

favored. Since only six days remained

before adjournment, the Foreign

Relations Committee postponed consideration

until the next session. Hughes thought

the postponement advantageous because

it would provide a long interval in

which "all pertinent questions may be thor-

oughly discussed and public opinion find

expression."23

If Hughes anticipated a public response

which would swamp all opposition, he

soon had reason to be disappointed. The

next five months were the most turbu-

lent of Harding's presidency. Already

under fire from Republican dissidents for

his domestic views, Harding now had to

withstand an even more damaging as-

sault because of the Court proposal. Not

since the League fight had foreign af-

fairs and domestic politics combined in

such an explosive mixture.

During these months Harding pursued

membership with remarkable zeal con-

sidering his prior history of carefully

guarded ambiguity. He took personal charge

of the proposal, no longer leaving the

initiative entirely in Hughes' hands. His

public statements and private

correspondence reveal him as a well-meaning,

dedicated advocate of membership who was

convinced that the nation could as-

sist in extending the rule of law and

fulfill its obligation to the Court without de-

parting from a middle-of-the-road policy

of cooperation without entanglement.

19. William Howard

Taft to Hughes, July 21, 1922, 500.C114/236; Hughes to Taft, August 1, 1922,

Ibid.

20. Hughes to Harding,

February 17, 1923, 500.CI14/225a.

21. New York Times, February 25, 1923, 1:8.

22. Pusey, Hughes, 11, 598.

23. Hughes to John

Bassett Moore, March 16, 1923, 500.CI14/247a.

|

174 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

If he valued membership for its own sake, he also realized that it could bring political gains as well; with the next election on the horizon, he would not want to disappoint those Americans who admired the Court or have his critics charge that his many campaign endorsements of the world court idea had been empty phrases. As he readily conceded, some sort of Court proposal was necessary as a "political gesture, to give evidence that we are keeping faith."24 Coupled with the Washington Naval Conference treaties, the proposal would demonstrate his ad- ministration's dedication to peace and non-entangling cooperation. Although the evidence is vague, it may also be that Harding considered calling another inter- national conference after the Senate acted upon the proposal, perhaps as a way of making good on his "associations of nations" pledge.25 The fact that Harding was so forthright in submitting the proposal and in as- suming personal control over it confirms the view that he had become more self- assertive by early 1923. Yet the fact remains that his enlarged conception of his

24. Harding to Jonathan Bourne, Jr., April 30, 1923, Harding Papers. 25. In one speech Harding spoke about a "voluntary conference" to bring understanding among nations and codify international law; New York Times, April 25, 1923, 2:2-5. In a letter written in mid-June but not made public until after his death, he denied that his repudiation of the League had "destroyed the hope that there may be found a way to world association and attending world under- standing." Walter Wellman, the journalist who received the letter, said that Harding was determined to have the country perform its international duty and that he wished the Court issue settled so that in the coming year he could issue invitations to a world congress. New York Times, August 27, 1923, 10:8. |

World Court 175

presidential role and the alteration in

his conciliatory style had definite limits.

As the Court controversy grew louder and

more menacing, he became uncertain

and apprehensive, with the result that

the Hughes proposal was left in the lurch

and the entire Court issue thrown into

confusion.

In his dealings with the Court's

critics, Harding always insisted that the vast

majority of Americans were on his side,

and the acclaim heaped on the proposal

seemed to indicate that he was right.

Applauded by many newspapers, the pro-

posal was also endorsed by a wide

variety of national organizations.26 A pro-

Court campaign also got underway through

the peace movement which would

soon make membership the nation's

foremost peace measure.27 Because many

peace groups were pro-League their

support was a mixed blessing for the admin-

istration, which wanted nothing more

than to divorce the League issue from the

Court proposal. Also ranging themselves

behind the proposal were most Demo-

cratic spokesmen, who thus ensured that

it would have bipartisan support. To be

sure, there were a few fervent

pro-League Democrats who sympathized with a

statement issued by Woodrow Wilson

calling for unconditional membership in the

Court and for entry into the League. Yet

most Democratic politicians realized

that there was no profit in rebuffing

the proposal, particularly since party leaders

had praised the Court during the

presidential campaign and since membership

could be construed as a step towards

closer association with the League.28 "It

looks as if we may get in [the League]

