Ohio History Journal

ROBERT EARNEST MILLER

War Within Walls: Camp Chase and

the Search for Administrative Reform

The historical literature about Civil

War military prisons can be di-

vided into three major categories:

prisoners' accounts, accounts of

the camp administrators, and subsequent

historical analyses.1 Inter-

est in how captives lived in these

prisons, North and South, has nev-

er abated. The historian's desire to

find out what prison life was real-

ly like, however, has been frustrated

by the utter disparity between

the accounts of the prisoners and their

keepers. That such a dispari-

ty exists should not be surprising, for

there is seldom a consensus be-

tween the ruler and the ruled. In a

prison environment the absence of

freedom often engenders bitter memories

among its inmates regard-

less of the actual conditions. This

sense of bitterness, which is con-

veyed in most contemporary diaries or

journals of former prisoners, is

often accentuated in accounts written

later in life.2 The official rec-

Robert Earnest Miller is a Ph.D.

candidate in history at the University of Cincinnati.

1. For accounts of the prisoners'

perspective of Camp Chase see: Joe Barbiere,

Scraps From The Prison Table (Doylestown, Pa., 1868), 80-250; W. H. Duff, Terrors

and

Horrors of Prison Life or Six Months

a Prisoner at Camp Chase (New Orleans,

1907),

10-25; John H. King, Three Hundred

Days in a Yankee Prison: Reminiscences of War

Life Captivity (Atlanta, 1904), 4-86; and George C. Osborne, ed.,

"A Confederate Pris-

oner at Camp Chase-Letters and a Diary

of Private James W. Anderson," Ohio State

Archeological and Historical Society Quarterly, 59 (December, 1950), 45-57. The ad-

ministrators' perspective of the

northern and southern prison systems has been pre-

served in R. N. Scott, et al., ed.,

A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and

Confederate Armies in the War of the

Rebellion, 135 vols. (Washington, D.

C.,

1880-1901), 2d. ser., 1-8 (hereafter

cited as War of the Rebellion). The second series is

devoted to the records and

correspondence among prison administrators. Subsequent

historical analysis of Civil War

military prisons has been largely confined to case stud-

ies of individual prisons. See Phillip

R. Shriver and Donald J. Breen, Ohio's Military

Prisons During the Civil War, (Ohio Civil War Commission, 1964), 3-29; Gilbert F.

Dodds, Camp Chase: The Story of a

Civil War Post, prepared for the Franklin County

Historical Society (circa. 1961), 1-5,

available at the Ohio Historical Society (OHS);

and Edward Earl Roberts, "Camp

Chase," (M. A. Thesis, Ohio State University,

1940), 1-56. One notable exception is

the comprehensive and comparative study of the

northern and southern prisons in William

Best Hesseltine, Civil War Prisons: A Study of

War Psychology (Columbus, Ohio, 1930), 34-209.

2. This is particularly true in the

accounts of King and Duff.

34 OHIO HISTORY

ords, inspections, and correspondence

between the local and federal

administrators of the northern prisons

tend to suffer from similar

types of limitations and biases. Thus,

only through a careful sifting of

the two perspectives can the historian

develop a balanced view of

the living conditions in these military

prisons. This essay is an at-

tempt to evaluate the conditions in one

such prison, Camp Chase near

Columbus, Ohio.

One interpretation of prison life at

institutions such as Camp Chase

was offered in William Hesseltine's

classic study entitled Civil War

Prisons: A Study Of War Psychology. Hesseltine argued that living

conditions in the northern prisons

steadily deteriorated throughout

the war. He attributed the poor

treatment of southern prisoners to

a "war psychosis" which

developed in the North. According to

Hesseltine, northern authorities became

convinced, chiefly by news-

paper accounts, that Union prisoners

were being deliberately mis-

treated and even starved to death. The

northern authorities suppos-

edly retaliated against this perceived

mistreatment by consciously, or

unconsciously, abusing their Confederate

captives. During the cen-

tennial celebration of the Civil War,

Phillip R. Shriver and Donald J.

Breen supported Hesseltine's argument.

They suggested that north-

ern prisons reduced the Confederate

prisoners' rations late in the war

in retaliation for the horrid conditions

that existed at Andersonville,

Georgia.3

What happened at Camp Chase, however,

does not conform to

that pattern, for prisoners' living

conditions there generally improved

throughout the war. Although initially

in a state of disorder, Camp

Chase eventually became one of the most

ably administered camps

in the North. Without a doubt the early

years at Camp Chase were

unsatisfactory, but poor provisions and

unsanitary conditions at that

time reflected the general inexperience

of the local prison administra-

tors rather than a conscious design to

mistreat the prisoners. More-

over, this inexperience was exacerbated

by an ongoing conflict

among local, state, and federal

authorities during the early part of the

war. In his brief history of the camp

Gilbert F. Dodds concluded-

and this author agrees-that by 1864 many

of these shortcomings

had been corrected and Camp Chase had

become one of the most

orderly and well-disciplined camps in

the North.4 Dodds does not

explain, however, why it took over three

years for the prison admin-

3. Hesseltine, Civil War Prisons, 173-209,

and Shriver and Breen, Ohio's Military

Prisons, 5-6.

4. Dodds, Camp Chase, 1-4.

War Within Walls 35

istrators to confront and deal

effectively with the problems facing

them.

One way to understand the confusion that

plagued the local ad-

ministrators at Camp Chase, particularly

during the early years of the

war, is to examine the Union

government's virtual unpreparedness to

deal with large numbers of prisoners. At

the outbreak of war in April

1861 the Union government lacked a

comprehensive plan for dealing

with prisoners of war. The ultimate

responsibility of caring for Con-

federate prisoners rested on the

shoulders of Secretary of War Simon

Cameron. By a precedent established

during the War of 1812, how-

ever, that responsibility was in turn

delegated to the Army's quarter-

master general, who was General M. C.

Meigs.5

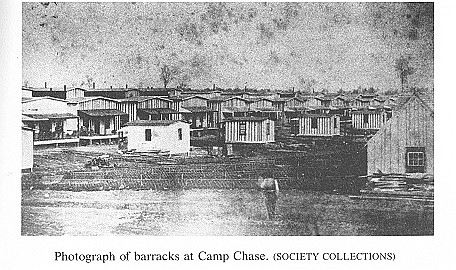

When the ground for Camp Chase was

broken, at the direction of

General William S. Rosecrans on April

19, 1861, the camp was de-

signed primarily to serve as a training

center for new recruits. During

the war the camp took on additional

duties, serving also as a center

for paroled Union soldiers, a place to

muster out soldiers who had

completed their terms of enlistment,

and, of course, a prison for Con-

federate soldiers. Camp Chase, named

after Treasury Secretary Sal-

mon P. Chase, was situated four miles

west of Columbus, Ohio. It

was constructed on flat land, making it

suitable for drilling recruits.

