Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

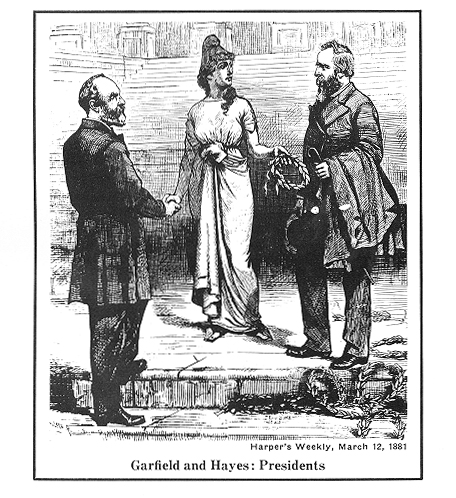

Garfield and Hayes: Political Leaders of the Gilded Age by ALLAN PESKIN They are linked together in the public mind: Garfield and Hayes, along with Grant, Arthur and Harrison--bearded Presidents for a Gilded Age. To Thomas Wolfe, "They were the lost Americans: their gravely vacant and bewhiskered faces mixed, melted, swam together . . . . Which had the whiskers, which tile burnsides: which was which?"1 Others besides Wolfe have had difficulty in sorting out the men from behind their beards. Garfield and Hayes are especially troublesome. Not only did they look alike, but their early careers were uncannily similar. Born less than ten years and a hundred miles apart, both were reared with- NOTES ON PAGE 195 |

112 OHIO HISTORY

out a father. Both were first educated

in academies, then in small Ohio de-

nominational colleges, and then each

went East to finish his studies. Both

were just beginning to make a name in

local politics when the Civil War

broke out. Both led Ohio regiments in

battle and both accumulated im-

mense political capital from their

wartime feats.

Their careers ran on parallel tracks,

which is perhaps why they never

collided. Even though they had similar

backgrounds, came from the same

region and engaged in the same line of

work, James A. Garfield and Ruth-

erford B. Hayes were never intimate--nor

were they rivals. Their lives

occasionally intersected and at times

twined together, but, considering

their geographic and political

proximity, the two remained surprisingly

distant in their personal relations.

They did not even know each other well

until after the Civil War, even

though they had nearly been

comrades-in-arms. Shortly after Hayes had

been appointed major in the Twenty-Third

Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Gar-

field was offered a lieutenant-colonelcy

in the Twenty-Fourth.2 Had he ac-

cepted, he and his fellow Ohioan would have

trained together at Camp

Clase and campaigned side by side down

the Kanawha Valley. Instead,

Garfield took command of the

Forty-Second O.V.I. and served in the west-

ern theater of war. He left the army for

Congress late in 1863, and Hayes

followed his example two years later.

There the two Ohioans finally came

together--as Republican Representatives

in the critical post-war period.

Their first meeting was not auspicious.

Arriving in Washington in De-

cember of 1865 to take his seat in

Congress, Hayes took the measure of his

future colleagues at a caucus of Ohio

Republicans. Garfield made a poor

showing. Hayes dismissed him as "a

smooth, ready, pleasant man, not very

strong,"3 and the two

had little to do with one another during the course

of Hayes's brief congressional career.

While Hayes was inconspicuously filling

his seat on the back benches of

Congress, Garfield was winning

reputation as "the coming man" of his

state and party. In the spring of 1867,

some of his friends urged him to

save the party at home and launched a

Garfield-for-Governor boom which

won the support of over forty Ohio

newspapers. His close advisers, how-

ever, warned against the movement,

suggesting that after another term in

Congress, he might be in line for a

Senate seat. Garfield did not really

need to be persuaded. His inclinations

led him to prefer the excitement

of national politics, and his talents,

which were intellectual and oratorical

rather than administrative, were better

suited to Congress than to the

governor's chair. Furthermore, he was

sick from overwork--"dizzy, stupid

sick"-and needed a European rest to

avoid complete collapse.4 Under the

circumstances, a political campaign was

out of the question. Garfield spiked

the gubernatorial boom and urged (without

enthusiasm) the renomina-

tion of his good friend, Jacob Dolson

Cox. Instead, the nomination went

to Hayes, and with it he laid the

foundation for his future political career.

