Ohio History Journal

NANCY J. BRCAK

Country Carpenters, Federal

Buildings: An Early

Architectural Tradition

in Ohio's Western Reserve

The Western Reserve1 of Ohio was

settled, in large part, by New

England emigrants and, slightly later,

by upstate New Yorkers who

were themselves transplanted New

Englanders. These people, migrat-

ing west in the 1810s and 1820s,

brought with them a storehouse of

cultural tradition as well as dreams

for prosperity and success.

Both the architectural historian Talbot

Hamlin and the Ohio histori-

an I. T. Frary have recognized

connections between Ohio and New

England architecture during the early

nineteenth century, with Frary in

particular emphasizing the close ties

between the Reserve and New

England.2 While one might

not wish to go so far as one cultural

historian who said, "On the

Reserve a 'way of life' was lifted from its

Atlantic mooring and deposited in a new

setting,"3 still it is important

to realize that the cultural heritage

of this area is deeply rooted in New

England. The Western Reserve,

originally known as the Connecticut

Reserve, was a large parcel of land

claimed by the colony of Connecticut

Nancy J. Break is Assistant Professor

and Chair of Art History at Ithaca College.

1. The Western Reserve is that portion

of Ohio extending south from Lake Erie to

the forty-first parallel, that is, a

line slightly south of present-day Ohio Route 224, and

west from the Pennsylvania border

approximately 120 miles to the western edge of Erie

and Huron counties. Completely within

the boundaries of the Reserve are the modern

counties of Ashtabula, Cuyahoga, Erie,

Geauga, Huron, Lake, Lorain, Medina, Portage,

and Trumbull. Straddling the southern

border but located largely within the Reserve are

Mahoning and Summit counties.

Additionally, a small section of land, originally part of

Huron county but today comprising the

northern tip of Ashland county, completes the

land package known as the Western Reserve.

2. Talbot Hamlin, Greek Revival

Architecture in America (New York, 1944), 280,

and I. T. Frary, Early Homes of Ohio (reprint

ed., New York, Dover, 1970), 3.

3. Kenneth Lottick, "Culture

Transplantation in the Connecticut Reserve," Bulletin

of the Historical and Philosophical

Society of Ohio, 17 (1959), 155.

132 OHIO HISTORY

in the seventeenth century and, after

the Revolution, sold primarily to

the citizens of Connecticut and other

New England states.4

Many New Englanders coming to the

Reserve brought with them a

penchant for the Federal style in

architecture. An early manifestation

in America of the international movement

of Neoclassicism, Federal

architecture was extremely popular in

America's Northeast. The style

featured block-like forms decorated with

the slim, classical detailing

made popular by the contemporary English

architect, Robert Adam.

Most Ohio carpenters of the late 1810s

and 1820s did not know Adam,

but they were aware of the work of his

most accomplished American

followers, principally the Massachusetts

architect, Charles Bulfinch

(1763-1844) and his protege, the

carpenter and author, Asher Benjamin

(1773-1845).

If Reserve builders favored the

neoclassical forms that had been

popular in Federal New England from the

late-eighteenth century

onward, they learned to create

Federal-style buildings by observing

existing structures and participating in

the construction of new build-

ings under the supervision of

experienced craftsmen. Additionally,

Western Reserve builders, again

following the tradition of New England

craftsmen, would often rely upon

contemporary carpenter's manuals,

also called handbooks or pattern books,

to aid them in their projects.

Among pattern book authors, the most

important transmitter of the

Federal style was Asher Benjamin, the

Greenfield, Massachusetts,

carpenter who had worked for Bulfinch.

Benjamin's pattern books also

proved invaluable to the country builder

as guides for solving problems

of construction, to such an extent that

Hamlin, in his exhaustive study

of early nineteenth century building,

concluded, "From 1800 on, the

country work obviously is deeply

indebted to the books of Asher

Benjamin."5

Prior to the popularity of the Federal

style, the Reserve's initial

frontier period of 1800-1815 saw the

construction of rudimentary

dwellings-usually log cabins-to serve

strictly functional purposes.