Early in the war, three adjoining

prisons were constructed on its

grounds. The prisons, which occupied

only a small part of the

camp's acreage, were surrounded by

wooden fences about twelve

feet high. Two interior fences divided

the prison area into three rec-

tangular enclosures, unequal in size.6

Throughout the summer of 1861 little

effort was devoted to organ-

izing a cohesive system of military

prisons in the North. Since both

the North and South lacked the

facilities to house large amounts of

prisoners early in the war, alternatives

to incarceration were devised.

Prisoner exchanges were facilitated and

coordinated through mili-

tary Departmental commanders, while

another common practice was

to parole prisoners almost as rapidly as

they were captured. Not sur-

prisingly, then, the first Confederate

prisoners to arrive at Camp

Chase, twenty-three men from the

Twenty-third Virginia Cavalry

Regiment on July 5, 1861, stayed at the

camp for only a few months.

5. Fred A. Shannon, The Organization

and Administration of the Union Army, vol.

II (Cleveland, 1928), Appendix I, and

Hesseltine, Civil War Prisons, 35-38.

6. Dodds, Camp Chase, 4, and War

of the Rebellion, 2d ser., 5:195-208. Although

Camp Chase served a multipurpose role throughout the

war, this study will deal only

with the camp as a military prison.

36 OHIO HISTORY

They were paroled and sent home after

agreeing not to bear arms

again for the duration of the war. This

type of gentleman's agreement

proved to be both unenforceable and

anachronistic as the numbers

of prisoners steadily increased. By the

war's end the aggregate total

of prisoners of war for both the North

and South was over 420,000.7

By the summer of 1861 the number of

prisoners in the North began

to increase. General Meigs convinced

Secretary of War Cameron to

create the position of commissary

general of prisoners, and in October

1861 Lt. Colonel William Hoffman of the

Eighth U.S. Infantry was se-

lected for the position. Ironically, Hoffman

had been one of the first

Union soldiers to be captured by

Confederate troops-in the unsuc-

cessful defense of a Federal arsenal in

Texas in the early months of

the war. Because of his high rank,

Hoffman had problems securing a

quick release from the Confederate

authorities. After obtaining a

parole, however, he accepted his

appointment and quickly went to

work. As commissary general of

prisoners, Hoffman was charged

with organizing and supervising the

military prisons in the North. His

immediate attempts to impose any kind of

standardization over the

existing prisons in the North were

frustrated by Secretary Cameron's

failure to notify Departmental

commanders of Hoffman's appointment

as commissary general. These commanders

frequently exercised their

own discretion in dealing with prisoners

of war.8

Although Camp Chase remained primarily a

center for recruit in-

struction throughout 1861, it was

steadily accumulating a growing

number of military and civilian

prisoners. Political dissidents and

southern sympathizers in Kentucky and

what would soon become

West Virginia were frequently arrested

and sent to either Camp

Chase or a federal post in Wheeling,

[West] Virginia. The civilians,

unlike the soldiers, benefitted from no

means of quick release. Their

stay tended to last much longer than the

military prisoners.9

In December 1861, one such civilian

prisoner, A. J. Morey, editor of

The Cythiana News (Cythiana, Kentucky), provided one of the ear-

liest (and bleakest) descriptions of the

living conditions at Camp

Chase. The prison grounds contained

"about half an acre of ground

inclosed by a plank wall nearly

twenty-five feet high, with towers on

two sides." The prisoners lived in

"two rows of board shanties with

five rooms (16 by 18 feet) in each. In

these small rooms, each oc-

7. William H. Knauss, The Story of

Camp Chase: A History of Confederate Prisons

and Cemetaries (Nashville

and Dallas, 1906), 111, and Hesseltine, Civil War Prisons,

269-79.

8. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 3:156.

9. War of the Rebellion, 2d. ser., 5:195-208.

War Within Walls 37

cupied by about twenty-five men,"

Morey complained, "men of eve-

ry class and grade are huddled together

and treated as felons."

Morey's critique of the prison

environment was as thorough as it was

scathing. The shanties "leaked

badly." Prisoners were poorly clad

and ill-fed. "The food furnished

the prisoners with exception of the

bread was the most inferior kind and in

insufficient quantities for the

sustenance of the famishing men. The

pork was absolutely rotten."10

The slow development of a centralized

federal structure in the

North's prison system helps to explain

the intolerable dietary, sani-

tary, and housing conditions at Camp

Chase. In the early months of

1862 two forces operating against

Hoffman prevented him from quick-

ly establishing an efficient,

hierarchical administrative system. First,

Departmental commanders continued to

exercise jurisdiction over

prisoners captured in their areas and

frequently ignored Hoffman's

directives regarding the treatment and

disposition of prisoners. Sec-

ond, because no clear line of federal

authority had yet been estab-

lished, particularly over some of the

newer prisons, daily administra-

tion of them remained largely in the

hands of local authorities.

It was not until the fall of Fort

Donelson in February 1862 put 15,000

Confederate prisoners in Union hands

that Hoffman decided to

make Camp Chase a permanent military prison.

Over 3000 of them,

largely officers, were sent to Camp

Chase, which helped justify the

change in the camp's status. Despite the

change to a permanent mili-

tary prison, there was relatively little

interaction between federal au-

thorities and the local camp

administrators. One exception to this

occurred in late May 1862 when local

authorities urgently requested

the presence of "regulars" to

suppress the rising insubordination of

the prisoners. Colonel Granville Moody,

the prison's commandant,

was convinced that an uprising was

imminent because the prisoners

were openly defying the established

rules. Colonel H. B. Carrington,

commander of the infantry regiment at

Fort Thomas, just north of Co-

lumbus, responded to Moody's call for

assistance. Carrington later

recalled that conditions at the prison

were as dire as Moody had de-

scribed them. "Occupants of the

different barracks would pelt sen-

tries with hunks of bread; jeer at them

on the sentry platforms, step

across the clearly indicated 'dead line',

sing aloud, and go from

building to building during sleep with

undisguised contempt...."11

10. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 1:543-46.

11. War of the Rebellion, 2d. ser., 5:448 and Colonel H. B. Carrington,

"Official Re-

port of Colonel H. B. Carrington,

Eighteenth U. S. Infantry, to the Governor of Ohio,

June 1, 1862," Printed Materials

Collection, OHS. Henry Beebe Carrington (1824-1912)

helped organize the state militia in

Ohio in 1857. In May 1861, shortly after the war be-

38 OHIO HISTORY

According to Carrington's June 1862

report, the mere presence of the

well-disciplined regular troops in their

full-dress uniforms intimi-

dated the prisoners sufficiently to

restore order.12

News of such problems coupled with

complaints by citizens about

the absence of military authority at

Camp Chase persuaded Colonel

Hoffman to send his aide, Captain H. M.

