Ohio History Journal

ROBERT M. MENNEL

"The Family System

of Common

Farmers": The Origins

of

Ohio's Reform Farm, 1840-1858

The early history of the Ohio Reform

School for Boys,1 which

opened in 1858, provides a unique

opportunity to analyze the de-

velopment of attitudes and policies

toward juvenile delinquency and

related problems such as dependency and

neglect-all major

concerns of nineteenth century society.

As the first American

institution to combine a decentralized

family or cottage building

plan with an agricultural work routine,

the school significantly

influenced reform school construction

and administration in other

states. And because it was organized

with reference to similar

work in western Europe, the Reform Farm

can enlarge our under-

standing in a comparative sense. By

highlighting the assumptions

and work of Americans, particularly

their faith in the virtues

imparted by agrarian family life, the

comparative approach allows

one to connect the institution's history

to broader social, economic,

cultural, and political forces.

Prologue: The Cincinnati House of

Refuge

Efforts to define and control

delinquency in Ohio originated

in the late 1830s among a local elite in

Cincinnati, by far the

Robert M. Mennel is Professor of History

at the University of New

Hampshire. He wishes to thank the

American Philosophical Society, the

Charles Warren Center for Studies in

American History, and the Central

University Research Fund of the

University of New Hampshire for research

support in the preparation of this

article.

1. In 1884, the institution was renamed

the Boys' Industrial School;

its present name, The Fairfield School

for Boys, dates from 1964. Through-

out the later nineteenth century and indeed well into

the twentieth it was

commonly known as the State Farm or the

Reform Farm.

126 OHIO HISTORY

state's largest city.2 This group may be

usefully described as

white males in their forties, Protestant

moralists, Yankee migrants,

Whigs (later Republicans), and

businessmen or professionals (law,

journalism, or education, often pursued

simultaneously). Notable

among them were Alphonso Taft, Samuel

Lewis, and James

Handasyd Perkins.3 They

opposed slavery and enthusiastically

supported a variety of good works,

including popular education

and the systematic organization of poor

relief and penal institu-

tions.4 It is fruitful to

examine the Cincinnati House of Refuge,

the product of one of their benevolent

campaigns, because its

claims for state aid and its development

as an institution signifi-

cantly shaped the history of the State

Farm.

2. In 1840, Cincinnati's population

(46,000) comprised over half of the

population in the state residing in urban places (over

2,500 residents). By

1850, Cincinnati had grown to 115,000,

nearly seven times the size of its

nearest rivals, Columbus and Cleveland

(both c. 17,000).

3. Alphonso Taft, Secretary of War in

the Grant administration and

father of the President, was born in

Vermont. He received his law degree

from Yale (1833) and migrated from

Connecticut in 1840 to become one of

Cincinnati's most successful lawyers.

Samuel Lewis, in 1814 an impoverished

migrant from Massachusetts, gained

affluence through marriage and as a

legal adviser to local businessmen. In

1838 he was appointed the first State

Superintendent of Common Schools.

Militantly antislavery, he helped Salmon

P. Chase, another Yankee-born Cincinnati

lawyer, organize the Liberty

Party. Later, Lewis was an unsuccessful

Free Soil candidate for Congress

and the governorship. James Handasyd

Perkins left a comfortable family

import business in Boston to become a

lawyer-journalist in Cincinnati in

1832. He subsequently accepted a call

from the First Congregational Society,

but the relationship was strained as

Perkins goaded the pious membership

to get involved in practical work such

as the Cincinnati Relief Union which

he helped to establish. See Henry F.

Pringle, The Life and Times of William

Howard Taft, I (New York, 1939), 7-19; W. G. W. Lewis, Biography

of

Samuel Lewis (Cincinnati, 1857); William H. Channing, ed., Memoirs

and

Writings of James Handasyd Perkins, 2 vols. (Cincinnati, 1851).

4. The following facts help to place

this group within the state's and

the city's population. DeBow's 1850

Census divides the nativity of Ohio's

white population (1,955,050) into three

parts: Ohio born (62 percent);

born in other states (27 percent);

foreign born (11 percent). Natives of

the New England states totaled 65,000

or, approximately 3 percent of the

total population, 6 percent of the Ohio

born population, 12 percent of the

population migrating from other states

and 30 percent of the foreign-born

population. Half of the foreign-born

population was from Germany. Even

within Cincinnati, New England migrants

were a distinct minority. Charles

Cist's 1841 survey of the adult (over

20) white male population shows them

comprising 8 percent of the total and 15

percent of the native-born popula-

tion. J. D. B. DeBow, Statistical

View of the United States . . . Being a

Compendium of the Seventh Census .... (Washington, D.C., 1854), 61, 63,

116-18; Charles Cist, Cincinnati in

1841: Its Early Annals and Future

Prospects (Cincinnati, 1841), 38-39.

Family System of Common Farmers 127

The Cincinnatians approached the

problem of delinquency in

the paternalistic manner that they

believed characterized their

colonial ancestors. James Perkins

explicitly likened his colleagues

to New England "select men"

whose duty it was "to go out into

the highways and hedges of society and

compel all the vagrant

children to come in."5 Seeking

contemporary examples of this

exercise of power, Perkins led a

delegation that visited houses of

refuge and other homes for dependent

and delinquent children in

eastern cities. These institutions had

been founded in the 1820s

and 1830s by local elites who were

concerned about the presence

of children in the jails and

penitentiaries as well as the growing

numbers of orphaned or neglected young

people who wandered

the streets at all hours.6

By 1840, the houses of refuge had

evolved into juvenile models

of adult penitentiaries and confined

principally children who had

been convicted of petit larceny or

repeated vagrancy. The Cincin-

natians believed that their city could

use a similar institution, but

they were also impressed by a visit

they took to Thompson's Island

in Boston harbor where a group of

reformers had established in

1833 a manual labor and farm school for

boys between the ages

of seven and fourteen who were vagrant

but had not been con-

victed of other offenses. The head of

this school, E. M. P. Wells,

operated a system of control based upon

moral suasion and peer

group pressure, requiring, for example,

the boys to grade each

other's conduct. Days were divided into

periods of farm and

mechanical labor interspersed with

instruction in "elementary

knowledge."7

5. In southern states, Perkins

contended, this authority was not re-

quired because "disease generally

relieves the public of so many of this

class of children." Quoted in John

P. Foote, The Schools of Cincinnati and

Its Vicinity (Cincinnati, 1851), 116-17.

6. On the origins of the houses of

refuge see Robert M. Mennel,

Thorns and Thistles: Juvenile

Delinquents in the United States, 1825-1940

(Hanover, New Hampshire, 1973); Robert

S. Pickett, House of Refuge:

Origins of Juvenile Reform in New

York State, 1815-1857 (Syracuse,

1969);

David Rothman, The Discovery of the

Asylum: Social Order and Disorder

in the New Republic (Boston, 1971); Steven L. Schlossman, Love and the

American Delinquent: The Theory and

Practice of Progressive Juvenile

Justice, 1825-1920 (Chicago, 1977).

7. Foote, The Schools of Cincinnati, 119-21.

Founders of Thompson's

Island included the Pestalozzian

educator and journalist William Channing

Woodbridge and the Unitarian clergyman

Joseph Tuckerman whose minis-

try to the poor undoubtedly inspired

James Perkins. E. M. P. Wells had

earlier been fired as Superintendent of

the Boston House of Reformation

when he resisted the implementation of

contract labor and refused to apply

128 OHIO HISTORY

Upon returning to Cincinnati, James

Perkins submitted a

report to the City Council, calling for

"schools of moral reform

for the vicious," such as

Thompson's Island, and "houses of refuge

for the criminal." The refuge

would contain not only youths con-

victed of serious offenses, but also

children who failed to behave

at the moral reform school.8 Thus,

the Cincinnati reformers

envisioned a double-tiered

institutional response, increasingly

severe as individual behavior dictated.