In the next few years, the demands of

politics would draw Garfield and

Hayes closer together. They cooperated

in the campaigns of '68 and '69

GARFIELD and HAYES

113

and exchanged friendly letters from time

to time. When his second term

was nearing its close, the Governor

urged Garfield to be his successor.

Though flattered, the latter was not

eager "to make the sacrifice" unless

the party demanded it of him. For one

thing, he explained, "my tastes do

not at all lead me in that

direction," but more to the point, he could not

afford to take a thousand dollar cut in

salary.5 As he confided to a friend,

"it would almost ruin me

pecuniarily to be a candidate .... Governor

Hayes has lived as economically as any

Governor of Ohio ought to live,

and it has not cost him less than $6000

a year. At the end of my term

(should I be elected) I would be almost

broken up financially."6 By 1871

Garfield was a leading figure in

Congress, chairman of an important com-

mittee, with an unlimited political

future. Why step down to an under-

paid, ornamental office? "Any

Justice of the Peace in Cleveland has more

to do than the Governor of Ohio,"7

Garfield observed, and he endorsed

Hayes as just the man to fill the post

for another term. "He is an exceed-

ingly efficient Governor, and his

conduct has always been wise and pru-

dent."8

But Hayes had had enough of politics for

awhile and turned to his per-

sonal affairs. In the next few years he

suffered a series of political setbacks

that seemed to finish his public career.

Nominated for Congress in 1872

against his better judgment, he was

defeated as a consequence of the Greeley

movement. Grant rewarded his loyalty

with an insultingly inferior office

which Hayes spurned as "small

potatoes."9 To add to the insult, this nom-

ination which Hayes did not even want

was rejected by the Senate. Mean-

while, Garfield was steadily moving into

a position of party leadership in

the House of Representatives. His

political career was clearly running in

advance of that of his fellow Ohioan.

By 1875 both Hayes and Garfield had come

to regard Grant as a disaster

for their party. Hoping to block a third

term for the President, Garfield

advised a reconstruction of the

Republican party along anti-Grant lines.

As an essential step, he suggested,

"We must put forward an unexception-

able man for governor. I think we ought

to take Hayes."10 This time his

colleague accepted the call and in the

ensuing campaign endeared himself

to Garfield by championing his pet

cause: sound money. "Your ideas as to

our true policy are precisely

mine,"11 Hayes assured Garfield.

Soon after Hayes had won his third term,

Garfield's political scouts re-

ported that the Governor's name was

being mentioned for the presidency.

Some thought the nomination of the bland

Ohioan would be stronger at

the polls than that of the better known

but more controversial party lead-

ers. "It is alleged by those in

favor of Hayes that no story will stick to him

to his injury, that he was born lucky on

that score and is just the kind of

man to run because no nickname or slang

phrase can be pinned to him."12

Garfield encouraged the Governor's

hopes. "I am greatly gratified at the

way you are bearing yourself during

these preliminary months of platform

and president making," he wrote.

"I have believed from the beginning

that . . . we should give you the solid

vote of the Ohio delegation and await

the break which must come as the weaker

candidates drop out."13

114 OHIO HISTORY

Hayes was deeply moved by Garfield's

support,14 but failed to realize

how ambiguous it was. To Garfield, Hayes

was one of those "weaker can-

didates" whom he expected to fall

by the wayside. As he told a friend, "I

do not find that the mention of his name

excites much enthusiasm outside

of Ohio. He would make an eminently

respectable President, and I should

be glad on many accounts to see him elected.

Still, he certainly would not

be the strongest man we could

choose."15 Garfield hoped to use Hayes as

a stalking horse to hold the Ohio

delegation together until it could swing

its strength at the proper moment to his

real choice, James G. Blaine.16

To further this plan, he encouraged

Blaine supporters to go to the conven-

tion pledged to the Governor but ready

to switch when Hayes weakened.17

Blaine, however, weakened first, and

Hayes was nominated in spite of

Garfield's doubts.