Lazelle, to inspect the three

prisons at the camp. Lazelle's report of

July 13, 1862, was filled with

disturbing revelations. In the absence

of strong federal leaderhip lo-

cal political and military authorities

had competed for control of the

prisons. Since the camp was originally

formed as a training center for

the state militia, Ohio Governor David

Tod considered himself the

supreme authority over it. Lazelle

reported to Hoffman that Tod "pa-

roles the prisoners within the limits of

the town [Columbus] and

gives instructions to Colonel Allison,

the commanding officer, relating

to their control and discipline."13

Lazelle found Governor Tod anxious to

expand his powers over the

prisons. Conversely, Colonel C. W. B.

Allison, who had just replaced

Colonel Moody, was reluctant to exercise

any authority without the

governor's permission. Lazelle commented

with no small amount of

chagrin that the "commanding

officer of the camp is uncertain and in

constant doubt as to whom he should go

for instructions, which to-

gether with his ignorance of his duties

quite over-powers him."14

The chaotic conditions at Camp Chase

were, then, present in large

measure because the federal authorities

had not yet established a

clear line of authority.

Lazelle described the administrative

structure he found in July

1862. A noncommissioned officer at each

prison was responsible for

nearly every administrative duty; these

ranged from procuring food,

clothing, and necessary supplies for the

prisoners, to maintaining a

clean and healthy environment, as well

as order and discipline.

These men were the only symbols of

authority other than the com-

manding officer. The tremendous scope of

their responsibilities, in

Lazelle's estimation, prevented them

from effectively performing any

one of them.15

gan, Colonel Carrington was put in command

of the Eighteenth U. S. Infantry and was

in charge of the Regular Army in Ohio.

In November 1862 he was promoted to Briga-

dier General. During the war, Carrington

presided over a military tribunal that ex-

posed the activities of the Sons of

Liberty (originally known as the Knights of the

Golden Circle), a secret society of

southern sympathizers and Peace Democrats.

12. Carrington, "Official

Report."

13. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:195-208.

14. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:206.

15. War of the Rebellion, 2d. ser., 5:195-208.

|

War Within Walls 39 |

|

|

|

Lazelle recommended that a more sophisticated administrative structure, one based on that of the Union army, be established for the prisons. A staff of officers would be assigned to work under the commanding officer. These officers were to have specific responsibil- ities: a quartermaster would attend to the physical repairs around the camp, a commissary would weigh and inspect the prisoners' provi- sions, and duty officers would see that the prison grounds were po- liced twice each day. Administrative reform of the prisons offered certain advantages. It helped to define the limits of Tod's authority and subsequently helped to reduce conflict between the governor and the commanding officers at Camp Chase. The federal authorities were also able to establish a better working relationship with the camp's administrators. With better communication between Colum- bus and Washington, a more efficient operation, one more responsive to the prisoners' needs, would result. By the summer of 1862, Colonel Hoffman was recognized as the supreme authority regarding Confed- erate prisoners. More than administrative reform was needed, how- ever, to solve the problems facing Camp Chase.16

16. Ibid. |

40 OHIO HISTORY

Lazelle's detailed report to Colonel

Hoffman in July 1862 de-

scribed other major problems facing Camp

Chase. His inspection re-

vealed, among other things, the

inadequacy of housing conditions in

the prisons. The barracks had been

constructed in 1861 to meet the

immediate demands placed upon the

prisons. The haste in which

the living quarters were built and the

lack of standardization be-

tween them indicated a general disregard

for any long-range plans

involving Camp Chase at that time.17

He made separate reports about each of

the three prisons, begin-

ning with number three, the largest. At

this time, nearly 1100 enlisted

men were held there. The men were

divided into messes of eighteen

men, who were housed in small buildings,

twenty feet by fourteen

feet, scattered across the prison

grounds in clusters of six. Narrow al-

leys separated the clusters. Lazelle

noticed that "all the quarters not

shingled leaked in the freest

manner" and that even the barracks

with good roofs tended to leak through

the sides because of "de-

fects" in the boards.18 His major

concern about the barracks, how-

ever, was the lack of ventilation. This

condition existed because the

foundations of the buildings rested

directly on the ground. Water

gathered underneath the floorboards when

it rained, where it re-

mained. For these reasons, Lazelle

recommended that the floors of

all buildings be elevated at least six

inches above the ground.19

These inadequate housing conditions were

aggravated by the fact

that the prisoners were required to cook

their meals in these small

buildings. Lazelle echoed the prisoners'

complaints when he noted

that the men "are heated to an

insufferable extent by the stove,

which in all weathers, drives the

prisoners to the boiling sun or rain

to avoid the heat."20 By

demanding higher standards for the Con-

federate prisoners of war, Lazelle

demonstrated that the Union army

could be its own worst critic.

Prison number two was much smaller. It

contained about 250 pris-

oners. There were three long buildings

in this prison, each one hun-

dred feet by fifteen and divided by

cross partitions at eighteen-foot

intervals. Two of these barracks were,

in Lazelle's estimation, "well

constructed." They had good

shingled roofs and, most importantly,

their foundations were elevated. The

third building, unfortunately,

had a flat leaky roof and was mired in

the muddy ground. The third

prison, number one, housed about 150

Confederate officers in two

17. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:198-99, and Dodds, Camp Chase, 1-2.

18. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:198.

19. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:199.

20. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:198.

War Within Walls

41

buildings similar to those in prison

number two. Both buildings were

in good repair and were raised off the

ground. A small hospital encir-

cled by a tall fence was also in this

prison.21

Like most visitors to the camp, Lazelle

made note of the poor

drainage conditions and the threat that

they posed to the health of

the prisoners. He reported that "a

terrible stench everywhere pre-

vails, overpowering the nostrils and

stomach of those not impermeat-

ed [sic] with it."22 The

poor drainage conditions of all three prisons

posed a two-fold problem: the flat

ground prevented the runoff of

both rain water and sewage. Governor Tod

and Colonel Allison were

both convinced that this problem had

only one solution. They im-

plored Lazelle to get Hoffman's

authorization to relocate the camp,

but Lazelle turned a deaf ear to this

suggestion. Although drainage

conditions were bad, he felt that they

were correctable.23

Lazelle directed the quartermaster of

the camp to clean out the

main drain of the camp and have it

covered with planks. He asserted

that "the free use of lime at all

times in the privies" would help to re-

duce their stench. He also ordered the

quartermaster to organize the

prisoners for "the digging of

vaults [privies], whitewashing, draining,

grading and constructing roads and walks

in each camp...." 24

Another problem facing the local

administrators in July 1862 was

how to maintain a proper diet for the prisoners.

In his report Lazelle

flatly stated that the provisions and

supplies issued to the prisoners

were "inferior." The beef and

pork were spoiled; the vegetables

were of the lowest quality. The poor

quality of rations was directly re-

lated to the maladministration of the

prisons. One of Lazelle's recom-

mendations for Colonel Allison was to

appoint an officer to be respon-

sible for the commissary. This person

would observe the weighing

and receiving of provisions sold to the

prisons by contractors.25 Ear-

ly efforts by the local administrators

to provide clothing and blan-

kets for the prisoners were equally

misguided. When Captain Lazelle

confronted Colonel Allison with the fact

that many prisoners were in

rags, the latter responded that he intended to "make their

[the pris-

oners'] friends clothe them."26

21. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:198-99.