In the early 1840s the Perkins report

was discussed in City

Council and at public meetings. While

there was little opposition

to the general goals of the proposed

institutions, action was delayed

by the necessity of obtaining a state

charter and by confusion

regarding financing and control. In

1844, the Council asked David

T. Disney, the local (Hamilton County)

state senator, to introduce

a bill requesting state authority and

financial aid to build two

juvenile institutions. A house of

correction would confine males

over sixteen as well as females over

fourteen who had been

sentenced to the county jail or

committed for trial or were being

held as witnesses. A house of

reformation would confine younger

youths of both sexes who had been

sentenced to the local jail. At

the discretion of the sentencing

magistrate, children destined for

the state penitentiary could also be

sent to the house of reforma-

tion.9

The state legislature was lavish in its

praise of the proposed

institutions but unwilling to provide

financial assistance despite

Disney's effort to broaden the bill's

appeal by adding houses of

reformation for Cleveland and Columbus

and funding all institu-

tions with "surplus revenue

derived from the State penitentiary."

In fact, the amendment was probably

counterproductive because

it threatened a cherished source of

legislative self-aggrandizement.

As finally passed, the bill allowed

Cincinnati to build one institution,

a house of refuge, but only when one

hundred citizens subscribed

"either fifty dollars for life

membership, or five dollars yearly."10

corporal punishment liberally. See

Mennel, Thorns and Thistles, 25-26

and Robert H. Bremner, ed., Children

and Youth in America, I (Cambridge,

Massachusetts, 1970), 726-29.

8. Foote, The Schools of Cincinnati, 119-21.

9. Alphonso Taft, Address Delivered

on the Occasion of the Opening

of the Cincinnati House of Refuge (Cincinnati, 1851), 24-25; Ohio. Senate

Journal (1844-45), 555-57. On Disney, see Charles Cist, Sketches

and

Statistics of Cincinnati in 1851 (Cincinnati,

1851), 289-91.

10. Ohio. Senate Journal (1844-45),

556-57, 575; Ohio. Laws, XLIII

Family System of Common Farmers 129

The Cincinnati reformers, however, had

difficulty obtaining

subscriptions and had to rely largely

upon municipal funds for

construction. Their dependence

partially explains the legislature's

revision of the enabling act in 1847,

allowing the City Council a

majority of the institution's Board of

Managers. At the opening

ceremonies in 1850, Alphonso Taft

pointedly reminded his audience

of "$600 of subscriptions now due

and unpaid." Yet, Cincinnatians

did not draw fine distinctions between

public and quasi-public in-

stitutions. They believed that the

Refuge served the public and

were prepared to use their political

influence to block any further

state anti-delinquency program which

did not financially aid their

own institution. In 1856, the Refuge

directors warned:

The pecuniary burthen of this work has

... fallen entirely and heavily

on the citizens of Cincinnati, and we believe their

Institution is the only

one of the kind in the Union sustained

without the aid of state contribu-

tion; but this state of things will not,

we trust, be permitted to continue.

The General Assembly, recognizing as the

children of the State all

within its borders, will, doubtless, find

it consistent with the philan-

thropy of the people of the State to aid

our Institution . . .11

Despite James Perkins' hope that

Cincinnati would build a

replica of the Thompson's Island farm

school, the completed

building-a large stone edifice surrounded

by high walls-

physically resembled the older and more

explicitly penal houses

of refuge. The internal routine was

also similar. Common schooling

was provided, but the founders' initial

determination to avoid con-

tract labor soon gave way to the

stronger imperative that children

should earn part of their keep and that

repetitive labor tasks

were excellent inculcators of sobriety

and regular habits. As in

the eastern institutions, a small

number of girls, most of whom

had been charged with morals offenses,

were admitted. They

(1844-45), 393-95; Ohio. Report on

the Debates and Proceedings of the

Convention for the Revision of the

Constitution, 1850-51, I (Columbus,

1851), 539-49, II, 340-44. Throughout

the nineteenth century the penitentiary

maintained an abusive and corrupt

reputation by confining youths with

older criminals and by leasing convicts

at low cost to politically influential

manufacturers. See John Phillips Resch,

"The Ohio Adult Penal System,

1850-1900: A Case Study in the Failure

of Institutional Reform," Ohio

History, LXXXI (Autumn, 1972). 236-62.

11. Ohio. Laws, XLV (1846-47),

112-13; Alphonso Taft, Address . . .

Cincinnati Refuge, 9; Cincinnati House of Refuge, Annual Report (AR)

(1856), 9. This attitude was probably

fortified by their difficult experience

collecting from the state for damages

suffered when the Miami Canal over-

flowed into the institution. See

Cincinnati Refuge, AR (1852), 6-7.

130 OHIO HISTORY

were assigned the institution's

housework but were regarded as a

distraction to the principal task of

reforming boys. By 1856, the

all-male board of directors was seeking

funds for a female refuge

"separate and entirely

disconnected" from the rest of the institu-

tion.12

The principal difference between the

Cincinnati Refuge and

its east coast counterparts lay in the

Ohioans' broader social defini-

tion of delinquency. Eastern and

western reformers agreed that

parental indifference and

permissiveness were the primary rea-

sons for the increase in juvenile

delinquency, but Cincinnatians

defined "parental folly and

disorder" as a pathology potentially

applicable to rich and poor families

alike and, hence, viewed juve-

nile delinquency as a broader menace to

secondary social institu-

tions, particularly the schools.13 "Through the truants," James

Perkins warned, "evil knowledge

and evil practices come into the

little kingdom of the schools."

True, Perkins singled out teenage

"river-boys" living in the

city's basin district as the most likely

candidates for the institution. But

Alphonso Taft specifically

noted "the profligacy of the

youthful expectants of patrimonial

estates . . . that numerous and well

known race of "third genera-

tion' men," as a principal reason

for building the refuge.14

Time would prove Perkins correct, but

the important point

for the 1850s was the Cincinnatians'

shared belief that they had

identified and begun to solve a

critical social problem that other

parts of the state would soon face.

Alphonso Taft warned:

12. Cincinnati Refuge, AR (1851), 15-16;

Ibid. (1857), 7-8; Ibid.

(1858), 5; Ibid. (1852), 12-13; Ibid.

(1856), 7-10. It is important to re-

member that Ohioans of the 1840s did not

view the first houses of refuge

in the negative manner of subsequent

generations. State legislators, for

example, praised houses of refuge as

"well regulated christian [sic] com-

munities and families," thus

suggesting that, in their minds, there was no

necessary opposition between the

discipline of the institutions and the

characteristics of family life. See,

Ohio. Senate Journal (1844-45), 556-57,

575.

13. On the propensity of eastern elites

to see houses of refuge and

common schools as necessities for

children other than their own, see Mennel,

Thorns and Thistles, chapter one; Carl Kaestle, The Evolution of an Urban

School System: New York City,

1750-1850 (Cambridge, Massachusetts,

1973).

14. Foote, The Schools of Cincinnati,

119-20; Taft, Address, 12;

Cincinnati Refuge, AR (1851), 24. There

is more than a tinge of worry in

a letter from Taft to his second wife,

Louise Torrey, thanking her for

raising the two sons of his first

marriage and teaching them "propriety

and manners." See Pringle, The

Life and Times of William Howard Taft, 13.

Family System of Common Farmers 131

Next to the reformation of the children

of our own city, we are in-

terested in that of the delinquent

youths of our neighbors.-Rogues, like

wild beasts of prey, are never

stationary. Their home may be said to be

among strangers. From city to city they

roam, and are ever most suc-

cessful where they are least known.15

Also, by describing juvenile

delinquency as a problem common

to all social classes and as a threat

to popular institutions, Cincin-

nati reformers illustrated a new

rhetoric of social control that

catered to the egalitarianism of the

age. How this philosophy was

disseminated throughout the state is of

major importance.