These structures often stood at the

center of a plot freshly cleared of

trees but surrounded by stumps. Early

arriving immigrants did all the

4. Also among the initial group of

buyers were residents of upper New York State,

many of whom, not long before, had

migrated from New England. The complicated yet

fascinating story of Connecticut's claim

to northeastern Ohio cannot be told in full here.

See Harlan Hatcher, The Western

Reserve: The Story of New Connecticut in Ohio

(Indianapolis, 1949).

5. Hamlin, 165. For more information on

Benjamin, see also John Quinan, "Asher

Benjamin and American

Architecture," Journal of the Society of Architectural Histori-

ans, 38 (1979), 247-48.

Country Carpenters, Federal

Buildings

133

work themselves, but later settlers were

welcomed by their neighbors

with house or barn raisings. Cabins,

plain and rough, were built of logs

and chinked with mud and lime. They had

earthen floors, a single door,

and were often windowless. More

sophisticated examples had fireplac-

es and chimneys; however, some settlers

skipped such fine points and

simply laid fires on the floor of the

dwelling.6

Architect-builders who arrived early in

this area, such as Jonathan

Goldsmith who migrated to Ohio in 1811,

at first found no demand for

their expertise. Elizabeth Hitchcock, a

biographer of Goldsmith,

reports that the New Haven-trained

builder was forced to work as a

cobbler to support his family until the

post-war boom provided a

market for his services.7 However,

about 1818, Jonathan Goldsmith

was joined in the Western Reserve by a

number of other New

England-born builders who favored the

Federal mode. These men

included another native of Connecticut,

Willie Smith, who in Ohio

created structures in and around the

Trumbull County town of Kins-

man; and Lemuel Porter, formerly of

Waterbury, Connecticut, who

worked in Hudson, Tallmadge, and

Atwater, in present-day Summit

and Portage counties.

