Ohio History Journal

|

AN ACT For the relief of the families of volunteers

in the State or United States service. SECTION 1. Be it enacted by the

General Assembly of the State of

Tax levied, Ohio, That for the relief of the necessities of the families of volun- three-fifths of a teers who now are, or hereafter may be, in the service of this state mill

on the or the United States, there be and hereby is levied and assessed, for dollar

valua- the year 1862, three-fifths

of one mill on the dollar valuation on the tion. grand list of the taxable property of the State; and the amount so Collected

as levied land assessed shall be collected in the same manner as other taxes. state taxes are collected. LAWS OF OHIO,

1862 Title and first section of an act passed by the Ohio General Assembly, February 13, 1862 |

|

RELIEF FOR SOLDIERS' FAMILIES IN OHIO DURING THE CIVIL WAR by JOSEPH E.

HOLLIDAY One of the aspects of the Civil War on the home front

which has received scant attention by historians is that of aid for the

families of men in the armed services. The work of the United States

Sanitary Commission and the United States Christian Commission has been

recognized, but the ex- tensive work of these commissions was chiefly for

the welfare of the soldiers themselves. The impact of the war on those who were

left behind when the breadwinner was called to serve at the front has

received little attention. Yet to the communities both North and South in which

these families lived, common justice, humanity, and the level of morale

demanded that the soldiers' dependents be reasonably secured against

real privation. A number of methods for the relief of soldiers'

families were used in the state of Ohio. During the Civil War it was the

third most populous state in the Union, with a population in 1860 of

2,339,511. The complete story of this relief can never be told, inasmuch as a great

deal of it was given through local and private sources and data are

either lacking or are too difficult to trace. However, some information

regarding this phase of it is available for the city of Cincinnati and Hamilton

County. At that time Cincinnati was the largest city in the

state--indeed, it was the largest city west of the Alleghenies, with a population in 1860

of 161,044. The various methods of aiding the families of soldiers in that

city can serve as some indication of those used in other cities in the

state and in the West. Communities in Ohio were little prepared in 1861 to

take care of the unforeseen needs of soldiers' families, except by

the existing system of NOTES ARE ON PAGES 194-196 |

98 OHIO HISTORY

outdoor relief (that is, of needy

persons living in their own homes). It was

at first expected that bounty money and

part of the soldiers' pay would

supply most of their needs. But this did

not prove to be true even during

the first year of the war, and local

governmental units and private charity

supplemented the private resources of

many of these families. Few could

foresee the magnitude of the problem and

the continuation of the war for

four long years.

By the end of 1861 it became apparent

that the local governmental units

and private benevolence could not

sufficiently provide for them. State taxa-

tion for this purpose was first used in

Ohio in 1862, and the pressure for

voluntary gifts was accelerated. The

condition became especially serious

during the winter of 1864-65. By the end

of the war considerable sums

from a variety of sources were being

expended for the relief of the families

of the men fighting to preserve the

Union. By that time additional depend-

ents had made their appearance--war

widows, orphans, and disabled

veterans--for whom somewhat different

methods of relief came to be devised.

Among the first actions of the Ohio General

Assembly after the outbreak

of hostilities in April 1861 was the

protection of the property of citizen-

soldiers while they were away from home.

An act of May 1, 1861, ex-

empted from execution the property of

any soldier in the militia of Ohio

mustered into the service of the United

States during the time he was in

that service and for two months

thereafter.1 It was later (March 10, 1862)

extended to all volunteers from the

state in the service of the United States.2

In February 1862 the general assembly

sought to protect citizen-soldiers

charged with criminal offenses by

providing that judges should postpone

their trials until they were discharged.3

Still later, in March 1864, certain

relief was given to debtors in the armed

services who might have judgment

rendered against them without defense;

they were given the right to reopen

the case within one year after their

discharge from the army.4 By such

legislation the property of the citizen-soldier

and his family was given a

measure of protection while he was

serving his country.

After the first flush of patriotic

enthusiasm had passed, one of the strong

inducements to enlistment was a

financial one--a bounty, and, at a later

date, the advance of the first month's

pay. A complete discussion of the

complicated bounty system is beyond the

scope of this article, but some

consideration of it is necessary, since

bounty money was generally used for

family aid. The system was, of course,

not new at the time of the Civil

War; its origins go back to the colonial

wars. In his first address to the

soldiers of Ohio on May 17, 1861,

Governor William Dennison reminded

them that

RELIEF FOR SOLDIERS' FAMILIES 99

the [federal] government, with

solicitous care, makes provision for the families

of those who may fall or be disabled in

the National cause.