on the installment plan," quipped Senator

Gilbert Hitchcock of Nebraska.29 Less

charitable was the waspish Carter Glass

of Virginia, who shrugged off the

proposal as a "harmless thing, the lifting of a

hat to a passerby, so to speak."30

By minimizing the proposal's significance and

playing up the Court's relation with the

League, the Democrats knew they would

irritate the administration. They also

knew that Harding needed their votes to

attain the required two-thirds majority

in the Senate and that he had his hands

full with troublemakers in his own

party. They were content to back the proposal

in their own fashion while the

Republicans squabbled over it.

In spite of the proposal's apparent

popularity and bipartisan character, it at-

tracted a large and noisy contingent of

critics, all of them anti-Leaguers who

found membership in a "League

Court" repugnant and who feared that the closer

the United States got to Geneva, the

greater the danger of being entrapped in

the League itself. The New York

American, the premier daily in the Hearst chain,

warned that Harding was asking the

Senate to "make haste to put the United

States in a position of obedience to a

Supreme Court chosen by and controlled by

the League of Nations. Having refused to

be led into the League of Nations

through the front door, the American

people are now to be squeezed in through

the kitchen door."31 In

agreement with the Hearst press and other anti-League

newspapers were such organizations as

the Ku Klux Klan and the National Dis-

26. New York Times: May 3, 1923,

18:8 (American Federation of Labor); May 11, 1923, 8:3 (Na-

tional Chamber of Commerce); May 17,

1923, 8:1 (National Association of Manufacturers); April 18,

1923, 2:5 (National Republican Club);

April 15, 1923, 2:6 (League of Women Voters); September 1,

1923, 5:1 (American Bar Association).

27. In late May, for example, the

Federal Council of Churches appealed to over 20,000 congrega-

tions to inform their Senators of their

support, Ibid., June 1, 1923, 1:1; and in July the National Coun-

cil for the Prevention of War included

an endorsement in the platform for its "Law-Not-War" Day

which was to be celebrated in over 2,000

communities across the country, Ibid., July 28, 1923, 3:1.

28. Wilson's statement was printed in Ibid.,

April 14, 1923, 1:4.

29. Ibid., February 25, 1923,

1:8.

30. Ibid., April 25, 1923, 1:5.

31. New York American, February

28, 1923.

176 OHIO

HISTORY

abled Veteran's League as well as a trio

of well-known irreconcilables, Robert

La Follette, William E. Borah, and Hiram

Johnson.32

The protests of the anti-Courters caused

a good deal of handwringing among

administration stalwarts, who feared

that the controversy might further divide a

party already at odds over domestic

issues. Not only had the party fared poorly in

the 1922 midterm elections, but a

progressive bloc had emerged in Congress

which was expected to hold the balance

of power in the next session, and there

was talk of a third party in 1924. La

Follette, Johnson, and Borah were in vary-

ing degrees critical of the administration's

domestic program, and each was touted

as a possible presidential candidate.

Yet not only the mavericks were in revolt

against the proposal; it was likewise

denounced by two high party officials, the

chairmen of the Republican Congressional

Campaign Committee and of the Re-

publican National Committee.33 No one

was more distressed about the political

repercussions of the proposal than

Senator James Watson of Indiana, an anti-

Leaguer close to the White House, who

was reportedly working with Lodge and

Frank Brandegee of Connecticut, also an

anti-Leauger, to persuade Harding that

the controversy would split the party.34

Harding's Secretary of War, John Weeks,

was also apprehensive about the

controversy, as was Attorney-General Harry

Daugherty.35

In the face of mounting complaints and

anxiety, Harding remained steadfast

for nearly four months, refusing to

alter the proposal or to abandon the quest for

membership. To his worried secretary of

war he admitted that there were "diffi-

culties and embarrassments" arising

out of the proposal and that he was "not in-

different to the anxiety of my friends

both in and outside the administration";