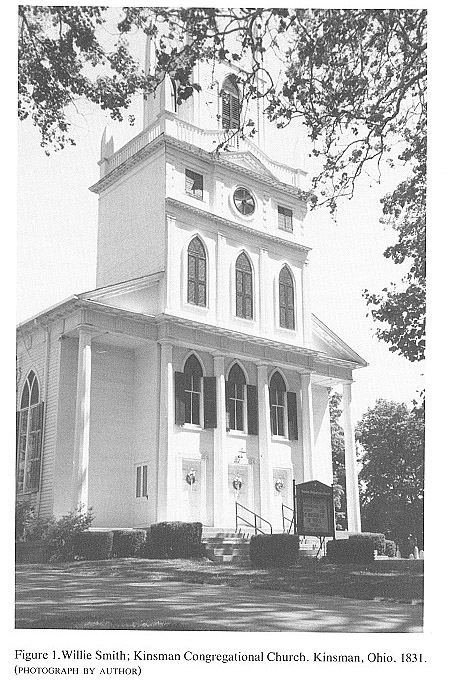

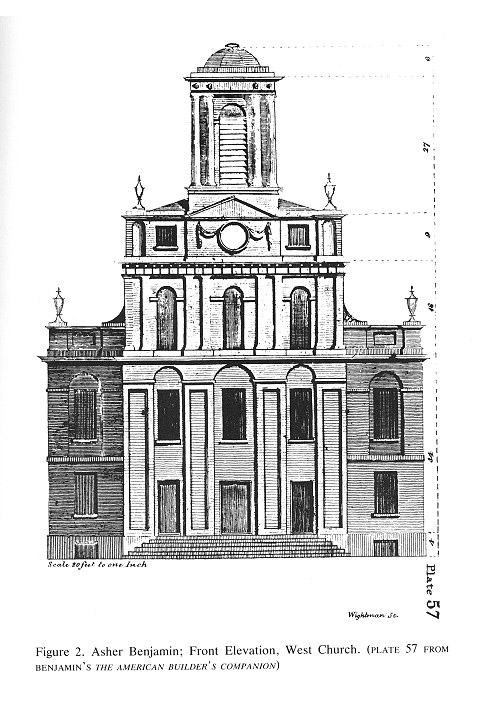

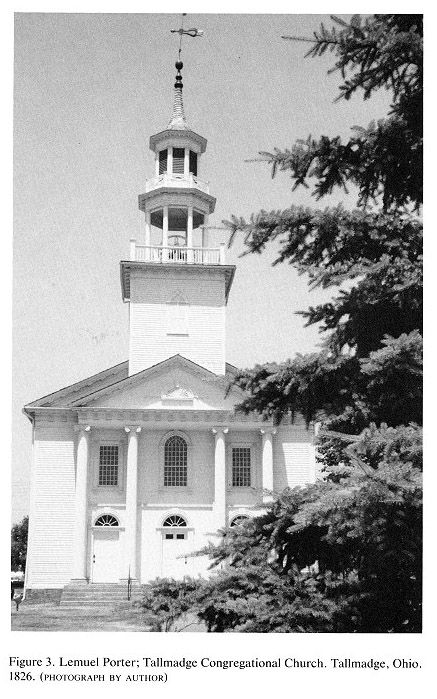

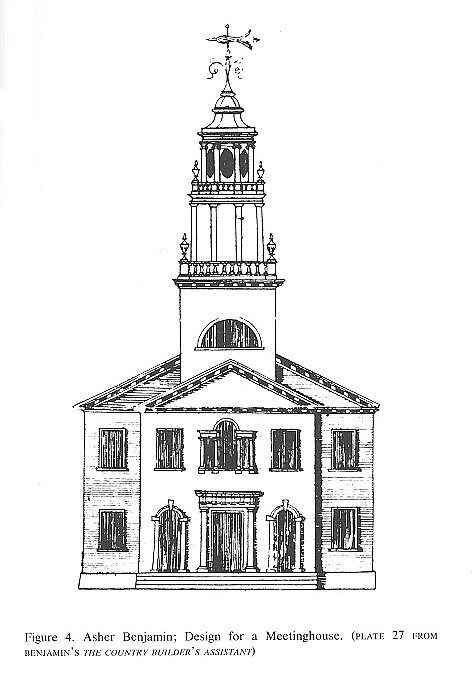

It is interesting to note that both

Smith and Porter created churches

based on Federal-style designs found in

Asher Benjamin's pattern

books. Smith's masterpiece, the Kinsman

Congregational Church of

1831 (Fig. 1), is based on Benjamin's

"Design for a Church" in The

American Builder's Companion of 1806 (Fig 2).8 Lemuel Porter's

Tallmadge Congregational Church, 1826

(Fig. 3), is one of the finest

interpretations of Plate 27 of

Benjamin's The Country Builder's Assis-

tant (1797; Fig. 4) created during this period.9 Thus,

when taking on

6. Hatcher, 84.

7. Elizabeth Hitchcock, Jonathan

Goldsmith (Cleveland, 1980), 5-7.

8. The front elevation of each design

features a projecting center section divided

horizontally and vertically by various

architectural members. Resemblance to Benjamin's

Plate 57 is strongest in the upper

portion of the Kinsman facade where the pattern of

fenestration is nearly identical with

that of the pattern book design. Both the Benjamin

and the Smith plans feature a

rectangular vestibule with staircases placed along the short

walls; each anteroom opens into an

ample, rectangular auditorium containing an elevated

pulpit. Positioned on the wall opposite

the entrance, and flanked by pews that face

inward toward it, the elaborate pulpit

is the visual focus of the room. Benjamin's design,

large in scale and complex in detail,

was an appropriate choice for a church project in the

thriving town of Kinsman.

9. Porter's Tallmadge church has

elsewhere been likened to the Congregational

Church at Old Lyme, Connecticut

(1816-1817), designed by Samuel Belcher. See

William H. Pierson, Jr., American

Buildings and their Architects: The Colonial and

Neo-Classical Styles (Garden City, New York, 1976), 239, for comments and an

illustration. However, it should be

understood that these two architects shared a

common source, Plate 27 in the first edition

of Benjamin's Country Builder's Assistant

(Fig. 4).