Charles Reemelin and the Beginnings

of a State Program

With the opening of the Cincinnati

Refuge in 1850, debate

on the need for a state institution for

juvenile delinquents temp-

orarily receded to the level of a

perfunctory paragraph in the

Governor's annual message. In 1851

Seabury Ford (Whig) recom-

mended a state institution similar to

the Massachusetts Reform

School at Westboro (1847) where the

boys were "contented, happy

and ambitious." The following year

Reuben Wood (Democrat)

proposed state aid to encourage

municipalities to build houses of

refuge similar to the Cincinnati

institution. In neither case did

the legislature take any action.16

Several factors, however, encouraged

the possibility of state

action. First, the state was continuing

to grow in population in

the 1850s, especially in its urban

sector where delinquency was one

of the characteristics of growth. The

state as a whole increased

by 400,000 in the decade, with cities

and towns over 2,500 absorbing

most of the addition. Cleveland more

than doubled its population,

rising from 17,000 to 43,000; Dayton

increased from 10,000 to

20,000; Toledo from 4,000 to 13,000.

Newark in Licking County

grew from 3,600 to 4,600 while the

county population as a whole

declined. In 1850 there were eleven

counties with populations of

less than 10,000; in 1860 there were

three.17 Second, as evidenced

by the legislative debate over aid to

the Cincinnati Refuge, there

was wide support for the idea of

separate institutions for juvenile

15. Taft, Address, 24-25.

16. Ohio. Executive Documents (1851),

13-14; (1852), 16. For a sum-

mary of legislation affecting delinquent

children in nineteenth century

Ohio see Nelson L. Bossing,

"History of Educational Legislation, 1851 to

1925," Ohio Archeological and

Historical Publications, XXXIX (1930),

291-300.

17. In subsequent work, I shall discuss

further the relationship between

132 OHIO HISTORY

delinquents. In 1854 several state

representatives, after visiting

some of the younger inmates at the

state penitentiary, proposed

that the state build an institution

similar to the New York House

of Refuge. Their effort, though

unsuccessful, indicated that a

reform school program, by diverting the

flow of youths to the

penitentiary and by offering services

to the entire state, might

succeed. Finally, with the creation of

the State Teachers Associ-

ation (1847), an educators' lobby began

to promote a state reform

school. Local school boards such as

Cleveland's augmented this

pressure with demands for refuges and

industrial schools to con-

trol truants and school yard idlers.18

Salmon P. Chase was the catalyst.

Beginning in 1830, he had

practiced law in Cincinnati. Though he

shared the New England

origins of the founders of the

Cincinnati Refuge, he was not active

in the campaign to build the

institution, concentrating instead on

defense of runaway slaves. Ousted from

the U.S. Senate in 1854,

he returned to Ohio to build an

"anti-Nebraska" party as a spring-

board for his later campaigns for the

Presidency. In 1855 Chase

stitched together an unstable coalition

of independent Democrats

(many of whom were Germans),

Free-Soilers, abolitionists, Know-

Nothings, and "conscience"

Whigs to win the Governorship by

15,000 votes.19 In his

inaugural address Chase asked the legisla-

delinquency and urbanization. I refer

here not to the rate of criminal or

disruptive behavior by youths of any

particular place but rather to the

likelihood that such behavior would lead

to the reform school. In 1860

half of the new inmates at the Farm came

from the five largest counties

(Hamilton, Cuyahoga, Franklin,

Montgomery, and Muskingum) which to-

gether accounted for less than 19

percent of the state's population. Because

the Cincinnati Refuge absorbed many of Hamilton

County's delinquents,

this jurisdiction, containing 10 percent

of the state's population, contributed

only 3 percent of the new inmates.

Cuyahoga County (Cleveland), with

only 3 percent of the state's

population, contributed 31 percent of the

admittees.

18. American Journal of Education, VI

(1859), 532-54; Ohio. Docs.,

II (1891), 1023; Cleveland Board of

Education, AR (1854-55), 19-23; Ibid.

(1855-56), 16-17. Early industrial

schools did not teach trades but rather

employed children in menial tasks (rag

picking, etc.), fed them, and pro-

vided some elementary education. Most

operated during the day only.

19. Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon

Portland Chase (Boston, 1899), 132-

33, 150-58. See also Jacob W. Schukers, The

Life and Public Services of

Salmon Portland Chase (New York, 1874); Robert B. Warden, An Account

of the Private Life and Public

Services of Salmon Portland Chase (Cin-

cinnati, 1874); Dictionary of

American Biography, IV (1930), 27-34. The

difficulty of maintaining friendly

relations between these factions cannot

be understated. Chase simultaneously

enjoyed the confidence of Quakers,

Family System of Common Farmers 133

ture to extend the "benefits"

of benevolent institutions "to all,

without distinction, who need their

care." The legislature, though

opposed to opening state institutions

to the miniscule free black

population, was willing to consider the

extension of institutions,

such as reform schools, to whites.20

The backbone of Chase's legislative

support lay in the Western

Reserve among fellow New England

migrants who admired his

long-standing opposition to fugitive

slave laws. One of the leaders

of this group was James Monroe, a young

Oberlin professor of

rhetoric and belles lettres who was

elected state representative

in 1856. Monroe introduced a bill to

establish "the Ohio House of

Refuge" to be located "at a

distance of not less than two miles

from the city of Columbus." He

chose Columbus to conform to

precedent: the penitentiary, deaf and

dumb asylum, and the blind

asylum were already located there.

Because various legislators

from other localities objected, the

final bill left the selection of

site and architect to three

Commissioners "appointed by the

Governor by and with the advice of the

Senate."21

The first reform school bill was

distinguished by tones of

parsimony and calculated vagueness. The

Commissioners were

provided with an appropriation of

$1,000 plus travel and living

expenses when engaged in their duties.

With this sum, they were

to hire "a competent architect"

and visit three other reform

schools in the United States. They were

to furnish the legislature

with "full and exact"

information regarding building costs and

German-Americans and, even though they

had their own candidate in 1855,

some Know-Nothings. "My sin is

my Americanism," wrote one man. A

Quaker warned him that friendship with

Know-Nothings would subvert the

antislavery principles upon which the

Republican Party was forming. See

L. D. Campbell to Chase, February 9,

1856, and Alexander S. Latty to

Chase, December 18, 1855, Box 28, The

Papers of Salmon P. Chase, Liberty

of Congress (LC). See also, Roeliff

Brinkerhoff, Recollections of a Life-

time (Cincinnati, 1900); Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free

Labor, Free Men:

The Ideology of the Republican Party

before the Civil War (New York,

1970), 244-45.

20. Salmon P. Chase, Inaugural

Address (Columbus ,1856), 4. On

the exclusion of blacks from state

services, see David A. Gerber, Black

Ohio and the Color Line, 1860-1915 (Urbana, Illinois, 1976), 4-6.

21. W. H. Phillips, Oberlin Colony:

The Story of a Century (Oberlin,

1933), 203-17; Robert S. Fletcher, A

History of Oberlin, I (Oberlin, 1943),

390-414; Ohio. House Journal (1856),

414, 487, 567; Ohio. Laws, LIII

(1856), 66-67; James Monroe, Oberlin

Thursday Lectures, Addresses and

Essays (Oberlin, 1897), 121-25. Monroe's own scheme for an

institution

specified that the boys "might have

firecrackers on the 4th of July, a turkey

for Thanksgiving, a plum pudding at

Christmas, and nuts and apples on

New Year's."

134 OHIO HISTORY

admonished to "make no contract in

anticipation of appropriations"

unless they wished to be "held

responsible in their private capa-

cities." The vagueness stemmed

from the need to pacify Hamilton

County (Cincinnati) representatives.