22. Ibid.

23. One of the natural side effects of

the poor drainage at Camp Chase that left a

lasting impression on many who visited

the camp was the muddy grounds. See War of

the Rebellion 2d, ser., 1:543-546, for an early (1861) description of

these conditions. See

also The Daily Times (Cincinnati),

March 3, 1862, which comments on mud "six inches

deep" and Osborne, ed., "A

Confederate Prisoner," 51.

24. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:201.

25. War of the Rebellion, 2d. ser., 5:202-03.

26. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:199.

42 OHIO HISTORY

Lazelle was initially sent to Camp Chase

to investigate citizens'

complaints about the absence of military

authority at the camp. Pa-

roled Confederate officers, it had been

reported, were allowed to

stroll the streets of Columbus in

full-dress uniform, frequenting the

most expensive restaurants and hotels.

Lazelle did not seem alarmed

at these claims. Perhaps he was

preoccupied with more pressing con-

ditions at Camp Chase.27

When Lazelle arrived at Camp Chase in

July 1862, he was horri-

fied at the complete absence of military

discipline, in every sense of

the word. Not only had Governor Tod

paroled several prisoners to

the city, he had also allowed prisoners

to see their friends in regular-

ly scheduled "interviews." He

had also arranged "for the benefit of

all curious people a regular line of

omnibuses running daily from the

capitol to the quarters." Lazelle

lamented that "the object seems to

be to make Camp Chase popular."28

The carnival-like atmosphere soon

disappeared. Security proce-

dures that fostered discipline and order

were implemented. Prison-

ers were routinely searched on their

initial entry into the prisons, and

officers and enlisted men were

separated. Mail going in and out of the

prisons was inspected before delivery,

and any objectionable refer-

ences were censored. Lazelle helped

upgrade the level of security at

Camp Chase. He instructed the

quartermaster to construct eight

"strong cells" next to the

outer guardhouse to confine disobedient

and violent prisoners. He also ordered

the quartermaster to complete

construction of sentry galleries along

the tops of the outer fence; the

guard watch could then encircle all four

sides of the prisons. During

the summer of 1862, Hoffman kept a

watchful eye on Camp Chase,

making sure that proper security

procedures were employed. He ad-

monished Allison when he learned that

the latter had been offering

rewards for the capture of escaped

prisoners. Hoffman believed that

such a policy encouraged guards to be

careless in their duties so that

they could collect rewards.29

Lazelle had fulfilled his duty of

inspecting the prisons. He had re-

placed an inefficient system of

administration with an hierarchically

structured organization that would be

responsive to Colonel Hoffman

and General Meigs. By enhancing the

military administration at

Camp Chase, the federal authorities

hoped to diminish the power

that Governor Tod exercised over the

prisons.

27. Knauss, The Story of Camp Chase, 232-35,

and War of the Rebellion, 2d. ser.,

3:498-500.

28. War of the Rebellion, 2d. ser., 5:197.

29. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 4:548.

War Within Walls 43

More importantly, Lazelle made several

recommendations to the

local prison officials to improve

housing and sanitary, dietary, and se-

curity conditions. But Hoffman and

Lazelle did not expect these

changes to occur overnight.

Realistically, they expected progress to

be slow. Their feeling was predicated

upon what they felt was an ab-

sence of leadership at Camp Chase. Both

men knew that the best

and the brightest of the Union army's

officers were not drawn to ad-

minister prison camps. In fact, the

first commanding officers at Camp

Chase were not even soldiers. They were

local amateurs masquerad-

ing in their assigned roles. Colonel

Moody was a local Methodist

minister. His successor, Colonel

Allison, was a lawyer, and in La-

zelle's opinion was "not in any

degree a soldier; he is entirely without

experience and utterly ignorant of his

duties and is surrounded by

the same class of people."30

Lazelle returned to the camp in December

1862 for a follow-up in-

spection. During the interim, Colonel

Allison had resigned his com-

mand. Before Lazelle could attend to his

inspection, he was con-

fronted with the news that Major Peter

Zinn, Allison's replacement,

was resigning on December 31. This rapid

turnover of commanders

left young twenty-four year old Captain

E. L. Webber in charge of the

prison.31

Lazelle's evaluation of the prisons was

now surprisingly favorable.

He reported that the barracks were in

"excellent condition, both as

regards to police and repair, with two

or three exceptions in the roofs

of these buildings which I directed to

be remedied." He found the

prison hospital "well supplied with

wholesome food, cooking uten-

sils, fuel, medicine, and bedding."

He was also impressed with the

extent of improvement in the quality of

the prisoners' food. Lazelle

was probably gratified to see that some

of his organizational sugges-

tions had become realities. Direct

supervision of the receipt of food

by the commissary improved the quality

of the provisions and elimi-

nated the corrupt practices of the

contractors. Lazelle noted that

from "personal inspection and

conversation with prisoners I am satis-

fied their food is wholesome and not in

a single instance did I learn of

a complaint as to the quality and

quantity of the food." Likewise, he

found "exceedingly few who were not

sufficiently clothed." If they

had the means to do so, prisoners could

supplement their normal ra-

tions; a sutler operated a stand in each

prison, and sold a variety of

goods, mostly food items, including

apples, potatoes, onions, cab-

30. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:197.

31. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:132.

44 OHIO HISTORY

bages, parsnips, and turnips. Lazelle

concluded that the sutlers' sup-

plies were "proper and suitable,

both in variety and quality."32

By December 1862 the number of prisoners

at Camp Chase had

dipped to 293, all of whom were placed

in prison number two. In the

nearly six months since Lazelle's

previous visit, over thirteen hun-

dred prisoners had been exchanged. This

exchange system, how-

ever, broke down in the spring of 1863,

and was suspended until the

final months of the war when southern

defeat was imminent. Conse-

quently, during the later years in the

war, prisoners' internment was

lengthened and prison facilities in the

North as well as the South

were taxed beyond their limits.

Meanwhile, with a manageable num-

ber of prisoners, the amateur

administrators had an opportunity to

organize the security of the prison.

Sentinels on parapets that rested

on the twelve-foot-high fence stood

guard over the prisoners. During

the night the four inside corners of the

prison were lit by "ordinary

street lights, thus placing the whole

prison at all times under the sur-

veillance of the guard," according

to Lazelle, "insuring the complete

security of the prisoners."33

For the most part, Lazelle was satisfied

with the progress the pris-

on administrators had made. Real

improvements could be seen in

the living quarters, health care, and

the quality of provisions issued

to the prisoners. Lazelle indicated

disappointment, however, that

the commanding officers had failed to

regularly whitewash the bar-

racks. Also, some of the barracks had

not yet been elevated. Most

importantly, the local authorities had

failed to address the poor

drainage conditions. Lazelle's suggested

measures of grading and

draining the grounds had not been

consistently effected.34

The prison population continued to

decrease throughout the spring

of 1863. Prisoners were continuously

being transferred north to John-

son's Island, on Lake Erie, and east to

Forts Warren and Delaware, in

Massachusetts and Delaware respectively.