134 OHIO HISTORY

large and complicated projects, even

experienced carpenter-builders

felt more comfortable when proceeding

with a trusted pattern book in

hand. With this link to Benjamin,

architecture in the Reserve parallels

developments elsewhere in America.

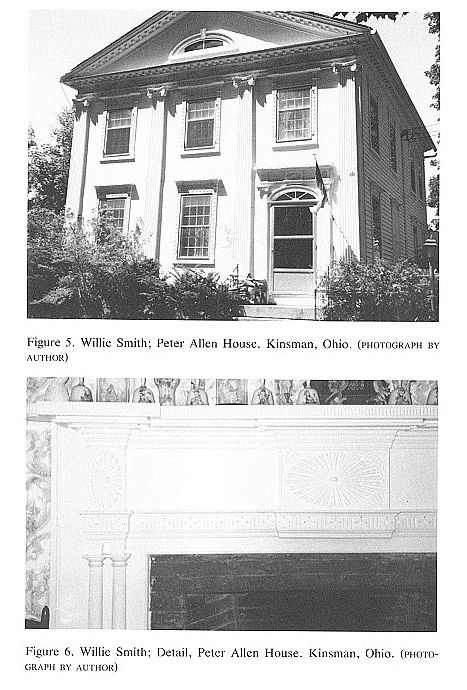

Willie (or Willis or William) Smith is

believed to have migrated to

Kinsman, Ohio, about 1818.10 Ten years

before undertaking the large

Congregational Church project, he

designed the breathtaking Peter

Allen House (1821; Figs. 5 and 6). While

several details of this building

can be traced to plates in Benjamin

handbooks, the Allen house should

also be considered in the context of the

much admired work of the

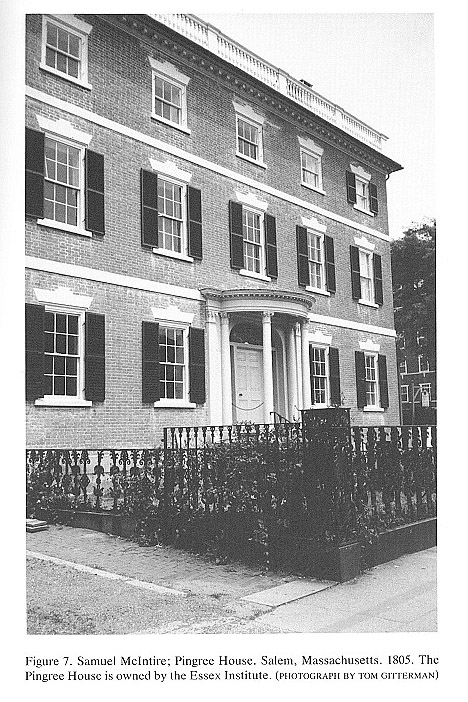

woodcarver, Samuel Mclntire (1757-1811)

of Salem, Massachusetts

(Figs. 7 and 8). McIntire's designs were

widely admired by his peers

and are still recognized as

exceptionally well conceived and well

executed; and while he did not invent

the character of Federal

ornament, he did perfect certain motifs

that came to be used by country

builders throughout Federal America.

Like McIntire, Willie Smith concentrated

his delicately carved

detailing at certain focal points, such

as mantelpieces and door and

window surrounds. Smith's detailing has

a decidedly linear quality

which brings to mind the interior decoration

of Mclntire's Pingree

House (Fig. 8). (By contrast, Mclntire's

exterior detail is restrained

and sparse.) And Smith's motifs,

including the swag (Fig. 5) and the

sunburst and ellipse (Figs. 5 and 6),

also recall the Salem craftsman's

work. Yet Smith broke with the Mclntire

formula by placing on the

exterior of the Allen House a profusion of neoclassical

detailing

(Fig. 5). His use of classically correct

Ionic pilasters and entablature is

also evidence of the presence of a newer

style, the Greek Revival, on

the Ohio landscape. Thus the Western

Reserve carpenter, aware of

architectural developments taking place

in the East, showed the

confidence and exuberance of the

frontiersman by borrowing freely

from a variety of artistic sources.