Thus, the possibility of a

state subsidy for the Cincinnati Refuge

remained and, by opening

the institution to "persons not

exceeding twenty years of age,"

(i.e., not specifying the sex of

inmates) the bill enticed Cincin-

natians with the prospect of ridding

their institution of female

delinquents.22

The bill was widely supported, passing

the house 75-10 and

the senate 26-3. The thirteen senators

and representatives voting

against the reform school included six

farmers, two physicians, two

lawyers, two skilled workers, and one

merchant. Only two came

from rapidly growing counties (Stark

and Lawrence); the balance

came from areas that had yet to grow

substantially or else were

actually losing population. Unlike the

legislators and citizens who

advocated institutions, ten of the

thirteen politicians had lived in

Ohio all their lives.23 The

point here is that opposition to the

reform school was insubstantial and

unorganized although the

institution symbolized a significant

shift toward a more active

welfare state in Ohio. Adopted after

perfunctory debate, the

Reform Farm demonstrates that the

casually agreed-upon law can

epitomize social and political change

of a fundamental and un-

anticipated nature.

Salmon Chase moved quickly to appoint

the Commissioners in

order to forestall self-promoters and

lobbyists for other indivi-

duals and to take advantage of an

opportunity to increase the

slender powers of the Governorship.24

His appointments reflected

the coalition that elected him. James

D. Ladd, a Quaker pacifist

from Steubenville, was active in the

underground railroad in

eastern Ohio.25 John A.

Foot, son of Connecticut Governor and

U. S. Senator Samuel A. Foot, graduated

from Yale law school

and migrated to Cleveland in 1833 at

the age of thirty. He vigor-

ously promoted railroads and public

education and helped to

22. Ohio. Laws, LIII (1856),

66-67; Ohio. Senate Journal (1856),

375, 382. See also Monroe, Thursday

Lectures, 123.

23. Ohio, House Journal (1856),

414-15 and, appendix, 104-09; Senate

Journal (1856), 382-83.

24. Box 2, Folder 6, The Papers of

Salmon P. Chase, Ohio Historical

Society; Hart, Chase, 150-58.

25. Edward S. Ebbert comp., Lancaster

and Fairfield County (Lan-

caster, Ohio, 1901), 63-72; Henry M.

Wynkoop, comp., Picturesque Lan-

caster (Lancaster, Ohio, 1897), 22-23.

Family System of Common Farmers 135

establish the Cuyahoga Anti-Slavery

Society.26 The dominant

figure in the early history of the

reform school was Charles

Reemelin, whose early life and career

deserve particular attention.

Reemelin was born Carl Gustav Rumelin

in the free city of

Heilbronn (Wurttemberg, Germany) in

1814. His father was a

prosperous wholesale grocer; his mother

came from a well-to-do

family. Family life was encompassing

and satisfying to the young

boy. Later he remembered:

It was the outer world, the outside

eventualities that marred our general

home happiness; for on our visits to

relations, we found there only evi-

dences of ... the inherent superiority

of our kind of social life. And this

confirmed in us that thing called:

family pride. We attributed the good

we enjoyed to our parents and to their

ancestors on both sides; for we

knew of no evil they had ever caused

either to ourselves or any body else.

This harmony was shattered in the 1820s

as the child witnessed

his parents fighting and as they both

began to withdraw from his

life-his father to the world of

business, his mother to a sani-

tarium where she died in 1823.27

Reemelin's unhappiness deepened when

his father remarried

in 1826. Soon thereafter his father

forced him to enter the family

business and he ran away. Upon being

apprehended, he was

apprenticed as a cadet at Denkendorf

(literally Thinking Village),

an experimental beet sugar factory established

by the King of

Prussia. Here he developed what would

be a lifelong interest in

horticulture and learned the arts of

evaporation and fermentation.

Paradoxically, he also became

disenchanted with life in Germany

because of what he regarded as the

excessive interference of the

state in economic matters. As a clerk

in a Wimpfen (Hesse-

Darmstadt) grocery, he spent most of

his time arranging smug-

gling deals to evade the complicated

tariff barriers of the various

German states and duchies. Inspired by

Gottfried Duden's letters

26. Elroy M. Avery, A History of

Cleveland and Its Environs: The

Heart of New Connecticut, I (Chicago, 1918), 151, 208, 217, 345; W. Scott

Robinson, ed., History of the City of

Cleveland (Cleveland, 1887), ap-

pendix, x; James Harrison Kennedy, A

History of the City of Cleveland

(Cleveland, 1896), 251-52. See also

Nathaniel Goodwin, The Foote Family

(Hartford, 1849), 245-46, 649, 651. John

A. Foot was distantly related to

the Cincinnati journalist-reformers John

P. Foote and Samuel E. Foote.

See above, In, 2n.

27. Charles Reemelin, Life of Charles

Reemelin (Cincinnati, 1892),

1-7.

136 OHIO HISTORY

from America and finally freed by his

father, Carl Rumelin sailed

for Philadelphia in the summer of

1832.28

In America he epitomized the vital and

eclectic spirit of the

age. He worked briefly in an Irish

Grocery store in Philadelphia,

and also became a Jacksonian because of

the Democratic leader's

advocacy of free trade and hard money.

In 1833 he moved to

Cincinnati and began to prosper as a

grocer and as founder and

editor of the Volksblatt. Reemelin

married in 1837 and later

moved his growing family to a farm in

suburban Dent where he

planted an orchard and a vineyard,

becoming particularly expert

in methods of wine culture. In the 1840s

he visited Europe twice,

once serving as a correspondent for

William Cullen Bryant's New

York Evening Post. He referred to

himself as "a practical vint-

ner" or as a farmer, but by 1855 he

was President of the Cincin-

nati and Dayton Short Line Rail Road and

deeply immersed in

the problems of raising capital.29

Charles Reemelin's political career

began in 1844 with election

to the state house of representatives.

Two years later he was

elected to the state senate and, in

1850, he became a delegate to

the State Constitutional Convention. In

all these posts he demon-

strated a prickly independence that

ultimately circumscribed his

career within the state Democratic

party. At the Constitutional

Convention, he triumphed in his campaign

to outlaw the legislative

gerrymander but was decisively and

derisively defeated in his

efforts to strengthen the governorship

and to allow penitentiary

inmates to keep their earnings.30

Reemelin idealized the German

bureaucracy. For him, a

virtuous state was a function of a

powerful, expert, and independent

civil service which would infuse

government with efficiency as well

as moral and social purpose. Reemelin

saw no contradiction be-

tween this belief and his faith in

Jacksonian democracy because,

in German metaphysical fashion, he

believed that popular will

reflected perfect or Absolute will. The

mark of an able civil

28. Reemelin, Life, 8-19; Henry

A. Ford and Kate B. Ford, comps.,

History of Cincinnati, Ohio with

Illustrations and Biographical Sketches

(Cincinnati, 1881), 130-32; Gottfried

Duden, Bericht uber eine Reise nach

den westlichen Staaten Nordamerikas .

. . (Elberfeld, 1829).

29. Ford and Ford, Cincinnati, 130-31;

Saxton's Rural Handbooks:

Third Series (New York, 1856), 7, 103. "May God bless the

vintner's skill and

toil!" concluded Reemelin. See

also, Ohio. State Board of Agriculture, AR

(1870), 542-55; Charles Reemelin, The

Vine-dresser's Manual (New York,

1857).