Garfield immediately pledged his support

to the nominee and bom-

barded him with good advice. He urged

Hayes to wage his campaign on

the issues of civil service reform and

resumption of specie payments.18

When he read the letter of acceptance,

"a very clear and sensible docu-

ment,"19 he was

flattered to see that what he thought were his suggestions

had been incorporated.20 As

the campaign progressed, the two differed

over strategy. The candidate thought the

party should stress more emo-

tional issues, such as the danger of

handing over the government to the

rebels and the public schools to the

Catholics. He repeatedly pressed the

Catholic issue on Garfield and suggested

that it should be raised in every

speech.21 Garfield could not get overly

excited about the Catholic menace,

but the specter of a Democratic victory,

he confessed, "fills me with alarm

and apprehension."22 He

suspected that the Democrats would try to steal

the election and shuddered at the

possibility of such an "irretrievable

calamity."23

Holding such a partisan commitment,

Garfield was placed in a delicate

position when President Grant asked him

to witness the count of the re-

turns in the disputed election of 1876

in Louisiana. There he found to

his own satisfaction, at least, that his

earlier suspicions of fraud were con-

firmed. On his return from Louisiana, he

called on Hayes and assured him

that he had won the state legitimately,

despite Democratic skulduggery.24

The Democrats, however, were not so

easily persuaded. When Garfield

reached Washington, he found the capitol

buzzing with threats of a civil

war if Tilden should be counted out; but

Garfield was not alarmed, for

he had developed a strategy to resolve

the dispute. As he explained to

Hayes: "two forces are at work. The

Democratic businessmen of the coun-

try are more anxious for quiet than for

Tilden, and the leading Southern

Democrats in Congress, especially those

who are old Whigs, are saying

that they have seen war enough and do

not care to follow the lead of their

Northern associates who as Ben Hill says

'were invincible in peace and

invisible in war.' " He had been

approached by southerners who had broad-

ly hinted that in return for internal

improvements and a less militant Re-

publican Negro policy they would not

only support Hayes's claim to the

presidency, but they might even consider

supporting a new Republican

|

GARFIELD and HAYES 115 party in the South based "on the great commercial and industrial ques- tions rather than on questions of race and color."25 He asked for advice, but the tight-lipped Governor, who never committed himself on paper if he could avoid it, laconically replied, "Your views are so nearly the same as mine that I need not say a word."26 This was encouragement enough. Garfield and others proceeded to work out an understanding with southern Democrats along the lines Garfield had originally laid out, and the way seemed clear for Hayes to become President. |

|

As soon as he was finally installed in the White House, the new Presi- dent conferred with Garfield. As part of the understanding that had been reached with southern Democrats, there was a faint possibility that enough of them might be detached from their party to enable the Republicans to organize the House of Representatives. In that event, Garfield would be the next Speaker. But the appointment of John Sherman to the Cabinet had created a vacancy in the Senate, and, according to Garfield's scouts, he had the best chance to this office. The President, however, asked him to forego the Senate and help him in the House, thus clearing the way for Hayes's old college chum, army comrade and political crony, Stanley Matthews27 to make a bid for the Senate seat. Garfield was "a little nettled" at the request,28 but, like a good soldier, was ready to do his duty. "It is due to Hayes that we stand by him and give his policy a fair trial," he ex- plained. "On many accounts I would like to take that place [the Senate seat]; but it seems to fall to my lot to make the sacrifice."29 If the Presi- dent insisted, Garfield would renounce his ambition. The President did |

116 OHIO HISTORY

insist, and on March 11 Garfield wired

his supporters in Columbus to

withdraw his name. Three days later,

when it seemed for the moment that

Matthews might not win, Garfield was

flabbergasted when Hayes casually

suggested that perhaps he should run for

the Senate after all. Garfield

ruefully told him that it was too late.30

Later that year, Garfield's suspicion

that he had been duped was con-

firmed. As he told his diary, on

November 24, "today, Stanley Matthews

told me that he had no thought of

running for the Senate until Hayes

suggested it. That he replied it

naturally belonged to Garfield who would

probably be nominated at any rate. To

this the President replied that it

could be amicably arranged. So after

all, the public view is the correct

one that Hayes inaugurated his

[Matthews'] candidacy."31

The maneuverings of Hayes on the

senatorial question were a bad omen

for Garfield's relations with the

President he had helped to elect. Worse

would follow. In the politics of the

Gilded Age, the power to award pa-

tronage was the best measure of

influence. Garfield found, to his dismay,

that all patronage doors were slammed in

his face. For over a month after

the administration began, he vainly

tried to obtain a Treasury Department

post for his old friend Horace Steele.