Although information on Willie Smith's

background and training is

sketchy, a bit more is known about the

life and work of Lemuel Porter

(1775-1829). An established builder

trained by Lemuel and James

Harrision of Waterbury, Connecticut,

Porter probably came to the

Reserve at the urging of another son of

Connecticut, David Hudson,

founder of the town of Hudson, Ohio.11 Lemuel

Porter created

buildings for Hudson's newly established

Western Reserve College.

10. Florence McLean Davis, Kinsman

Memories (Warren, Ohio, 1970), 10.

11. Grace Goulder Izant, Hudson's

Heritage (Kent, Ohio, 1985, 86), 153-55, and

Frary, 93.

Country Carpenters, Federal

Buildings 135

(David Hudson, a Yale graduate, saw to

it that the area's first college

was located in his "back yard"

by providing much of the land on which

the campus was built. He could not

foresee that his beloved institution

would later be moved to Cleveland and

transformed into a larger

university, Case Western Reserve.)

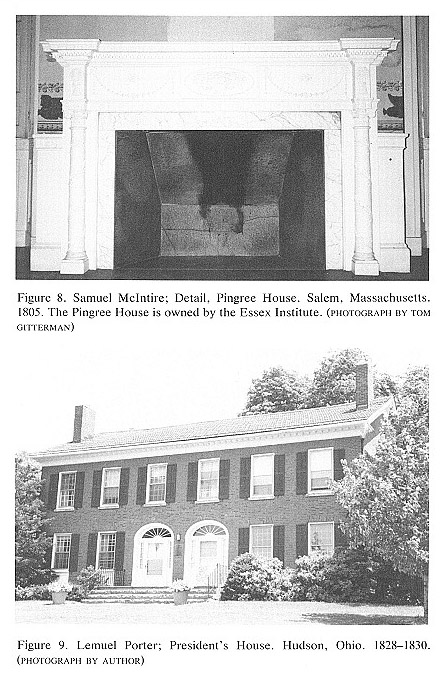

Lemuel Porter's last completed structure

for the Western Reserve

campus was the President's House

(1828-1830; Fig. 9). Once again the

decorative vocabulary is taken from the

pages of Asher Benjamin,

although the form of the structure-a

six-bay double house-does not

resemble any found in Federal pattern

books. Unfortunately, the

promising career of Lemuel Porter was

cut short by his early death,

and the commissions awarded by David

Hudson to Porter were turned

over the the architect-builder's son and

assistant, Simeon. The younger

man chose to design in the more

progressive Greek Revival style and

to abandon almost completely the Federal

mode his father had

mastered so thoroughly.

Penetrating further into the fabric of

Federal architecture in the

Western Reserve, one finds a host of

builders more obscure than

Jonathan Goldsmith, Willie Smith, and

Lemuel Porter. In many cases

these individuals built only their own

homes. The work of these

minimally trained, part-time craftsmen

is essentially vernacular in

character, meaning that it employs the

ordinary, everyday language of

building and only to a limited degree

the language of "high style"

architecture.