30. Ford and Ford, Cincinnati, 131;

Ohio. Proceedings of the [Con-

stitutional] Convention (1851), II, 340-44; Ibid., I, 697-704.

|

Family System of Common Farmers 137 |

|

|

|

servant was recognition of this fact. Outraged by the American spoils system, Reemelin constantly sought politicians in rebellion against established party organization in the hope that they would share his vision of the state. For this reason and because of the abuse which he suffered from Know-Nothings within the Demo- cratic Party, he gained favor with Salmon P. Chase by muting his support of Governor William Medill, who was running for reelec- tion. Following Reemelin's appointment as Reform School Com- missioner, he wrote Chase urging a "radical reformation" of "the General and States Government." Reemelin's quest for a harmon- ious political science eventually led him to quote Calhoun and, in 1860, to endorse Breckinridge; in the meantime, he was a mainstay of Chase's efforts to hold the support of German-Americans.31

31. Charles Reemelin, Treatise on Politics as a Science (Cincinnati, 1875), 44, 181-82; Reemelin, Life, 128-29, 155-56; Reemelin to Chase, April 29, 1856, container 29, Chase MS, LC. See also Charles Reemelin, A Critical Review of American Politics (Cincinnati, 1881) and Clifton K. Yearley, The Money Machines; the Breakdown and Reform of Govern- mental and Party Finance in the North, 1860-1920 (Albany, 1970), 32-33. One of Chase's confidants suggested Reemelin for Lieutenant Governor in 1857 because "outside of the Reserve we are in a minority .... ." James M. Ashley to Chase, November 27, 1856, container 30, Chase MS, LC. |

138 OHIO HISTORY

The Reform School Commissioners met for

the first time on

April 18, 1856. Foot was elected

Chairman and Ladd, Secretary.

Reemelin, however, assumed the dominant

role. Since he was

about to visit Europe to settle his

father's estate and to find

bankers willing to market Dayton Short

Line bonds, he volunteered

to visit European reform schools and

report his findings. Prior

to his departure, the Commissioners

toured reform schools,

refuges, and industrial schools in the

eastern states. Their journal

of this period is perfunctory: Westboro

was "a model institution";

the New York House of Refuge was

"prominent." Reemelin was

not impressed: "None of these

institutions suited me fully. I

wanted one, that was in no way a prison,

except for temporary

punishment."32

The Commissioners undertook their

mission nearly devoid

of knowledge of existing reformatory

programs in either Europe

or America. They referred to Charles

Loring Brace's newsboys'

lodging house in New York as "Mr.

Braus' School for Vagrant

Boys" and seemed unaware of the

bitter dispute between Brace,

who advocated immediate placing out,

and the New York in-

stitution managers who favored lengthy

incarceration. Nor did

they seem informed of the extensive

literature on foreign reform

schools. Beginning in the first American

Journal of Education

(1826), articles describing these

institutions appeared regularly

in pedagogical publications. Calvin

Stowe's Report on Ele-

mentary Public Instruction in

Europe, containing a perceptive

discussion of Johann H. Wichern's Rauhe

Haus (Hamburg), was

originally a report made to the Ohio

legislature in 1837. And

an early issue of Henry Barnard's American

Journal of Educa-

tion (1855) promoted European cottage reform schools as

pre-

ferable to the American houses of

refuge.33

32. Ohio. Docs., I (1856),

626-27; Reemelin, Life, 131-34. Another

purpose of Reemelin's journey was to

persuade the famous German ex-

plorer Alexander von Humboldt to endorse

the Republican Presidential

nominee John Fremont. Humboldt refused.

The Commission's journal also

records that the trip would be

"without expense to the State." Reemelin

believed that Chase had promised him

reimbursement.

33. Calvin E. Stowe, Report on

Elementary Public Instruction in

Europe (Boston, 1838); American Annals of Education, I

(1830), 341-54;

Ibid. (1838), 112; Common School Journal, III (1841),

154-58; American

Journal of Education, I (1855), 611-39. See also Alexander Dallas Bache,

Education in Europe (Philadelphia, 1839); Horace Mann, Report of an

Educational Tour in Germany, and

Parts of Great Britain and Ireland

(London, 1846); Henry Barnard, National

Education in Europe (Hart-

ford, 1854).

Family System of Common Farmers 139

Of all this Reemelin was ignorant when

he left for Europe

in July, 1856. His first stop was Red Hill, an

agricultural reform

school located in Surrey, England, and

operated by the Royal

Philanthropic Society (London). Again

he was disappointed-

"much ceremonious praying and

stiff piety.... Personal clean-

liness and good manners were neglected,

and so were habits of

economy and propriety, the proper

handling of tools and nice

behavior in the rooms and on the

playgrounds." Though the

rural setting gave "the appearance

of kindliness and freedom,"

Reemelin believed that instruction

through the "comforts and

enjoyments" of life was ignored.

Citing Plato, he said, "True

education means improvement of the body

through gymnastics,

as of the soul through music."34

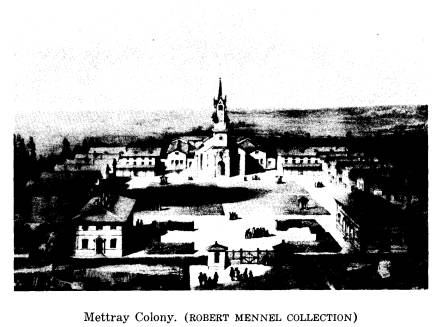

Sydney Turner, the Angelican cleric who

was Red Hill's

superintendent, had moved the

institution from St. George's field

in London to the country after

observing Mettray, a French

agricultural colony established in 1839

by Frederic Auguste De-

Metz, a penal reformer and lawyer at

the French Royal Court.

Mettray was organized on the cottage

plan, with boys living forty

to a dormitory under the supervision of

"elder brothers," young

men specially chosen by DeMetz and

trained at the institution's

Ecole Preparatoire. The boys spent several hours each day in

the classroom, but most of the time

they worked; some were

employed in trades or in the orchards

and vineyards but the

majority performed hard agricultural

labor-digging and crushing

stones for roads, draining low lands,

and subsoiling grain fields.35

DeMetz's work attracted favorable

notice in England from

the outset, but following passage of

the first Youthful Offenders

Act (1854), which greatly stimulated

the building of reform and

industrial schools, he became the vogue

of the British philan-

thropic world. In May 1856, he

addressed the National Reforma-

34. Reemelin, Life, 135. On the

reform school movement in England

see Lionel W. Fox, The English Prison

and Borstal Systems (London,

1952); Ivy Pinchbeck and Margaret

Hewitt, Children in English Society,

vol. I (London, 1969); Julius Carlebach,

Caring for Children in Trouble

(London, 1970); Margaret May,

"Innocence and Experience: The Evolution

of the Concept of Juvenile Delinquency

in the Mid-Nineteenth Century,"

Victorian Studies, XVII (September, 1973), 7-30.

35. Sydney Turner and Thomas Paynter, Report

on the System and

Arrangements of "La Colonie

Agricole" At Mettray (London,

1846);

"Mettray: Its Rise and

Progress," Irish Quarterly Review, VI (December

1856), 915-82; Notice sur L'Ecole

Preparatoire annexee a la Colonie de

Mettray (Paris, 1860).

140 OHIO HISTORY

tory Union and was elected an honorary

member. Mettray was

hailed as "the Mecca of the

Reformatory School."36

Reemelin agreed. After a short visit,

he pronounced Mettray

"the best Reform School in the

world . . . the model for us in the

United States, to follow."37 Reemelin

was fascinated by the

supervisory advantages provided by

cottages and the relationship

between institutional development and

the farm economy. The

cottage system offered the

superintendent "the opportunity to com-

pare the movements of his under officers

. .. negligence or relaxa-

tion from discipline is easier detected

and remedied." But the

removal or isolation of inept

sub-officers was only a negative

advantage. The true value of organizing

an institution around

small groups was that, through the use

of competitive devices,

groups could be made to control each

other as well as the behavior

of individual members. Reemelin

explained:

Each week the flag of honor waves over

that family which has had the

least amount of punishment-been the most

useful and orderly. The con-

tention for this mark of distinction

soon becomes so great, as often to

make it a matter of extreme difficulty

to decide to which the flag be-

longs; and who can doubt its most

beneficial effect upon officers and

inmates ?38

A tablet of honor recognizing

individual deportment supplemented

group competition and there was even a

Society of Honor, con-

sisting of exemplary former

"colons" who were to offer encourage-

ment to other released inmates. Upon

leaving Mettray, every boy,

whether or not he was returning to his

family, was assigned a

particular employment in a particular

place and also received a

patron, often a judge or local notable,

whose job it was to super-

vise the colon's behavior. Thus, the

institution's supervisory web

was extended into the child's later

years.