Instead, the job was given to a friend

of a Cleveland Congressman. Garfield

wrote Hayes a scolding letter,32 but

received no satisfaction. When he

suggested a friend as commissioner to

the Paris Exposition, Hayes personally

objected; and even though Garfield

"rather sharply" told the

President he was being unfair, his wishes were

ignored.33 In 1877 another friend,

John Q. Smith, was removed from his

position as Indian Commissioner at the

insistence of Carl Schurz, the Sec-

retary of Interior. Garfield took Smith

to the White House and told the

President that his treatment "had

been outrageous and unjust." Hayes was

unmoved and the Congressman regretfully

concluded, "He does not seem

to be master of his administration. I

fear he has less force and nerve than

I had supposed."34

Smith was ultimately consoled with

another office, but, as a result of

these rebuffs, Garfield was convinced of

the President's ingratitude. To a

constituent who asked him to exert his

influence for a favor, Garfield sadly

confessed his impotence: "It is

almost hopeless to try to secure such ap-

pointments through Congressional

influence, as the President pays very

little attention to the wishes of

members, and in my own case, has never

yet made but one single appointment on

my application."35 Since ap-

pointive offices were the currency of

politics, it was clear to Garfield's

friends that he was being shortchanged,

considering all he had done for

the party and for Hayes, personally.

They were indignant that the Presi-

dent was taking such advantage of

Garfield's "good nature and generosity,"

and felt he had been "snubbed and

ill treated" by the administration.36

Part of this estrangement, however, was

Garfield's fault. He was psycho-

logically incapacitated for having a

close friendship with any president.

Even though he and Hayes had once been

on good terms, as soon as the

latter was inaugurated, it seemed as if

a veil dropped between them. "It

GARFIELD and HAYES

117

must be that there is an innate

reverence for authority in me," Garfield

reasoned. "I remember how awful in

my boyhood was the authority of a

teacher."37

Furthermore, the two men were poles

apart in temperament. As Presi-

dent, Hayes was somber, austere and

forbidding in his personal relations.

In many ways more polished and

sophisticated than the rustic Garfield,

Hayes nonetheless lacked the younger

man's playful inquisitive mind,

which could marvel that Hayes was so

humorless as to fail to laugh at

Don Quixote or even at the Pickwick

Papers.38 Garfield, on the other

hand, was as sentimental and effusive as

a schoolboy. He liked to throw

his arm around a friend's shoulder and

call him "Old Fellow"! Hayes

would have reacted to such crude

familiarity with a disdainful shudder.

Close personal friendship between the

two was out of the question, but

respect was not impossible.

The growing gulf between them was caused

by more than mere person-

ality differences. Garfield was becoming

increasingly disturbed at the drift

of Hayes's policies. His disquiet began

with the appointment of the Cabinet.

Although he admired Secretary of State

Evarts personally, he distrusted

his "dreamy doctrines."39

He considered the appointment of Carl Schurz

"unfortunate and unwise,"

because of the Interior Secretary's record of

party irregularity.40 The elevation to

the Treasury of John Sherman, whom

he had always distrusted and disliked,

"was not satisfactory to me," he

announced.41 Nor did he

approve of Hayes's experiment of putting an

obscure southerner in the Cabinet as a

gesture of reconciliation. Hayes, he

observed, "should either take none

at all or the greatest .... I fear he is

not quite up to this heroic

method."42

Garfield's major policy disputes with

the administration were over two

issues for which he had once held tile

highest hopes: northern reconcilia-

tion with the South and civil service

reform. When southern Democrats

failed to support him for Speaker of

tile House, Garfield lost some of his

enthusiasm for sectional reconciliation.

Even more disturbing were the

signs that Dixie leaders remained unrepentant

despite concessions. "The

policy of tile President has turned out

to be a give-away game from the

beginning," Garfield told a

carpetbagger friend. "He has . . . offered con-

ciliation everywhere in the South while

they have spent their time in

whetting their knives for every

Republican they could find." He blamed

all the trouble on tile President's

"weakness and vacillation."43 Finally,

in exasperation, Garfield "took

occasion to speak very plainly to the Presi-

dent," and warned him that his

gestures to the South were splitting the

party.44

Garfield's quarrel concerning civil

service policy was over means, not

ends. As he told Jacob Dolson Cox:

"You and I were among the earliest to

urge Civil Service Reform. We cannot

afford to see the movement made a

failure by injudicious management."