In April 1863 over 500 Con-

federate prisoners were transferred to

Fort Delaware, thus enabling

Captain Webber to provide separate

accommodations in prison num-

ber three for three Tennessee women

accused of spying.35

Conditions at the prisons seemed to be

gradually improving during

the spring of 1863. Major General

Ambrose E. Burnside, command-

32. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:133-35, 202-03, and Dodds, "Camp Chase," 3-4.

33. Randall, J. G. and Donald, David, The

Civil War and Reconstruction (Boston,

1969), 333-39; Duff, Terrors and

Horrors of Prison Life 11-12; and War of the Rebellion,

2d. ser., 5:135.

34. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:133.

35. War of the Rebellion, 2d. ser., 5:247, 448.

War Within Walls 45

ing the Department of the Ohio, issued

General Order No. 36 on

April 21. This order revoked the parole

Governor Tod issued to sev-

eral Confederate officers who had been

captured in the fall of Fort

Donelson.36 Exactly at the

time order was being restored to the pris-

ons, Colonel Hoffman ironically

complained to Burnside about the

"great want of discipline" at

Camp Chase. Hoffman's complaint was

ambiguous; he claimed that there was a

need for "better discipline

and better control" but did not

refer to any particular grievance. Nor

did he identify the source of his

information. In the same note to

Burnside, Hoffman revealed his intention

to transfer the remaining

prisoners at Camp Chase.37

News of Hoffman's decision did not

formally reach Camp Chase

until May 11, 1863. Secretary of War

Edwin M. Stanton and Hoffman

desired to convert the prisons into a

temporary place of confinement

for military prisoners, with one of the

smaller prisons to remain as a

holding center for political prisoners.

Hoffman was confident that

prison number three, which had recently

been closed, would never

open its gates again.38 The

reasons for this sudden decision to re-

duce the role of Camp Chase remain

unclear, but the consequences of

the decision were clear. For a short

time, from May to July 1863, the

federal authorities were undecided as to

what role Camp Chase

would play during the remainder of the

war, and during this brief pe-

riod very few improvements in its

facilities occurred. Federal authori-

ties were reluctant to authorize

expenditures for improving a prision

that might be of little value in the

future.

In May, Brigadier General John Mason, commanding

Union forces

near Columbus, was granted the authority

to authorize release of all

deserters from the Confederate army to

help facilitate a reduction of

prisoners at the camp.39 Consequently,

the prison population at Camp

Chase was reduced to 380 by the end of

June 1863. During the

month of July, however, the camp

received more than two thousand

prisoners.40 Nearly half of

these men had been under the command

of General John H. Morgan of Kentucky.

During one of his raids,

Morgan was captured near New Lisbon,

Ohio. He was sent to the

state penitentiary, but most of his

soldiers were sent to Camp Chase.

36. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:504, 517.

37. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:593.

38. War of the Rebellion, 2d. ser.,

5:448.

39. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:593.

40. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 8:986-1003. By July 1862 most of the prisons in the

North had adopted a uniform system for

reporting monthly prisoner rolls to Washing-

ton. These monthly reports offer useful comparative

data among the northern prisons.

46 OHIO HISTORY

Evidently, the reputation of the raiders

preceded their arrival at

the camp; their presence "stirred

up the camp beyond all calcula-

tions."41

Throughout the summer and fall of 1863

Hoffman continued to de-

pend on the reports of his inspectors to

help shape his opinions

about the living conditions in the

northern prisons. A. M. Clark, Act-

ing Medical Inspector for Prisoners of

War, made a tour of the military

prisons in the fall. On his inspection

of Camp Chase on October 31,

1863, Clark found the prisoners' health

to be "tolerably good"-

only fifteen of the 2145 prisoners were

patients in the hospital. Clark

found the prison structures to be in

generally good physical condi-

tion but complained about an almost

total lack of ventilation. He was

also disappointed with the current

commanding officer, Colonel Wil-

liam Wallace of the Fifteenth Ohio

Volunteers, who, like his prede-

cessors, had not seriously attempted to

correct the prisons' "utterly

inefficient" sewage and drainage

conditions. He attributed the pris-

ons' two prevalent diseases, pneumonia

and diarrhea, to the poor

sanitary conditions.42

After another inspection of the prisons

on January 7, 1864, Clark

suggested to Hoffman that the health

conditions of the guards at

Camp Chase, members of the Eighty-eighth

Ohio Volunteer Infan-

try, were not much better than those of

the prisoners. Hoffman was

especially irritated that four cases of

varioloid had recently broken

out among the guards, only to be met

with virtual inaction by the

camp's acting medical officer. Clark

said that "no measures had

been taken to prevent the spreading of

the disease." He quickly or-

dered a sufficient supply of vaccine for

the "immediate vaccination of

every person in or connected with the

camp...."43

In January 1864 Hoffman was informed

that four prisoners at Camp

Chase had been shot to death. He

requested Colonel Wallace to in-

vestigate these shootings personally,

and to submit detailed reports

to him regarding each incident. Instead,

Wallace delegated the

chore to his second-in-command, Lt.

Colonel A. H. Poten. Accord-

ing to Poten's reports, two of the

shootings, one in September and the

other in November 1863, occurred because

the prisoners refused to

stand away from the fence; after being

warned to move, these men

were shot. This was a common security

procedure among the military

41. Letter from Private John Lyndes,

July 25, 1863, available at OHS.

42. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 6:479-80.

43. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 6:819. Varioloid was a mild strain of smallpox that

usually manifested itself in people who

had been vaccinated or previously had small-

pox.

|

War Within Walls 47 |

|

|

|

prisons in the North. It was the other two shootings that concerned Hoffman. In both of these cases sentinels fired their guns into bar- racks when prisoners refused, after repeated warnings, to extinguish their light.44 Hoffman was not satisfied with Poten's explanations. He felt that they were "very unsatisfactory, being vague or general and without any evidence to support them."45 Poten's reports, moreover, con- tained an alarming tone. The case of Henry Hupman, of the Twentieth Virginia Cavalry, who was fatally wounded in his barracks demon- strated Hoffman's concerns. Poten reported that "as sad as this case may be, to wound a perhaps innocent man . . . it has proved to be a most excellent lesson, very much needed in prison-No. 1-as the rebel officers confined in that prison showed frequently before a dis- position to disobey the orders given them by our men on duty. They have since changed their mind."46 Hoffman was worried that secu- rity procedures had become too strict at Camp Chase, and he was concerned about the welfare of its prisoners. On January 29 he wrote Wallace again, ordering him to relieve Poten of his duties, pending further investigation of the necessity of the shootings. Hoffman was aware of mistreatment of Union soldiers in the southern prisons, and he was anxious to avoid duplicating such treatment in the North. In

44. War of the Rebellion, 2d. ser., 6:1058. 45. War of the Rebellion, 2d. ser., 6:892. 46. War of the Rebellion, 2d. ser., 6:854. |

48 OHIO HISTORY

his letter to Wallace, Hoffman stated:

"The rebels have outraged

every human and Christian feeling by

shooting down their prisoners

without occasion and in cold blood, and

it is hoped that Union sol-

diers will not bring reproach by

following their barbarous exam-

ple."47

What began as a simple request for

information on Hoffman's part in

January escalated into a full-scale

inquiry into the security procedures

of the prisons that dragged on until

mid-March 1864. By that time,

Wallace had been relieved of command at

Camp Chase. On March

17, Hoffman informed Secretary Stanton

about the "gross neglect of

duty" on the part of Colonel Wallace.