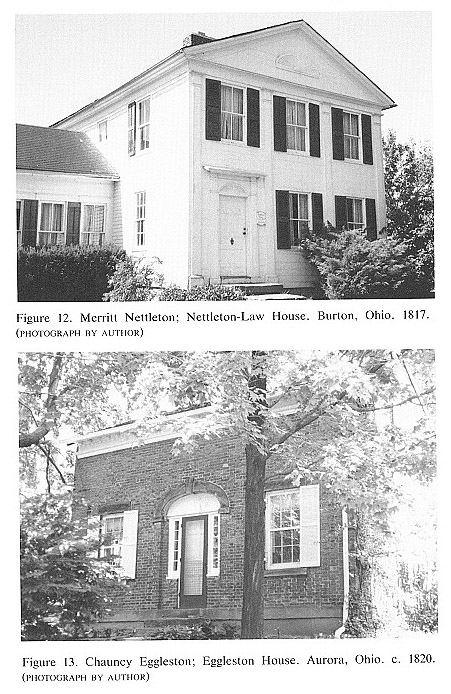

Taken as a whole, the Federal vernacular

work that survives by

these little-known builders can be

characterized as simple in form and

restrained in decoration. Yet, within

such limits these structures

display a diversity that testifies to

their authors' imaginations. Build-

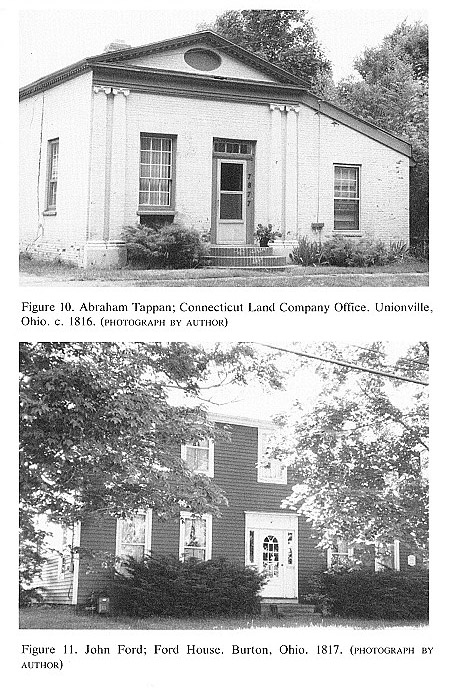

ings such as Abraham Tappan's

Connecticut Land Company Office,

Unionville (c. 1816, Fig. 10); the Ford

Homestead, built in Burton by

John Ford in 1817 (Fig. 11); the

Nettleton-Law Residence, also in

Burton, built by the original owner,

Merritt Nettleton, in 1817 (Fig. 12);

and the Chauncey Eggleston House (Fig.

13) in Aurora, fashioned by

Eggleston about 1820, attest to this

diversity. No particular orientation

or size prevailed. The Tappan and

Nettleton buildings are deeper than

they are wide, with ridge poles placed

perpendicular to the street, while

the Ford and Eggleston houses are wider

than they are long, conceived

in the tradition of the detached houses

of colonial and post-colonial

New England. The Nettleton and Ford

homes are fully two stories in

height, while the Eggleston house is a

story-and-a-half and the Tappan

structure, a single story.

Western Reserve carpenters utilized the

limited variety of materials

available to them. The building resource

most plentiful in early-

|

136 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Country Carpenters, Federal Buildings 137 |

|

138 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Country Carpenters, Federal Buildings 139 |

|

140 OHIO HISTORY |

|

Country Carpenters, Federal Buildings 141 |

|

142 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Country Carpenters, Federal Buildings 143 |

|

|

|

144 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

Country Carpenters, Federal

Buildings 145

nineteenth-century Ohio (as in New

England) was wood, and two of

these four buildings are frame. However,

both the Eggleston home and

the Land Office building are made of

brick, the material favored by the

more sophisticated Federal designers of

New England. In fact, "Gen-

eral" Eggleston made brick for his

house from clay dug on the

property, and the limestone for the

detailing and mortar was quarried

on the neighboring Sheldon farm.12

Clearly, even in these early works the

owner-builders were interest-

ed in more than shelter. A sense of

pride in the form and appearance of

the building-perhaps even a slight

tendency toward "grandeur"-was

part of the Western Reserve carpenters'

thinking.

The amount, placement, and nature of

detailing on these structures

further testify to the diversity of

Federal architecture in the Reserve as

well as to the ambition of the country

builders.13 On the Nettleton

House, the motif of cornice and frieze

with supporting pilasters which

graces the facade is echoed in a similar

treatment of the doorway. By

contrast, detailing on the Ford building

is concentrated solely in the

area of the entranceway, where

delicately mullioned sidelights and a

carved lintel are the principal

adornments. The doorway is the focus of

the Eggleston House, too, but here the

massive, elliptical limestone

arch sets a tone decidedly more bold

than the fragile linearity of the

Ford decoration. In yet another

approach, Tappan created his detailing

in both brick and wood. Brick pilasters,

capped with carved Ionic

capitals, support a full, wooden

entablature; above, the raking,

modillioned cornice of the pedimented

end gable originally framed an

elliptical wooden ornament.