To Reemelin, the crowning virtue of

Mettray was that it

linked the cottage plan to agricultural

life and thus resembled

"life as it is, and not as

life should not be." The physical growth

36. "Intelligence: Colonie Agricole

de Mettray," Christian Teacher,

IV (N.S.) (1842), 208-19; "The

Child and the Criminal," Douglas Jerrold's

Shilling Magazine, II (1845-48), 228-39; Irish Quarterly, IV (September,

1854), 691-792; VI (1856), 785; Robert

Hall, Mettray, A Lecture Read

Before the Leeds Philosophical and

Literary Society (London, 1854). See

also Mary Carpenter, Reformatory Schools

(London, 1851) and Matthew

Davenport Hill, Suggestions for the

Repression of Crime (London, 1857).

37. Reemelin, Life, 137, 140.

38. Ohio. Docs., I (1856), 620.

Family System of Common Farmers 141

of the institution occurred

"gradually," in consonance with crop

development; in contrast, the house of

refuge ("the big house

cell system") was "generally

too large at the commencement, and

soon after too small for all coming

time." And, since "society in

general" lived life within a

"good farmer's family of easy, but not

rich circumstances," the

superiority of an institution similarly

organized became

"self-evident." "Habituate [the delinquent] to

the life and labor of a farm," said

Reemelin, "and he will, in

nearly every case, continue so to live

and labor when restored to

society." Once the public became

aware that the boys had been

taught "to live as industrious

people generally live, only with

greater regularity and under more steady

habits," families would

eagerly adopt them and the vexing

problem of placement would

be solved.39

Reemelin recognized that Mettray's

reputation rested not only

upon thorough supervision, but upon the

emotional aura of daily

life. The colony derived its style from

a combination of music,

physical activity, and military

exercises. In his report to the Ohio

legislature, Reemelin recommended,

"Instead of bells and gongs

use horns, with a few hearty blasts to

some simple piece of music,"

to regulate the day, and, "if

possible . . . bathing and swimming

... in open air, and in a running stream

should not be omitted."

Reemelin lauded DeMetz's employment of

subaltern army officers

as elder brothers because they produced

"a punctuality of conduct

that sets an excellent example." A

case in point, the famous

hammock drill, which Reemelin likely

observed, was described by

a British visitor:

When the little fellows marched

upstairs, they ranged themselves around

the room, keeping up the military tramp.

At the command, "a genoux,"

each was in one instant on his knees,

and from a corner of the room came

a weak, tiny voice beginning, Notre

Pere, que es aux cieux, the response

of the fifty was spoken as if one voice,

"ainsi." After prayer the order

was given to arrange hammocks, which was

done in three movements

each at the same second; they now put

off their clothes, as commanded,

and hung them on the hook beside their

hammock, and at the last order,

all were in bed.

Parades and public assemblies were held

often, giving individuals

and groups the opportunity to display

their badges and flags of

honor. Inmates were marched everywhere,

singing as they went.

This spirit, said DeMetz, "promotes good order,

prevents conver-

39. Ibid., 618-20.

142 OHIO HISTORY

sation ..., fixes good thoughts and

good words in their memory,

and attaches them to the institution

where they have first felt

these happy influences."40

The animating force of "these

happy influences" was the

superintendent and his staff. Reemelin wrote eloquently but

vaguely on this subject. The elder

brother "who will not... mingle

with the boys, eat, sleep, play and

work with them, should not be

employed," he said. With DeMetz in

mind, Reemelin wrote, "the

first officer . . . should not be a

hireling, but a man of sound

native sense, with a sound, practical

education, an honest, kind

and large heart, deeply religious and

strictly conscientious, but

not a bigot ... in short, a man who . .

. undertakes the position

from a deep conviction of duty, and not

for the mere pay, and the

great purpose of his life !"

Reemelin feared that he would not find

such a person in the United States; he

was especially impressed

by the remarks of a German Catholic

Bishop who accompanied him

to Mettray:

. . . you will not have the requisite

persons for the right economical ad-

ministration or the right religious

education.... Don't mistake me! I do

not say this as a Priest opposed to

Protestantism. I express it to you,

because I want to caution you against

the too high expectations, which I

see you have. In the U.S. they have not

yet learned the value of especially

capable public administration, by

servants in the best sense; to wit: that

of well disciplined persons, animated by

a stern public spirit, that has its

best reward in accomplishing high moral

good.41

But why was there no "stern public

spirit" in the United

States, or few officials acting

"from a deep conviction of duty?"

What did "sound native sense"

mean, besides skill in the techniques

of institution management? What set

Europe apart on these

questions? It must be emphasized that

DeMetz was a pioneer

penologist. At Mettray, he developed a

system of affective dis-

cipline substantially different from the

existing penal orthodoxy

which stressed rewards for industry and

silent obedience and

40. Ibid., 622; Reemelin, Life,

138; Irish Quarterly, Quarterly Record,

VIII (1858), vii-viii; Ibid, VI

(1856), 937-38, 975-77. Hammocks were neces-

sary because the space was needed as a

workshop during the day. They had

the added advantage of discouraging

homosexuality although an avid boy

of a later generation turned the barrier

to an advantage by draping

blankets over the side and congressing

on the floor. See Jean Genet, The

Flower and the Rose (Paris, 1951), 118-19.

41. Reemelin, Life, 140; Ohio. Docs.,

I (1856), 620-21.

|

Family System of Common Farmers 143 |

|

|

|

physical punishment for wrong doing. Employing a dynamic, personal style, he manipulated individual and group emotions to produce what he regarded as a more lasting reformation because the colon not only would obey the law but also would enthusiasti- cally share the values of his keepers. DeMetz epitomized his philosophy when, speaking of his inmates, he proclaimed that he would rather hold "the keys to their hearts than to their cells."42 Presumably then, Americans could merely copy the method. Or could they? Reemelin feared not, stressing the American passion for party politics which, he believed, filled the public institutions with corrupt, self-seeking officers. However, Reemelin's denunciations of American politics, coupled with his opaque rhetoric commending European philanthropists such as DeMetz, were really contradictory aspects of his larger faith in the metaphysical exist- ence of a strong state deriving its authority from the will of the people. As a German-American, Reemelin was caught half-way between the American belief, which coupled faith in the popular will with skepticism regarding the existence of a transcendent state, and the reality of mid-nineteenth century Europe, which

42. Ohio. Docs., I (1856), 621. |

144 OHIO HISTORY

was the exercise of state authority by

established classes who were

pleased to govern as representatives of

God or the metaphysical

state but who feared the will of the

people and rejected sovereignty

based upon it.

The connection between the philanthropy

of Mettray and

French privileged classes embarrassed

Reemelin to the point of

unaccustomed silence. DeMetz was a

member of the upper middle

class, but the institution owed its

existence to pious members of

the nobility who donated land and

endowed buildings. These men

were critical of both Louis Phillipe's

bourgeois monarchy and the

materialist philosophies of Comte and

St. Simon. They maintained

guarded ties to the regime through

educational reformers such as

Victor Cousin, but their real affinity

was for Catholic social action,

epitomized by the work of Frederic

Ozanam, founder of the St.

Vincent de Paul Society (1833). The

Revolution of 1848 posed a

dilema to this group, but not for long.

Ozanam welcomed the fall

of the monarchy, but when Republican

and radical workers in

Paris mounted the barricades he aided

Cavaignac and the National

Guards in brutally suppressing the

uprising. The colons joined

military units in large numbers; the

Eighth Regiment of Hussars

was called "Little Mettray."