nevertheless, he added, "I should

be quite without respect for myself ... if I

turned tail and ran away from it [the

proposal] because of threatening political

embarrassments. Most of the opposition

comes from men in the Senate who are

never concerned about the good fortunes

of the present administration, and not a

little of it comes from aspiring men who

are anxious to cause a division in the

party rather than think of the becoming

attitude of this republic in dealing with

the world solution of a problem which we

ourselves introduced."36

During this period Harding, along with

Hughes, Secretary of Commerce Her-

bert Hoover, and Root, laid out the case

for membership and replied to the allega-

tions of the anti-Courters in a series

of widely publicized addresses.37 In a speech in

New York before the annual luncheon of

the Associated Press, Harding denied

wanting to sneak the country into the

League "by the side door, or the back door

or the cellar door." Although

insisting that he did not want to make membership

a "party question," he

contended that the Republican party had often gone on

record in favor of a court and that

"if any party, repeatedly advocating a world

court, is to be rended by the suggestion

of an effort to perform in accordance with

32. "Seeing Ghosts in the World

Court," Current Opinion, LXXIV (May 21, 1924), 651; New York

Times, July 1, 1923, 1:2;16:2. For Borah's views see John

Chalmers Vinson, William E. Borah and the

Outlawry of War (Athens, 1957), 75; for Johnson's, New York Times, March

9, 1923, 1:5;3:4, for La

Follette's, "The World Court,"

La Follette's Magazine, XV (May 1923), 68.

33. New York Times, April 21,

1923, 1:1, "The Republican Rumpus," The Literary Digest, LXXVII

(June 9, 1923), 10-11.

34. New York Times, April 25,

1923, 1:5, 8.

35. Harding to John W. Weeks, April 12,

1923, Harding Papers; Daugherty to Harding, April 24,

1923, Ibid.

36. Harding to Weeks, April 12, 1923,

Harding Papers.

37. New York Times, April 28,

1923, 2 (Hughes); April 12, 1923, 1:1; 6:1-4 (Hoover); April 27,

1923, 7:1 (Root).

World Court

177

its pledges, it needs a new appraisal of

its assets."38

The national response to this speech

pleased Hughes and Hoover, whose sup-

port of Harding's position helped offset

the protests from critics and doubters,

and the President himself thought that

"on the whole" the proposal was now "in

pretty good shape."39 In

order to avoid unnecessary controversy, Harding kept

his own public statements to a minimum

for the next several months, but he con-

tinued to solicit support in numerous

personal letters, in what amounted to his

own private campaign of persuasion.

Directed at influential citizens on both sides

of the issue, the letters left no doubt

that his heart was set on membership and

that he was anxious to remove objections

arising from the Court's relation to the

League.40

In the weeks following the Associated

Press speech, the controversy, instead of

abating, grew more intense. There were

reports that Borah planned to join with

La Follette and George Moses, the New

Hampshire irreconcilable and chairman

of the Senate Campaign Committee, in a

summer campaign against the pro-

posal.41 Even more

dismaying was a letter from Lodge to the Governor of Mis-

souri, made public on April 29, warning

that the Court's relations with the League,

particularly in the election of judges,

posed such serious difficulties that the Sen-

ate might not be content with the Hughes

reservations.42 The Massachusetts

senator was only one of seven Republican

members of the Foreign Relations

Committee who either disapproved of the

proposal or had doubts about it.43 Fol-

lowing a visit to the White House,

Watson of Indiana reported that about twenty-

two senators were disinclined to accept

membership without reservations mak-

ing it plain that the country was not

entering the League.44 Of the few Senate Re-

publicans siding publicly with the

administration, not one was of the stature of

Borah, Lodge, or La Follette. The

proposal's future in the Senate was uncertain

at best. Meanwhile as the controversy

grew more divisive, farm protest raged

through the prairie states, rumors of

scandal gathered around the administration,

and dissension persisted among

Republicans because of domestic issues.