Depending upon the country designer's

level of skill, the Federal

mode could give rise to simple sturdy

buildings or more elaborately

decorated ones. In this context it is

useful to compare similar houses,

one designed by an informally schooled

builder and one by a profes-

sional craftsman. Merritt Nettleton's

house for himself (Fig. 12) and

Willie Smith's Allen House (Fig. 5) are

both two-story, rectangular

structures with gabled roofs,

clapboarding, and flush siding applied to

their front walls; each facade features

four two-story pilasters support-

ing a horizontal member, a

semi-elliptical decoration in the pediment,

and an off-center doorway. Yet, the

Tuscan pilasters and partial

entablature of Nettleton's house cannot

match the richness of detail

and sophisticated carving displayed on

the Allen facade: the frieze of

12. Richard N. Campen, Architecture

of the Western Reserve, 1800-1900 (Cleveland,

1971), 129.

13. Similarities should also be noted,

among them the inclusion of an ornament in the

pediments of the Tappan and Nettleton

buildings, the use of pilasters on these two

146 OHIO HISTORY

Smith's full entablature is decorated

with a swag motif, his finely

crafted Ionic pilasters are fluted, and

the cornices are decorated with

dentils. Nettleton's naivete is

especially evident in the area of the front

doorway where his fan decoration

intrudes upon the frieze in a

decidedly unclassical way. Additionally,

the proportions of the detail-

ing on the Nettleton home are awkward

and unclassical in comparison

to those of Smith's work. It is tempting

to say that Nettleton employed

the vocabulary of Federal architecture

to write prose, while Smith used

it to create poetry.

Federal architecture in the Western

Reserve, distant from "high

style" centers of culture, was both

inhibited and enhanced by the skills

and sensibilities of its builders. In

some cases, as in the Nettleton

House, the carpenter was unhampered by

the restrictions of neoclas-

sical "correctness"; in other

instances, including Smith's Allen House,

greater knowledge of classical

vocabulary is expressed vividly through

the craftsman's skill.

The creative achievements of these

country carpenters serve to

represent the overall output of the

early Reserve builders working in

the Federal idiom. After choosing from a

variety of established,

familiar building types, each designer

added decoration taken from the

general vocabulary of Federal

architecture (culled from memories of

existing structures and/or derived from

carpenter's handbooks) but

suited to his own taste and skills.

These buildings represent the

"countrified" version of the

New England Federal style of Bulfinch,

Benjamin, and McIntire that was so

characteristic of Reserve archi-

tecture around the year 1820.

In the Western Reserve, the Federal

style was of primary importance

in those areas which were settled early.14

Thus, this mode was

prominent in the northeastern and

southeastern counties but much less

significant in the Reserve's

southwestern counties, which were settled

primarily in the 1830s and 1840s, and

where only an occasional New

England immigrant or two stubbornly

refused to abandon the style of

his father.15

structures, and the articulation of

window and door surrounds on the Nettleton and

Eggleston houses.

14. The Federal style was also popular

elsewhere in Ohio during the first quarter of

the nineteenth century. For example, in

the southeastern portion of the state the Ohio

Land Company of New England settled what

is now Washington County and filled its

principal settlement, Marietta, with

handsome Federal buildings in the Benjamin-

Bulfinch tradition. Chillicothe and

Cincinnati, further to the west, are also rich in Federal

structures; in the 1810s and 1820s these

areas were populated by a mix of emigrants from

Kentucky, Virginia, and New England.

15. For example, in the southwestern

county of Medina, Connecticut natives Ed and

Matthew Chandler built Federal style

houses during the 1840s.