In two cases "where the senti-

nel had fired into the barracks in

consequence of a light in the stove,

the circumstances were not such as to

justify such harsh meas-

ures. ..."48 Not surprisingly, one

of the first actions taken by the

new commanding officer, Colonel William

Pitt Richardson, was to is-

sue a list of standardized regulations

for the sentinels at Camp Chase.

This list spelled out the duties and

responsibilities of the sentinels

while on duty. It defined a chain of

command and stated the justifia-

ble uses of firearms against prisoners.49

Richardson had been severely wounded in

his right shoulder at

Chancellorsville in May 1863 and was

inactive until he was sent to

Camp Chase in early 1864. He greeted his

new assignment as the pris-

ons' commandant with enthusiasm. As

Wallace's successor, Rich-

ardson saw room for improvement in the

administration of the pris-

ons. Richardson took steps to improve

the health of the prisoners.

One prisoner, James W. Anderson, who

arrived at Camp Chase in

April 1864, recalled that upon his

arrival, he and the men he was

travelling with received the standard

issue of clothing, "one blanket,

one change of underclothing, and clean

shirts," and were ordered

by the provost marshal, Lieutenant S. L.

Hammon, to wash them-

selves. The following day Hammon

inspected the prisoners. One of

the men had not washed and was locked up

in a small cell all day.

Personal hygiene was thus enforced

daily, and the barracks were

swept to prevent the spread of vermin.50

47. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 6:892-93.

48. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 6:1058.

49. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 7:1. Under these new regulations the guards' use

of firearms was restricted severely. In

lesser violations, as in the previous case of Henry

Hupman, the guards were now required to

call on the sergeant on duty before acting.

50. Osborne, ed., "A Confederate

Prisoner at Camp Chase," 55. Richardson, a vet-

eran of the Mexican War, received his commission of

Major of the Twenty-fifth Ohio

Volunteer Infantry when he helped raise

two companies. Richardson was appointed

War Within Walls

49

Colonel Richardson also improved the

quality of the prisons' water

by having the wells deepened to fifteen

feet. He did little initially,

however, to correct the camp's poor

drainage and sewage problems.

Throughout the war the local authorities

were convinced that only

one alternative existed: Camp Chase must

be relocated to an area

with better natural drainage. Repeated

efforts by the local authori-

ties to convince Hoffman of the absolute

need to move the prisons

had failed. In the spring of 1864

Richardson tried a new tack and pe-

titioned Hoffman to move only one

prison, number three, from the

east end of camp to the west where

natural drainage was more suita-

ble. Hoffman, a cautious and thrifty

administrator working within

the constraints of a tight budget, was

reluctant to do so, as relocating

even one prison would be costly.

Nevertheless, Hoffman had two dif-

ferent men investigate the feasibility

of moving the prison at Camp

Chase. Neither report, the first in May

1864, the second in the fol-

lowing August, endorsed relocation. Both

suggested that the drain-

age and sewage problems could be

corrected at a minimum expense,

with the labor being performed by the

prisoners.51

Despite efforts to professionalize the

prison guards through in-

creased organization and standardized

policies, Richardson was

forced to inform Hoffman of one of the

most embarrassing escape at-

tempts in the history of Camp Chase.52

On July 4, 1864, several pris-

oners in prison number three rushed a

seldom-used and poorly

guarded gate as a wagon was exiting from

the prison. Twenty-one men

escaped but were recaptured almost

immediately. One of the es-

capees, Private Ezekial A. Cloyd from

Tennessee, was shot during

the attempt. His wound subsequently

forced amputation of his arm

above the elbow. Hoffman, outraged,

demanded that the guard be

increased each shift and that the

sentinels be additionally armed

with revolvers. While this was a hard

lesson for the 895 officers and

commander of the post early in 1864, and

he remained in that position for the duration

of the conflict. In the fall of 1864 he

was elected as the state's attorney general.

Richardson was rewarded for his efforts

to improve the living conditions at Camp

Chase when in December he was promoted

to Brevet Brigadier General. See White-

law Reid, Ohio in the War: Her

Statesmen, Her Generals, and Soldiers, vol. 2 (Cincin-

nati, New York, 1868; reprint edition

Columbus, 1893), 945-46.

51. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 7:51-52; 108-09 and 529-30.

52. Authorities conflict on the number

of escape attempts by the prisoners. Knauss

referred to an attempt in 1861 but

offered little information in The Story of Camp Chase,

111; King described two allegedly

successful escapes that seem doubtful, if not unbe-

lievable, in Three Hundred Days in a

Yankee Prison, 82; James Anderson described a

continual process of clandestine

activity that was constantly foiled by informants.

Osborne, ed., "A Confederate

Prisoner at Camp Chase," 48. All authors agree, how-

ever, on the attempt committed on July

4, 1864.

50 OHIO HISTORY

men of the Eighty-eighth Ohio Volunteer

Infantry, Richardson and

his men learned from their mistakes. No

escape attempts of a compa-

rable magnitude were attempted during

the remainder of the war.

More heavily armed guards, plus the

construction of an outer fence

encircling the entire camp in the fall

of 1864, frustrated most plans for

escape.53

Colonel Richardson supervised what he

termed a "total rebuild-

ing of the camp and prisons" by the

end of August 1864. Prior to that

period, it must have been disconcerting

to members of the Sixteenth

and Twenty-fifth Louisiana Regiments

Consolidated who were

marched into prison number two during

this period of reconstruc-

tion. One of those men, W. H. Duff,

recalled that "there were no

shelters of any kind only a few tents

which were occupied by prison-

ers already there before we came.54

The condition did not last long.

New barracks were constructed in prisons

number two and three be-

fore the chill of winter arrived.55

Two other prisoners, John H. King and

James W. Anderson, who

arrived four months prior to Duff,

witnessed the entire process of re-

construction. They were able to observe,

if not appreciate, the tre-

mendous transformation in the physical

conditions of the barracks.