The Congressman particularly re-

sented Hayes's practice of giving his

old army friends office while preaching

against the spoils system. "If

nobody is to be appointed because he is your

118 OHIO HISTORY

friend or my friend," he complained

to Cox, "then nobody should be ap-

pointed because he is any other man's

friend. The President himself should

exercise the same self-denial as other

officials."45 Garfield objected to some

of the civil service regulations as

silly and unwise, but, more than that, he

thought the President was tackling the

problem from the wrong end. Rather

than a piecemeal reform of the system by

executive decree, Garfield thought

that a thorough-going reform through

congressional legislation was the only

way to place government service on a

permanent and rational basis. As it

was, he could find no system behind

Hayes's policy. "The impression is deep-

ening that he is not large enough for

the place he holds,"46 Garfield sadly

concluded on the first anniversary of

the Hayes administration.

Baffled and frustrated, Garfield watched

what he thought was an admin-

istration sliding into chaos. "I am

almost disheartened at the prospect of

getting anything done by the

President," he lamented to an Ohio editor in

1878. "Day by day the party is

dropping away from him, and the present

state of things cannot continue much

longer without a total loss of his in-

fluence with the Republicans. The

situation is gloomy enough I assure

you."47 He tried to warn the President of

the dangers facing the party, but

Hayes complacently found comfort in the

support he had from every col-

lege president and every Protestant

paper.48 "It seems to be impossible for a

President to see through the atmosphere

of praise in which he lives,"49

said Garfield in exasperation. Although

he had nothing against college pres-

idents or Protestant ministers (he had

been both himself), he knew that

the support of the party professionals

was much more important to the

success of the beleagured

administration. But as Garfield listened to the

widespread grumblings of Republican

discontent, he feared that Hayes

would prove "an almost fatal blow

to his party." In fact, he himself was on

the verge of a public break with the

President.50

He was not alone. Indeed, it seemed to

Garfield as a party leader that

the Republicans in Congress were falling

apart. "The tendency of a part

of our party to assail Hayes and

denounce him as a traitor and a man who

was going to Johnsonize the party was

very strong, and his defenders were

comparatively few," Garfield later

recalled. He pleaded with his colleagues

to give the President's policies a fair

trial, and, in order to forestall an open

rupture, he deliberately avoided calling

a party caucus for six months hop-

ing, in the meantime, to find an issue

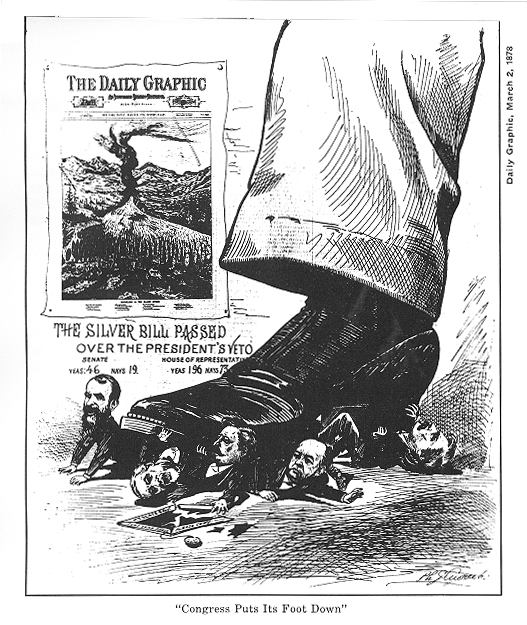

that would unite the party.51 Even so,

early in 1878 Garfield found himself the

only Ohioan, and virtually the

only midwestern Congressman who voted to

sustain the President's veto of

the compromise Bland-Allison silver

purchase bill. In fact, the veto was

overridden by a greater majority than

had supported the original Bland

House bill, demonstrating to him how

little influence Hayes had with Con-

gress. "He has pursued a suicidal

policy in Congress," Garfield declared,

"and is almost without a

friend."52

In September of 1878, Garfield

accompanied the President on a speak-

ing tour of Ohio. He could hardly fail

to notice that Hayes was as unpopu-

lar with the people as he was with the

party. There was no cheering when

he stepped off the train at Willoughby,

and the sullen coolness of the crowd

|

towards their Chief Executive embarrassed Garfield.53 Indeed he was be- coming more and more sympathetic with the plight of the beleaguered Pres- ident. Garfield always did have a soft spot in his heart for underdogs. In his own stormy political career he had suffered inordinate abuse, and as a re- action he usually felt compelled to defend anyone who was attacked. His new respect for Hayes, however, was based on something more substantial than pity. In fact, the two Ohioans had drawn closer in recent months, with the President turning more and more to Garfield for advice. Early in 1879, Garfield advised him to veto a Chinese exclusion bill which had the strong support of his political rival Blaine.54 Hayes took the advice, and with Garfield's management the veto was sustained. Garfield was Hayes's manager also in a great running battle with the Democratic Congress over the issue of the use of federal power to protect Negro voters at southern polling places--a battle which required seven rapid-fire presidential vetoes before the Democrats finally surrendered. |