The institution specially cited former

colons who participated in the Guards'

destruction of the barri-

cades on Faubourg St. Antoine, and a

picture depicting the death

of Monsignor Affre, Archbishop of

Paris, on the same battleground

was a prominent icon at Mettray.43

Reemelin ignored another connection

between Mettray and

French political conservatism by not

commenting upon the system

of Correction Paternelle which DeMetz

had inaugurated in 1854.

The term described two sections of the

French Civil Code allowing

parents to surrender unruly children to

the court for short periods

of imprisonment. Because of jail

conditions, parents, particularly

wealthy parents, seldom took this

action. Mettray itself, according

to DeMetz, was "unsuited" for

middle and upper class boys since

"they would . . . be liable to form

intimacies among their com-

panions which would be most injurious

in after life." At the

behest of affluent parents, DeMetz

established a building of separ-

ate and silent confinement modeled

after Pennsylvania's Eastern

43. Fondation d'une Colonie Agricole

pour Les Jeunes Detenus a

Mettray (Paris, 1839), 21-24; Thomas E. Auge, Frederic

Ozanam and His

World (Milwaukee, 1966), 20-55; 113-19; Irish Quarterly, VI

(1856), 954,

975-76. See also Jean Baptist Duroselle,

Les Debuts du Catholocisme Social

en France, 1822-70 (Paris, 1951), 154-98.

Family System of Common Farmers 145

State Penitentiary which he had studied

during his American visit

in 1837. Set apart from the main

institution, these youths sup-

posedly spent their incarceration

reflecting upon past misdeeds;

they saw only DeMetz and their private

teacher and confessor, who

was usually a seminary student. DeMetz

did not fully organize

La Maison Paternelle until 1858 but it

was functioning when

Reemelin visited.44

DeMetz vocally supported established

political and religious

authority because he believed in

class-based society and its central

tenet-the foreordination of a person's

life. By contrast, Reemelin,

who was not a reticent man, studiously

ignored plain evidences of

DeMetz's proudest beliefs. Indeed,

Reemelin encouraged quite

different goals for affective

discipline by insisting that the Ohio

Reform Farm would open the future for

its inmates. It would

provide "passports to the favors

of the world" by teaching them

"polite manners, clean habits, and

a capability to adapt them-

selves easily to each new family."

An elder brother at the Farm,

summarizing the philosophy of affective

discipline, commented on

its expected impact on individual

inmates:

I have no faith in negative goodness;

and, in my opinion, it is not enough

that a boy goes on from month to month

with a studied reticence and

persistent reserve, even though his

conduct be unexceptionable. Because

he does no evil, is not

sufficient reason that he is prepared to do any

good. [He may be perfect in the book of

Reports, without being well-

disposed in his heart.] ... Indeed, I

feel that in our zealous and unyield-

ing warfare against the evil in our

boys, we ought to bear in mind that

if a spirit of manly self-respect, a

love for good books, for study, and for

all things right and proper, can be excited in the

heart of the boy, it will

soon grow into a power that will do the weeding out for

us, even as the

weeds of the field are smothered by the shadow of the

vigorous, tower-

ing plant.45

For American reformers, knowledge of

common subjects, an

adaptable personality, "polite

manners", and "manly self-respect"

increasingly defined the meaning of

human character. These be-

came ends in themselves, more important

than individual or group

allegiance to established religious or

political authority. In his

44. Irish Quarterly, Quarterly

Record, VIII (1858), liv-lxx; Frederic

Auguste DeMetz and Abel Blouet, Rapports

a M. le Comte de Montalivit

. . . sur les Penitenciers des

Etats-Unis (Paris, 1837); Frederic

Auguste

DeMetz, Resume sur le Systeme

Penitentiare (Paris, 1847); Notice sur La

Maison Paternelle (Paris, 1860).

45. Ohio. Docs., I (1856), 621; Ibid.,

II (1867), 145.

146 OHIO HISTORY

report, Reemelin blurred the

distinction between religious and

moral instruction, emphasizing that

together these would form

the "citadel" of character

education at the Reform Farm. His

assurance, however, sounded less

convincing than his enthusiasm

for teaching "proper rules in

eating, drinking and sleeping." With-

out these "outposts", he

wrote, "human character, however deep

its religious foundations, cannot be

safely trusted to bear up

amidst the vicissitudes of life."

Religion could not be trusted to

control behavior, and politics existed

only to be scorned. "Is it not

enough," asked the Ohio

Commissioners, "that the greater part

of ... our ... governments, are tainted

by ... heated partizanship;

must the nurseries of youth be also

drawn into the vortex?46 Of

course, the Commissioners were

themselves "heated partizans."

But they had the good fortune to live

in a society where resources

were expanding and hierarchies were

fluid. Their luck permitted

them to believe that politics and

socialization were mutually exclu-

sive and that the American delinquent,

with his newly-formed

character, could be allowed to pursue

wealth and social standing.

After Reemelin left Mettray, he became

enmeshed in railroad

problems and spent little additional

time studying European reform

schools.47 He failed to

examine his own country's most famous

family reform school, Johann Hinrich

Wichern's Rauhe Haus in

Hamburg (Horn). He apparently knew

little about it, referring

in his Ohio report to the Rauhe Haus

located "at Wichern in

Germany." He did visit Gustav

Werner's schools for vagrant

children in Wurttemberg and some small

Swiss reform schools.

He admired Werner's self-denying zeal

and his ability to persuade

wealthy citizens to donate large sums.

Yet, Reemelin had to

intervene with these patrons in order

to relieve Werner of em-

barrassing debts and he knew from the

experience of the Cincinnati

Refuge that a reform school could never

be funded through volun-

tary contributions.48 Thus, as he returned to Ohio in

October,

46. Ibid., I (1856), 621, 623.

47. Reemelin knew little or nothing of

DeMetz's extensive penological

studies and their relationship to the

founding of Mettray. According to

DeMetz's own account, Mettray sought to

combine "l'ordre interieur et la

severite de la regle" of American

and English penitentiaries and "le

princepe du gouvernment paternel

l'organisation par families" of the Rauhe

Haus and, "enfin, a ces divers

etablissements, la nature des travaux et le

mode d'enseignement." See Fondation

d'un Colonie Agricole, 15.

48. Werner's schools continued to falter

because the apprenticed in-

mates "accustomed to punctuality,

to cleanliness, and to regularity in tak-

ing their simple meals, find it often

more difficult to get on well in less

regulated households." American

Journal of Education, XX (1870), 676.

Family System of Common Farmers 147

Mettray remained his primary

enthusiasm. It had given him a

technique.

Organizing the Farm

The Commissioners met several times in

late 1856 to face

the tasks of negotiating with the

Cincinnati House of Refuge and

of adapting Mettray to local

circumstances. They found Cincinnati

authorities open to discussion and

struck a quick bargain which,

though it ultimately fell through, had

the advantage of purchasing

the support of Hamilton County

politicians as the State Farm

was being funded and built. The

Commissioners exempted the

Refuge from legislation seeking to

encourage voluntarily supported

reform schools; to reciprocate, the

refuge agreed to allow the

Commissioners to visit and advise on a

regular basis. This conces-

sion cleared the path for the

Commissioners to recommend an

annual state subsidy of $10,000 in

return for which the Cincinnati

institution would accept up to 100 boys

"hereafter sent by the

courts in this state." Eighty

percent of these boys were to come

from outside Hamilton County; as a

group, they were characterized

as "of greater age and more

depraved, sent ... by judicial decision

only, and ... employed under rigid

restraint, chiefly in mechanical

and manufacturing labor."49

The Commissioners further enticed the

male managers of the

Cincinnati Refuge by proposing a plan

to rid the institution of

female delinquents. Since the girls'

conviction of morals offenses

had allegedly produced an

"unhealthy state of things," they were

to be separately confined in a

temporary institution. At the same

time, the state offered $5,000 to any

city or county establishing a

permanent institution. There were no

takers, even though the

subsidy was later increased. Eventually

(1870), the state built a

girls' reform school (the present

Scioto Village near Delaware).