It was under these circumstances that

Harding made an unexpected and un-

wise about-face on the Court issue. Some

time before departing on his "voyage

to understanding" to Alaska on June

20, he decided that a compromise was in

order. Having tried unsuccessfully to

allay fears about the consequences of mem-

bership in the "League Court,"

he sought to quiet them once and for all by rec-

ommending a separation of the Court from

the League. His compromise plan

called upon the League to give up its

administrative relation with the Court, its

exclusive right to request advisory

opinions, and its role in the elections of judges.

The member-states would either conduct

elections apart from the League or,

38. Ibid., April 25, 1923, 2:2-5.

Harding told a friend that his speech was intended to "clarify the

atmosphere" and that he was

especially concerned about "quietly divorcing the International Court

from the League of Nations

proposition." He thought he had done so when the proposal was submitted,

but it now appeared that "a good

many extremists have so persistently urged that this is the beginning

of a fellowship in the League that the

whole situation has been greatly embarrassed." Harding to John

A. Stewart, April 19, 1923. Harding

Papers.

39. Hughes to Harding, April 26, 1923,

Hughes Papers; Hoover to Lewis H. Smith, April 25, 1923,

Herbert Hoover Papers, Herbert Hoover

Presidential Library, West Branch, hereafter cited as Hoover

Papers; Harding to Nicholas Murray

Butler, May 1, 1923, Harding Papers.

40. The letters went to acquaintances

and prominent citizens such as Mrs. Thomas Winters, an

official of the National Federation of

Women's Clubs, Harding to Winters, May 3, 1923, Harding Pa-

pers; and Frank Munsey,

anti-League editor of the New York Herald, Harding to Munsey, May 12,

1923, Ibid.

41. New York Times, May 16, 1923,

21:1-2.

42. Ibid., April 29, 1923, 1:1;

3:1.

43. Ibid., May 16, 1923, 21:1,

May 22, 1923, 4:2.

44. Ibid., June 7, 1923, 21:4.

178

OHIO HISTORY

alternatively, have the judges fill

vacancies with appointees of their own choice.

According to George Harvey, the

anti-League Ambassador to Great Britain who

drafted the plan, Harding was determined

to secure membership, but he wanted

to avoid an inevitable disaster for his

party by uniting it behind a compromise. If

the Democrats rejected the new

arrangement, Harding believed they would re-

veal their insincerity about membership

and forfeit public support.45 It seems

clear that the beleaguered President was

prepared to make major concessions to

the anti-Court faction in order to keep

the party together and to facilitate Senate

approval of membership. Once these

critics were silenced, there were only the

Democrats to worry about, and they

presumably would find it awkward to reject

the compromise without appearing to

place their loyalty to the League ahead of

their support for the Court. As for the

member-states, Harding must have been

persuaded that they would accept his

recommendations for the sake of American

membership. He had been assured by

Harvey that the British would approve

taking the election of judges out of the

hands of the League, and the ambassador

may have offered similar guarantees

about other important member-states as

well. To what extent, if any, Harding

consulted with Hughes about the new plan

is unknown, but it is possible that he

accepted it over Hughes' objection. Accord-

ing to an associate in the State

Department, Hughes approved of the new method

for electing judges but expressed

"considerable doubt whether it would be prac-

ticable from a world point of

view."46 Not one to ignore political realities or the

opinion of the Senate, the secretary

nonetheless could not have been pleased

with a decision to substitute a

cumbersome, hastily conceived compromise for a

proposal to which he had given thorough

consideration and which would satisfy

the member-states.