120 OHIO HISTORY

At this stage in Hayes's administration

any victory was welcome. Never

particularly popular, even from its

inception, it had by now seemingly run

out of steam. If tile party were to

avoid dissension and collapse, a fresh issue

would have to be found. But the failure

of southern conciliation and the

success of specie resumption had

deprived Hayes of two of his most cher-

ished issues, while a third, civil

service reform, threatened to divide the

party and alienate needed support.

Furthermore, with the Democrats in

control of the House of Representatives,

any legislative program would

probably be thwarted. Garfield turned

this last drawback into an advantage,

however. By goading the House Democrats

into an unwise defense of states

rights and white supremacy, he was able

to portray them as unreconstructed

rebels, unworthy of the nation's trust.

Hayes's dream of sectional reconcilia-

tion was laid to rest, the bloody shirt

was taken out of mothballs and waved

once more; but the Republican party was

able to close ranks behind the

familiar issues of the Civil War and the

President won luster as a resolute,

plucky defender of national unity and

integrity.

During the struggle Garfield was at the

President's elbow every step of

the way, stiffening his resolve.55 He

was so delighted with the outcome that

he even named his dog "Veto."

He had reason to be pleased. The Congress-

man along with the President had given a

tired, riven party a fresh issue

around which it could unite, and

Garfield himself had emerged as a lead-

ing spokesman for an administration

which had once snubbed and rejected

him. He was especially proud of the

confidence Hayes now gave him. "I

think I have never had so much

intellectual and personal influence over him

as now," he boasted. "He is

fully in line with his party."56 A few months

later, as the administration was drawing

to a close, Garfield could summon

up a charitable evaluation of Hayes that

would have been unthinkable two

years earlier: "Whatever his

critics may say, he has given the country a very

clean administration and his party has

not been handicapped . . . by any

scandals caused by him."57

Although Hayes had occasionally hinted

to Garfield that he might be

presidential timber, he never imagined

that Garfield would be his success-

or.58 But when that news came from the

Chicago convention, Hayes was

delighted. "You will receive no

heartier congratulations today than mine,"59

he wired his party's new

standard-bearer. The nomination of Garfield, he

declared, "was the best that was

possible. It is altogether good." In part,

this reaction was due to local

pride--"Ohio to the front also and again"--

but, more than that, it was a source of

personal satisfaction. The choice of

Garfield, who was so closely identified

with his administration, was an en-

dorsement of Hayes personally; while, if

the nomination had gone to Grant

or Blaine, it would have been regarded

as a repudiation of his work.60

Furthermore, Garfield had been one of

the men responsible for Hayes's

election through his efforts in the

Louisiana investigation, the Electoral

Commission, and the compromise

negotiations preceding the inauguration.

If voters approved of Garfield, they

would also be ratifying Hayes's title to

the Presidency, and the cruel title,

"His Fraudulency," which had haunted

him for four years could at last be

exorcised.

GARFIELD and HAYES

121

Now it was Hayes's turn to tell Garfield

how to run for President. He

reasoned that about every twenty years

the nation was ripe for an election

waged on personalities. Garfield, he

thought, was the "ideal candidate" for

such a campaign, "because he is the

ideal self-made man." The President

envisioned a canvass conducted with all

the hoopla of the famous "Log

Cabin and Cider" campaign of 1840.

Garfield's inspirational rise from ob-

scurity should be trumpeted across

America. "Let it," he urged, "be thor-

oughly presented--in facts and

incidents, in poetry and tales, in pictures,

on banners, in representations, in

processions, in watchwords and nick-

names."61 The candidate himself

should stay discreetly in the background,

just as he had done four years earlier.