In the interim, the alluring

possibility further stifled Cincinnati

opposition to a state reform school for

boys.50

The Commissioners' report of December,

1856 changed or

omitted several features of Mettray. In

deference to James Ladd's

Quaker pacifism, all mention of

military organization was deleted.

See also Johann H. Wichern, "The

German Reform School," American

Journal of Education, XXII (1871), 589-648.

49. Ohio. Does., I (1856),

617-18, 625; Ohio. Laws, LIV (1857), 171-77.

50. Ohio. Laws, LIV (1857),

171-77. See also Ohio. Laws, LV (1858),

33; Ebbert, Lancaster and Fairfield

County, 63-72.

148 OHIO HISTORY

The agricultural and horticultural

labor of the farm was to be

supervised by employees of the State

Board of Agriculture rather

than by elder brothers trained at the

institution. The Commis-

sioners believed that this practice

would not only provide expert

instruction but also eliminate

corruption in farm purchasing and

product sales. They hoped to induce the

Board to feed and clothe

the inmates in return for eight hours

of work, "because we think

Franklin was right in limiting labor to

that length of time."

Organized agriculture had another

role. County agricultural

societies were "to act as

auxiliaries in watching and guarding and

providing places for . . . dismissed

juveniles." Thus, state and

local agricultural organizations were

to be given greater super-

visory and parental powers than were

ever accorded to labor con-

tractors at prisons and refuges.51

The State Board of Agriculture rejected

this proposal almost

as soon as Reemelin made it at the

annual convention of county

agricultural societies. The Board cited

as reasons the novelty of

the institution and the prospect that

"the industrial direction of

the time of the inmates might seriously

interfere with the dis-

ciplinary government of the

institution." Beyond these, however,

was the desire to protect the status of

farming; the Board's princi-

pal enthusiasm, a land grant system to

support agricultural edu-

cation, was eventually realized with

the passage of the Morrill Act

(1862). Farm organizations wished to

portray their occupations

in the best light, and this desire

implied the exclusion of deviants.

In 1872, for example, the Ohio State

Grange had the following

creed: "To develop a better and

higher manhood and womanhood

among ourselves ... to maintain

inviolate our laws, and to emulate

each other in labor to hasten the good

time coming." Thus, it was

no wonder that the Reform School

Commissioners could get little

more than empty wishes of good will

from future meetings of the

State Board of Agriculture.52

Despite this early rebuff, the new

reform school bill (1857)

reflected the legislature's approval of

the Commissioners' year of

work. In addition to aiding the Cincinnati

Refuge, the law appropri-

51. Ohio. Does., I (1856),

623-24. There was an American precedent

for this plan. The farm labor at the

State Reform School, Westboro,

Massachusetts (1847) was supervised by

the Massachusetts State Board

of Agriculture. See Document C, attached

to above report.

52. Ohio State Board of Agriculture, AR

(1857), 84-86; Ibid., (1859),

122; Ibid. (1862), 3-4; Ibid. (1863),

16; The Farmer's Centennial History

of Ohio (Springfield, 1903).

Family System of Common Farmers 149

ated $15,000 to purchase one thousand

acres for a site and $10,000

for the first cottage, supplies and

salaries of all employees except

the "Acting Commissioner" or

superintendent whose annual salary

($1,500) was separately appropriated.

The dominant themes of

the institution were to be simplicity

and self-sufficiency. From

the beginning, the Commissioners had

contended that no architect

was needed to construct farmhouses and

buildings. The law re-

quired that all structures were to be

of "plain character" and that

no cottage cost more than $2,000.

Further, the Farm was to be

managed with the aim of making it a

"self-sustaining" institution.

The law proclaimed: "The state

shall incur only the expense of

the original purchase money, the

erection of permanent improve-

ments, and the outfit for the first

year."53

Following passage of the law, Chase

appointed Reemelin Act-

ing Commissioner with the understanding

that he was to devote

all of his time to the job. Foot and

Ladd were reappointed Ad-

visory Commissioners. As the author of

"the beautiful plan,"

Reemelin was the first among equals. In

the spring of 1857, he

began to search for land.54

There were good economic and

demographic reasons for

Reemelin to favor Fairfield County. It

was near the geographical

and population center of the state.

Lancaster, the county seat,

was connected by railroad and canal

with all parts of the Old

Northwest territory and the population

was overwhelmingly rural

and remained so throughout the

nineteenth century.55

Fairfield County was not devoid of

economic problems. Popula-

tion had declined by 1,000 during the

1840s and did not regain its

1840 level (31,858) until the late

1870s; six of the county's thirteen

townships had not reached their 1840

levels by the 1880 census.

The relatively poor fertility of much

of the land plus rapid defore-

station and careless farming largely

explains the outmigration.

Reemelin probably had Fairfield County

in mind when he lectured

the Ohio Board of Agriculture in 1862:

53. Ohio. Laws, LIV (1857),

171-77. See also, Ohio. Docs., I (1856),

619.

54. Chase to Reemelin, April 21, 1857,

Container 116, Chase MS, LC.

Reemelin, as usual, had a different

conception of the job; he never intended

to live on the farm. See Reemelin, Life,

142.

55. Even in 1970, after a century of

industrial growth and the spread

of metropolitan Columbus into the

county, Fairfield's population was

characterized as 44 percent urban while

the state level was 75 percent. See

U.S. Department of Commerce. Bureau

of the Census, Characteristics of

the Population; Ohio, Volume I, part 37, section 1 (Washington, D.C., 1973),

25.

150 OHIO HISTORY

Is Ohio, is our county, intrinsically

worth as much today as it was

seventy years ago? Is . . .

population-sustaining capacity as great?

Every year fewer phosphates, fewer

alkalies, fewer salts, fewer minerals

. . . we export life and import luxuries.56

Nevertheless, Reemelin selected as the

site for the Reform

School a 1,170 acre parcel located six

miles south of Lancaster in

the beautiful Hocking Hills. It was

offered to the Commissioners

by a syndicate headed by Henry Miers, a

local politician and land

speculator. Priced at $13.67/acre, it

was one of the highest of the

thirteen bids received both in per acre

and in total cost. Six of

the other parcels had lower per acre

costs and only one parcel had

a higher total cost. Also, as Reemelin

himself noted, the other

lands were more richly soiled and

Miers' parcel was unsuitable for

"corn raising and other heavy farming."

Tobacco and flax farming

had been unsuccessfully tried on a

portion of the land. What then

made the land attractive? Reemelin

emphasized the "unsurpassed

salubrity" of the climate and,

that unlike some of the other parcels,

the land was well-drained, non-malarial

and suitable "to the raising

of all kinds of fruit." Mettray's

horticulture plus Reemelin's own

farming experiences obviously

influenced his choice. Horticulture,

he believed, was not as demanding

physically as corn or wheat

farming and thus it was appropriate for

boys' labor. Further,

horticulture encouraged instruction in

conservation methods and

taught skills which Reemelin thought

were in short supply or soon

would be if Americans acquired a taste

for wine. The Miers land

would be an excellent laboratory and

gave at least the promise of

self-sufficiency. It had an adequate

supply of timber and was

proximate to the Hocking Valley coal

fields. Clear running water

crossed the property and two saw mills

were already in place.57

56. Henry Howe, Historical

Collections of Ohio, I (Columbus, 1889),

587; J. H. Klippart, "Condition of

Agricuture in Ohio in 1876" in Ohio

State Board of Agriculture, AR (1877),

535; Ibid. (1882), 347-54.

57. Ohio. Docs., I (1857),

606-07, 623-24; A. A. Graham, comp.,

History of Fairfield County (Chicago, 1883), 221. The average per acre

value of farm real estate in Fairfield

County was $22.00 in 1850 and

$36.00 in 1860. However, the figures for

Hocking County are more germane