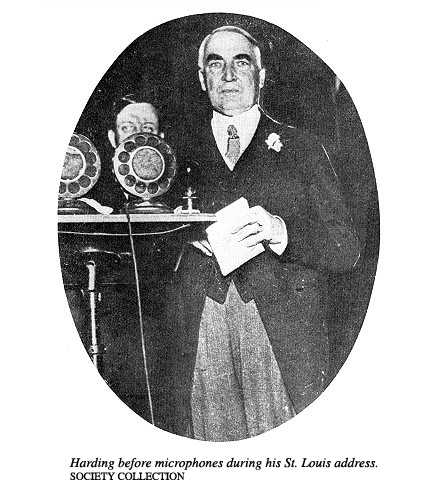

At St. Louis, the first stop on his

cross-country journey, Harding introduced

the new plan to a convocation of ten

thousand Rotarians and a nationwide radio

audience. Disingenuously describing the

plan as an amplification of his original

proposal rather than as a compromise, he

stated that with the Senate's permis-

sion he would begin negotiations with

the member-states in the expectation that

they would understand that he wanted

membership in a genuine world court and

on an equal basis and without loss of

sovereignty. Turning to the Court critics, he

stated that he was "interested in

harmonizing opposing elements" and that he

was "more anxious to effect our

helpful commitment to the court" than he was

"to score a victory for executive

insistence."

I shall not attempt to coerce the Senate

of the United States. I shall make no demand

upon the people. I shall not try to

impose my will upon anybody or any person. I shall em-

bark on no crusade.47

Clearly this was not the militant

Harding of the Associated Press address who

45. Shortly alter Harding died, Harvey

revealed to Calvin Coolidge that he was the author of the

compromise plan. See his memorandum of a

conversation with Coolidge in Willis F. Johnson, George

Harvey: "A Passionate

Patriot" (Boston, 1929), 395. In

another memorandum presented to Coolidge

at that time he outlined the strategy

behind the plan. "The United States and the World Court", en-

closure in Harvey to the President [Coolidge], August

17, 1923, Calvin Coolidge Papers, Library of

Congress.

46. The Diary of William Phillips

[unpublished], June 22, July 6, 1923, Houghton Library, Harvard

University, hereafter cited as Phillips

Diary. Phillips, an Assistant Secretary of State, believed that

Harding's "idea was that if the

Court was self-appointing he might be able to keep the irreconcilables

in line, otherwise our participation

would be doomed; [n.d.], Ibid.

47. James W. Murphy, comp., Speeches

and Addresses of Warren G. Harding, President of the

United States, Delivered During the

Course of His Tour from Washington, D.C., to Alaska and Re-

turn to San Francisco, June 20 to

August 2, 1923 (privately published,

1923), 3747 (hereafter cited as

Harding's Last Speeches).

|

World Court 179 |

|

|

|

spoke, but Harding the conciliator, mindful of the discord in his party, respectful of the Senate, ready to meet his anti-League critics half way. The kindest judgment one can pass on the St. Louis plan is that it was a well- intentioned blunder. While the compromise did silence some anti-Courters, Borah among them, others continued to assail membership, including Johnson and the Hearst press.48 Beside raising doubts among pro-Court Republicans, the plan angered the Democrats, who damned it as impracticable and harmful to the, Court.49 Membership had become a partisan issue and Harding had jeopardized Democratic votes which were indispensable to the passage of any proposal for membership. Signs of distress also appeared in the peace movement; one pro- Courter informed Hughes that the plans of his group for a newspaper poll were collapsing because of opposition to the speech in both parties.50 In the highly un- likely event that the plan had succeeded in uniting the country and the Senate, it

48. New York Times, June 29, 1923, 10:2; "Hiram Johnson's Opening Gun," The Literary Digest, LXXVIII (August 4, 1923), 16; New York American, June 23, 18:1-2. 49. New York Timers, July 1, 1923, VII, 1:3-5. 50. Samuel Colcord to Hughes, August 2, 1923, Hughes Papers. |

180

OHIO HISTORY

still would have foundered because of

objections from the member-states, who

would have been loathe to sever the

Court from the League.51

Unfortunately, Harding's own assessment

of the response to the St. Louis plan

is unknown. Nevertheless it is

significant that he continued to affirm his desire

for membership to audiences on his

"voyage to understanding," but never again

referred to the compromise nor to the

original proposal.52 This suggests that he

thought it expedient to accentuate the

need for membership rather than dwell on

the vexing issue of precisely what terms

he endorsed. Returning to the strategy

of his presidential campaign, he took

refuge in ambiguity so as to protect himself

from politically harmful dissent and

provide time in which to determine a proper

course of action. What course he would

have chosen had he lived there is no way

of telling, but in a major address he

was to have delivered in San Francisco he

intimated that his primary concern was

to find a reasonable and acceptable

method for entry without insisting on

having his own way:

As President, speaking for the United

States, I am more interested in adherence to such

a tribunal [the World Court] in the

best form attainable, than I am concerned about the

triumph of Presidential insistence. The big thing is the firm establishment of the court

and

our cordial adherence thereto. All

else is mere detail. No matter what the critics may say,

we have the obligation of duly

recognizing constituted authority, and I had rather have the

Senate grant its support and have the

United States favor the permanent court than pro-

long a controversy and defeat the

main purpose. I respect the Senate

precisely as I would

have it respect the Presidency, and I

can appraise opposition which is conscientiously in-

spired.53

Still faithful to the principle of

membership, Harding clearly preferred to build

agreement through cooperation with the

Senate, thereby avoiding the contro-

versy a militant strategy would produce.

It is evident from Harding's behavior in the last phase of the

conflict that he

reverted to a strategy of

consensus-building and deference to the power and pre-

rogatives of the Senate which he would

not have considered inappropriate when

he entered the White House. No doubt

recalling Wilson's defeat on the League

issue, he chose to be a conciliator

rather than a crusader. This was a familiar and

comfortable role which had proved

effective in the past in managing the Court

issue. During the 1920 campaign he had

defused the issue by means of a nebu-

lous endorsement of a world court; once

in office, he kept quiet about the issue,

leaving it to Hughes to choose the appropriate

time and method for transforming

the endorsement into concrete policy. It

was a sign of self-assurance and de-

termination on Harding's part that he

submitted the proposal without the ad-

vance approval of Senate leaders and on

the heels of a serious setback in the

upper house on a high-priority domestic

measure. For a time after the controversy

51. Phillips was informed by the French

Ambassador that the member-states would never consent

to the plan. Phillips himself felt that

Harding, in addition to having made membership impossible, had

enormously weakened the nation's

prestige by "giving away so palpably to the irreconcilables";

Phillips

Diary, June 25, 1923.

52. For Harding's remarks about the

Court while on his journey see Murphy, Harding's Last

Speeches.

53. Ibid., 385, italics added.

The San Francisco speech was prepared by the White House staff in

Washington and reached the presidential

party at Vancouver. With Harding's approval, Hoover made

some changes "pledging his

administration to the World Court and to a larger degree of world co-

operation in maintaining peace which I

knew Secretary Hughes would approve." Herbert Hoover,

The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover, 2 vols. (New York, 1952), II, 50. In a memorandum,

"President

Harding's Last Illness and Death,"

dated August 25, 1923, Hoover noted that the speech seemed to

be much on Harding's mind and that he

thought it his most important message on foreign relations;

the memorandum is in the Hoover Papers.

World Court 181

began, he stood his ground, offering

additional proof of a more activist presi-

dential style by taking the proposal

under his own care and by making a substan-

tial contribution to efforts to rally

public support and disarm the proposal's critics.

But as the struggle grew more heated,

the party fell into greater disarray and the

proposal's prospects in the Senate grew

dimmer-all this with a presidential

election in the following year. At St.

Louis Harding took remedial action to silence

anti-League critics and make membership

more palatable to Republican sena-

tors. His compromise plan, while offered

in good faith and under trying circum-

stances, provoked partisan conflict with

the Democrats and jeopardized the

membership he sought to assure. From the

St. Louis speech to his death less

than a month later, conciliation and

ambiguity were the keynotes of Harding's

approach to the Court issue. His San

Francisco statement resembled his 1920

position in its avoidance of specifics

and its insistence on cooperation with the

Senate as opposed to its conformity with

his own viewpoint. His performance in

this final test of his leadership

reveals a President who had, indeed, grown in de-

termination and initiative, yet who

remained a harmonizer, intent on quieting

discord in his own party and on

cooperating with, rather than dictating to, the

Senate. On the Court issue it was the

"old" Harding who gained the upper hand

in the end.