Garfield's only role should be "to sit

crosslegged and look wise until after

the election."62 The taciturn Hayes

enjoined complete silence on his

would-be successor: no speeches and, above

all, "absolute and complete divorce

from your inkstand. . . . no letters to

strangers, or to any body else on politics."63

During the campaign, the President took

his own advice and stayed in

the background. Partisan electioneering

was then regarded beneath presi-

dential dignity. He did aid in every way

proper, even though he was gravely

disappointed at Garfield's equivocation

over civil service reform in his ac-

ceptance letter. Actually, direct aid

from Hayes was neither expected nor

desired in Garfield's camp.

After Garfield's election, Hayes still

had four months of his term left to

serve. He used this time to smooth the

transition of his successor to power.

So graciously was this clone that the

President-elect was moved to write, in

genuine gratitude, "I know of no

case, unless it may have been at the oc-

casion of Van Buren's when the transfer

of an administration was attended

with such cordiality of personal and

political friendship as in this case."64

Throughout the winter, Hayes obliged

Garfield by making appointments

at his request, while he, in turn,

suggested potential cabinet ministers for

Garfield's consideration. One of these,

William M. Hunt, an obscure south-

erner, otherwise unknown to the

President-elect, was chosen to be Secre-

tary of the Navy.

The transfer of power involved, also, a

mundane transfer of domestic

arrangements. Here Hayes was courtesy

itself. He invited Garfield and his

family to be his guests at the White

House until the inauguration and even

offered the use of his horses and

carriage. Garfield accepted tile hospitality

for his family, but he and his wife

decided to stay at a hotel in order to

save the outgoing President the

embarrassment of being ignored in his own

house while Garfield's friends (some of

whom, such as Blaine, were not

even on speaking terms with Hayes)

flocked to congratulate the incoming

Chief Executive.

The offer of the carriage team seemed

especially thoughtful. After a life-

time of public service, despite constant

accusations of corruption, Garfield

had never been able to afford this

luxury. But Hayes, apparently unable to

resist a good thing even at the expense

of his friend and successor, spoiled

the gesture by offering to sell the

horses. Garfield wisely consulted a veter-

inarian, who reported that Doc was lame,

Ben was blemished, and both

GARFIELD and HAYES

123

animals were worn out. "Whoever

buys them now," he warned, "is getting

the skim milk, the present owner has had

the cream."65 Garfield declined

the offer.

On the morning of March 1, the

President's son Webb met the Garfield

family at the Baltimore and Potomac

Depot and escorted the children and

their aged grandmother to the White

House. On the cold, rainy morning

of the fourth, the families of both

Presidents sat together on Capitol Hill

to watch the ceremonies. The Inaugural

Address, which promised to con-

tinue some of Hayes's foreign and

domestic policies, was hailed by the

former President as "in every way

sound and admirable."66 As the parade

began, the sun finally burst through the

clouds and Mrs. Hayes, always on

the alert for omens, exclaimed, "in

her enthusiastic manner," to Mrs. Gar-

field, "There! All is right now. I

have no more anxiety."67 Was her expres-

sion of relief for her successor, or for

herself safely done with public life at

last? One more luncheon to give, one

last receiving line, and then Mrs.

Hayes could leave the house where she

and her family had been on display

for four years.