King noted that although the quality of

the structures had im-

proved, it was not long before they

became overcrowded. The new

quarters were constructed just in time

to accommodate the steady in-

flux of new prisoners who arrived in the

fall of 1864. From the end of

July through October, the number of

prisoners dramatically rose

from 1881 to 5458. 56

Anderson described his new living

quarters in prison number

three as a small room, about twenty-four

feet square, with a stove in

the middle. Bunk beds occupied about

one-third of the floor space.

The overcrowded conditions in his

barrack caused Anderson to

comment in his diary that "we are

just about as thick as we can be to

'Stir with a Stick'." Anderson was

transferred to prison number one

in December, where he remained until his

release in February 1865.

The transfer proved to be advantageous.

Prison number one retained

53. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 7:474; 584-85; and 591. See also Francis P. Weisen-

burger, Columbus During the Civil War

(Ohio Civil War Commission, 1964), 16-20, who

argued that the outer fence was

constructed around the camp to contain the Union sol-

diers' means of egress, not as a

security measure aimed at the prisoners. This argument

is supported in War of the Rebellion,

2d. ser., 7:529.

54. Duff, Terrors and Horrors of

Prison Life, 12.

55. Ibid., 14.

56. King, Three Hundred Days in a

Yankee Prison, 179.

War Within Walls 51

its original structures but increased

its acreage during the rebuilding

period in 1864.57

Improvements in the prisons' sanitary

conditions in August 1864

were equally as significant as the

reconstruction of the barracks.

The drainage and sewage problems that

had plagued Camp Chase

throughout the war were finally resolved

with the construction of a

large reservoir in prison number two. A

prisoner's letter described

the new system: "Prison No. 2 had a

large reservoir that contains sev-

eral hundred gallons which is filled

each day and loosed to carry

away the filth that accumulates in a

deep planked ditch thereby

keeping things quite clean."58

During the same period in August 1864,

efforts to grade and drain

the prison grounds were again renewed.

During his stay at Camp

Chase, from August 1864 to February

1865, W. H. Duff remembered

that "the ground was at all times

well drained."59

The inspection officer of the camp, F.

S. Parker, reported on Sep-

tember 3, 1864, that the efforts of

Colonel Richardson helped to

change Camp Chase from a

"detestable mud hole to a healthy well-

organized camp."60 Without

question, the elimination of stagnant

water and filth from the prison did much

to improve the health con-

ditions of the prisoners. That these

improvements were long overdue

cannot be denied. It took over three

years to adopt Lazelle's sugges-

tions for improving the prisons'

sanitary conditions. An unwillingness

among the local administrators to deal

effectively with the drainage

problems, and their insistance of

relocating the prisons, partly ex-

plains the delay. Also, Colonel Hoffman

was reluctant to make any ex-

penditures late in the war unless

absolutely necessary.

Richardson also supervised efforts to

feed and clothe the prison-

ers properly. Two diametrically opposed

viewpoints suggested that

neither the prisoners nor their keepers

were satisfied with the prison-

ers' rations. B. R. Cowen, Adjutant

General of Ohio, reported to

Stanton in August 1864 that "the

sleek, fat, comfortable looking reb-

els were never better fed nor more

comfortably situated." "This

may," he continued, "account

for their resting so quietly under their

confinement." Cowen felt that the

prisoners were being granted ex-

cessive indulgences. Many of the

prisoners were receiving gifts of

food from friends, which Cowen felt was

"an unpleasant contrast to

57. Osborne, ed., "A Confederate

Prisoner at Camp Chase," 55.

58. Ibid.

59. Duff, Terrors and Horrors of

Prison Life, 12.

60. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 5:135.

52 OHIO HISTORY

the treatment received by our soldiers

now languishing in southern

prisons."61 Conversely,

John H. King recalled in his memoirs during

the same period of the war that the

administrators at Camp Chase

were actively and consciously involved

in starving the Confederate

prisoners to death. "This

starvation plan," King recalled, "brought

about the results which our barbarous

enemies desired. The consti-

tutions of the helpless prisoners,

however robust, were soon broken

down."62 If Cowen's

views represented Hesseltine's "war psycho-

sis" of the North, King's remarks

were imbued with a postwar psy-

chosis that infected much of the South.

Both Cowen and King were

using the issue of the prisoners'

rations to express their attitudes

about the war and the enemy.

James Anderson offered a more tenable

description of the prison-

ers' rations. He described a typical

meal: "At one time the fare con-

sisted of one-third of a pound of light

bread, four ounces of beef,

beans, and soup." Anderson added

that "though this was no feast,

it was enough to cultivate a good

appetite." While this prisoner some-

times complained of hunger, he reasoned

with himself that eating

more food in his present state of

idleness would probably "breed

disease."63

During the late summer of 1864 the local

administrators helped to

improve the general health of the

prisoners by issuing a new set of

clothing to them. Even King, who was

critical of almost every other

aspect of prison life, admitted that

"as far as clothing, bedding, and

other apparel were concerned, we managed

to get through the sum-

mer months without any real suffering."64

August 1864 clearly represented the

pinnacle of administrative effi-

ciency at Camp Chase. Federal and local

authorities were responding

to the needs of their prisoners, and

reforms in housing and sanitary

condition, both long overdue, were

finally enacted. Colonel Rich-

ardson stated with obvious pride and

satisfaction that "the prison-

ers present a healthy appearance, being

very much improved since

their arrival at this post, having

comfortable clothing and good

healthy rations."65

The prison administrators, however, were

unprepared to deal with

the thousands of new prisoners, many of

whom arrived in tattered

rags. Problems in procurement hindered

Richardson's efforts to

61. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 7:530.

62. King, Three Hundred Days in a

Yankee Prison, 76.

63. Osborne, ed., "A Confederate

Prisoner at Camp Chase," 49.

64. King, Three Hundred Days in a

Yankee Prison, 74.

65. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 7:699.

War Within Walls

53

clothe these recent arrivals. In October

he had to issue government

shoes, normally reserved for Union

soldiers, to barefooted prisoners.

He complained to Hoffman in November

that the supply of prisoners'

clothing was inadequate. Richardson's

concern for the welfare of his

prisoners was admirable. Moreover, such

humanitarian actions late in

the war totally contradict the notion of

"war psychosis" as a guiding

force of prison administrators.

Richardson's request for a better sup-

ply of clothing did not go unheeded.

According to Anderson, during

the winter of 1864, he and all prisoners

were issued "one blanket, one

change of underclothing, and a suit of

common grey pants and coat."

He confided in his diary that he did not

personally suffer from the

chilling winds because he had plenty of

clothes, a fair share of blan-

kets, and comfortable quarters.66 Anderson

could have easily been

content to sit out the remainder of the

war in relative comfort.

The gravest challenge facing Camp

Chase's administrators in the

fall of 1864 was an outbreak of

smallpox. Introduced into the prisons

in May of that year, it reached epidemic

proportions by that fall.