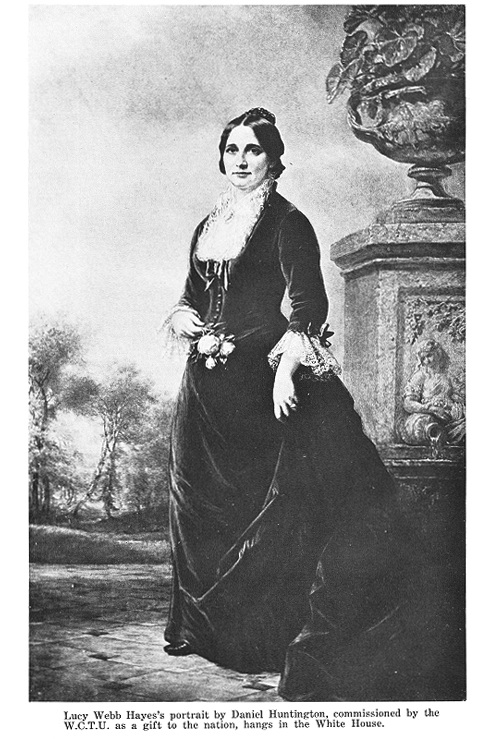

Yet, even after she had packed her bags

and returned to Fremont, the

spirit of Lucy Hayes still pervaded the

White House. Indeed, her presence

continued in the form of a portrait

commissioned by the Women's Chris-

tian Temperance Union which was

presented to the new President to re-

mind him of Mrs. Hayes's policy of

banishing wine from the White House

table. The practice had won her devotion

among temperance advocates

and a derisive nickname, "Lemonade

Lucy," from the scoffers. This was

the first crisis of the new

administration. For months, Hayes had pleaded

with Garfield to continue his emphasis

on temperance and ban alcohol. He

had even hinted that the restoration of

wine could defeat the Republican

party.68 James G. Blaine, on

the other hand, had urged Garfield to make

his administration a brilliant, social,

as well as political success. He sneered

at Mrs. Hayes for having "imported

into the White House the usages of

village society."69 Although

certainly no great drinker himself, Garfield

was inclined to agree with Blaine. He

accepted the portrait with thanks,

but pointedly reminded the temperance

delegation of "the absolute right

of each family to control its affairs in

accordance with the conscience and

convictions of duty of the heads of the

family."70 The portrait of Mrs.

Hayes was hung in the East Room next to

that of Martha Washington, and

wine flowed once more in the Executive

Mansion. Hayes was not pleased

with the innovation, but Presidents are

seldom completely satisfied with

the men who follow them.

In retirement Hayes busied himself with

good works, meanwhile keeping

eye on the doings of his successor. From

his vantage point at Spiegel Grove

in Ohio, he looked on the new

administration with sympathy mixed with

apprehension. Forgetting the difficulties

he had known as President, Hayes

attributed Garfield's problems to a lack

of executive experience. "I see more

clearly than ever," he observed in

April, ". . . that congressional life is

not the best introduction or preparation

for the President's house. Great,

124 OHIO HISTORY

and fully equipped as the general is,

there are embarrassments growing out

of his long and brilliant career which

Jackson and Lincoln, and Grant and

myself escaped. . . . But [he concluded

optimistically], I have confidence in

his purpose and hope for the

future."71

This hope, of course, was never

fulfilled. Only a few months later Gar-

field was assassinated, before he could

prove his fitness to be President.

Hayes fully shared in the deep stunned

grief the nation felt at the loss of

its leader. A few years later, however,

when emotions had subsided, Hayes

delivered a critical valedictory of

Garfield's career;

He was not executive in his talents, not

original, not firm--not a

moral force. He leaned on others--could

not face a frowning world; his

habits suffered from Washington life.

His course at various times when

trouble came betrayed weakness. The Credit

Mobilier affair, the De

Golyer business, his letter of

acceptance, and many times his vacilla-

tion when leading the House, place him

in another list from Lincoln,

Clay, Sumner, and other heroes of our

civil history.72

It was an uncharacteristically severe

judgment. Garfield deserved better

from Hayes. Yet Garfield had, after all,

said just as harsh things of Hayes

throughout the years. Neither man,

despite surface similarities, ever quite

understood or fully sympathized with the

other.

Nor has the judgment of time been kinder

to either of them. Both have

been assigned to the same gray

obscurity. Our age lacks sympathy with the

ponderous stuffiness of tile Gilded Age.

We prefer our political leaders to

have style and dash, to espouse positive

platforms and push for their en-

actment with vigor. Garfield and Hayes

held a more limited conception of

the uses of presidential power. Both

shared the prevailing laissez faire judg-

ment that the object of government was

to enforce the laws. They were not

weak leaders, but they had a limited

conception of the role of leadership

and they stayed within that framework.

Too often, the politics of the post

Civil War period is treated as if it

were solely a record of crassness and

corruption. Yet in Garfield and Hayes

we find leaders who possessed essential

integrity and considerable intellec-

tual strength.

Garfield liked to cite a phrase of

George Canning: "My road must be

through character to power." In a

way, the motto could apply to both Gar-

field and Hayes whose careers

demonstrated that not all that glittered in

the Gilded Age was gilt.

THE AUTHOR: Allan Peskin is As-

sociate Professor of History at

Cleveland

State University.