Richardson's report to Hoffman, in

October, revealed that "the

smallpox is prevailing in the prisons

averaging ten cases per day." A

small building called the "pest

house" was constructed outside of

the prison walls to quarantine the

disease.67 In early November

Richardson reluctantly reported that

while "every precaution is

taken to prevent smallpox it is brought

in by new arrivals and cannot

be guarded against."68

But in December he reported to Hoffman

that "the health of the prisoners

is improving. Measures now adopt-

ed will soon eradicate smallpox."69

Several improvements in sanitary

conditions, some with the aid of federal

authorities and others inde-

pendent of it, helped attenuate the

effects of the disease, and the

battle against smallpox ended in victory

for the local administrators.

It also represented a private triumph

for W. P. Richardson. Once de-

scribed as "intelligent but not

very active in the discharge of his du-

ties" by Lt. Colonel John F. Marsh,

a subordinate attached to the

Army's inspector-general's office,

Richardson had proved worthy of

this challenge.70

66. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 7:972, 1097, and Osborne, "A Confederate Prison-

er at Camp Chase," 49.

67. Duff, Terrors and Horrors of

Prison Life, 19-20; King, Three Hundred Days in a

Yankee Prison, 86-90; Osborne, "A Confederate Prisoner at Camp

Chase," 56; and War

of the Rebellion, 2d. ser., 7:971-72.

68. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 7:1097.

69. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 7:1189.

70. War of the Rebellion, 2d.

ser., 7:108-09

54 OHIO HISTORY

The war began to wind down during the

winter of 1865, but the

prisoners remained restless. Tensions

increased in January as the pris-

on population swelled to over 9000.

Anderson wrote in his diary

about an incident in which forty or

fifty prisoners "were fixed to

charge the guards and escape, but when

the slightest demonstration

was made shots were fired."

Anderson noted that one man was

severly wounded in the thigh and others

lost all their money and

fine clothing as a result. Typically,

prisoners caught trying to escape

lost any extra privileges they might

have accumulated. When the in-

stigators could be discovered, they were

removed from the prison

and placed in solitary confinement.71

By this late date in the war some

prisoners began to turn their at-

tention to the day they would be

released. The final entry of Ander-

son's diary, dated January 18, 1865,

reflected his eagerness to return

home. "So I end My pilgrimage in

these parts and go to [the] field of

a fairer clime."72 The

first prisoners were not released as a unit,

however, until February 12, 1865. A

parole exchange was arranged

between Union and Confederate

authorities, initially only for non-

commissioned officers and enlisted men,

but one for officers soon

followed. W. H. Duff and members of his

regiment were among the

first 500 prisoners to be released. They

left the camp "with glad

hearts."73 John King was

also released in February. To his "inex-

pressable joy," he was able to

leave the "long detested prison that

for three hundred weary days had been my

horrible lodging

place."74

The overcrowded conditions that existed

from January to March

1865 had a direct impact on the health

of the prisoners. In January

the prisons contained over three times

their recommended capacity.

In February the mortality rate of the

prisoners peaked at over five

percent; in this one month alone 499

prisoners died. When the war

ended in April there were still over

5000 prisoners at the camp. These

remaining prisoners were slowly released

throughout the spring. Fi-

nally, on July 5, 1865, the commanding

officer at Camp Chase notified

the War Department that the last few

Confederate prisoners had

been released.75

It was by the fall of 1864 that Camp

Chase, according to one histo-

rian, had become one of the most orderly

and well-organized camps

71. Osborne, "A Confederate

Prisoner at Camp Chase," 56.

72. Ibid., 57.

73. Duff, Terrors and Horrors of

Prison Life, 23.

74. King, Three Hundred Days in a

Yankee Prison, 96.

75. Dodds, "Camp Chase," 2.

War Within Walls 55

in the northern prison system.76 The

orderliness of the camp was a

reflection of the administrative

efficiency that had developed at

both the local and federal levels. That

developmental process was

complete by August 1864. A working

partnership between the Office

of the Commissary-General of Prisoners

and the local administrators

at Champ Chase emerged out of the

maladministration and chaos of

the early months of the war. Together

they were able to improve sev-

eral aspects of the prison environment.

Necessary reforms in the pris-

oners' rations, housing, and sanitary

conditions and the security of

the prison were implemented. That many

of these reforms occurred

late in the wars suggests that living

conditions actually improved,

rather than declined, as the war reached

its final stages. Many of the

improvements also occurred while reports

indicated that conditions

at Andersonville prison were worsening

day-by-day.

Neither the conditions at Andersonville

nor a "war psychosis" in-

terfered with the local or federal

authorities commitment to improv-

ing the prison environment at Camp

Chase. Three factors, however,

helped delay the rate of improvement in

the living conditions at the

prisons. First, Colonel Hoffman failed

to establish a clear line of au-

thority over the northern prisons until

1862 when, as a first step in ad-

ministrative reform, he sent Lazelle to

Camp Chase to reorganize the

prisons' administrative structure in

order to make it more responsive

to the needs of the prisoners. That this

initial effort did not occur un-

til July 1862 helps explain the prisons'

early chaos.

Second, the constant changes of command

at Camp Chase also de-

layed the rate of improvement in the

living conditions. Despite the

centralization of authority in northern

prisons by mid-1862, the fre-

quent turnover of the prisons'

commanding officers prevented an ef-

fective partnership between local and

federal authorities. It was not

until March 1864, when Colonel

Richardson became the permanent

commander of Camp Chase for the duration

of the war, that long-

standing deficiencies in living

conditions could be properly ad-

dressed. Under Richardsons's command,

reforms encompassing

nearly every aspect of prison life were

speedily enacted.

Third, fluctuations in the prison

population led federal authorities,

from May through the end of July 1863,

to believe that the northern

prisons should be consolidated. During

this period Camp Chase's

worth was in question, and it was not

clear whether the prisons

would remain. While the prisons' status

remained in question, all at-

tempts by the federal authorities to

improve the housing and sanitary

76. Ibid., 4.

56 OHIO HISTORY

conditions were delayed. By July 1863

Stanton and Hoffman read-

justed their estimates of the number of

Confederate prisoners they

would have to accommodate, and any plans

to consolidate the north-

ern prisons were shelved. But Hoffman

continued to be reluctant to

authorize large expenditures for the

prisons unless "absolutely neces-

sary." It was not until August

1864, for instance, that Hoffman author-

ized the reconstruction of the barracks.

What cannot be emphasized

enough, however, is that improvements in

prison conditions, no mat-

ter how gradual, eventually occurred.

While a "war psychosis" may

have existed at some levels of the

Union army and government, it was

anything but a guiding force in

the office of the commissary-general of

prisoners. It is reasonable to

assume that Hoffman's policies for Camp

Chase were not at great vari-

ance with those for the several other

prisons in the North. The rec-

ord at Camp Chase, at least, suggests

that relative progress in the

prisoners' conditions, rather than

decline, occurred late in the war.