It offers a bounty of one hundred

dollars to all who may enlist, payable at

the close of the service, or to the

soldier's family, if he should not survive.

The system of bounty lands is also a

permanent one.5

Provost Marshal General James B. Fry

stated after the war that to stimulate

recruiting it had been necessary to

offer "inducements intended to compare

favorably with the price of ordinary

labor and at the same time provide

means for the support of the family or

others dependent on the labor of

the recruit."6 Thus it

was generally assumed that all or part of the bounty

money would be given to his family by

the volunteer. After a study of the

subject many years ago Professor Emerson

D. Fite wrote that "undoubtedly

one-half" of the bounty "was

turned over by soldiers to their needy relatives

and may be looked upon as a form of

relief."7

During the Civil War, bounties came from

three sources--the federal

government, local governmental units,

and private subscription. (In Ohio

there was no bounty offered directly

from state funds.) The federal govern-

ment, at the beginning of hostilities,

offered a bounty of $100, payable upon

honorable discharge. Its post-service

payment, however, was of little help

in the family emergency immediately

following the enlistment of the bread-

winner. Consequently, by action of

congress in July 1862, one-fourth of

this sum was to be paid upon muster and

the balance at the expiration of

the term of service. By later acts of

congress the bounty was increased to as

much as $400 in some cases, payable in

installments at certain periods during

the soldier's service as well as upon

his being mustered in and mustered out.

By 1863 the volunteer could expect $75

from the federal government at

the time he was mustered in, $13 of the

amount being his first month's pay.8

To the federal bounty there came to be

added bounties provided by local

governmental units and private

subscription. Indeed, as the provost marshal

general wrote, the federal bounty paled

into "comparative insignificance"

when compared with "the exorbitant

bounties paid in advance by local au-

thorities." These, he believed,

were the most mischievous in encouraging

desertion, bounty-jumping, and other

evils connected with the system. So

great was the stigma of the draft that

local authorities were highly competi-

tive in the amounts offered to

volunteers. Furthermore, they paid all the

sum in advance. The primary objective of

these payments, as General Fry

put it, came to be "to obtain men

to fill quotas."9

Localities began by offering moderate

bounties. In 1862 the average

local bounty in Ohio was estimated at

$25; in 1863 it advanced to $100;

in 1864 it bounded to $400; and in 1865

the average bounty was $500,

100 OHIO HISTORY

although in some localities it was as

high as $800.10 The Hamilton County

Board of Commissioners levied a tax of

two mills in 1863 to take care of

local bounty payments. On a tax

duplicate of $128,432,065 this levy

yielded about $256,864.11 This appears

to be the only year of the war in

which a county levy for bounties was

made in Hamilton County. The next

year (1864), however, the city of

Cincinnati began to borrow in order to

offer city bounty payments, and during

that year 1,811 volunteers were

paid bounties of $100 each.12

After the war the adjutant general of

Ohio estimated that $54,457,575

had been paid in local bounties

throughout the state, of which amount cities

and counties had paid about $14,000,000

and private subscribers, $40,-

457,575.13 The private subscriptions

usually represented ward or township

bounties, offered to encourage

volunteering to avoid the draft in a city ward

or township. Ward military committees

were very active in securing private

contributions for this purpose, as well

as in securing volunteers. Bounties,

then, must be considered an important

source of income for the soldiers

and their families throughout the war.

Another way in which the individual

soldier was able to help his family

while in the armed services was to

assign all or part of his pay to his

relatives back home. This method was

known as the "allotment system."

Although the navy had developed an

allotment system before the war, the

army had not done so. At the beginning

of the war the soldiers used a

number of informal methods to send money

home. Congress then made it

possible for the states to establish

systems of collection for this purpose.

Early in the war great expectation was

placed in this source to provide an

income for soldiers' families. The pay

of a private soldier was fixed at $13

per month soon after the beginning of

the war; in May 1864 it was raised to

$16 per month. As Bell I. Wiley has

pointed out, "in comparison with that

[the pay] of World War II it was

lamentably low."14 But in addition to

their pay, most of the volunteers received

installments of their federal

bounties at stated intervals while they

were in the field, and the amounts

they often received there were larger

than might be inferred. Allotments

were arranged directly by the men in the

field; they were not automatically

deducted from their pay in a central

office far behind the lines. When General

William T. Sherman's army arrived in

Atlanta in September 1864, the men

had not been paid for a number of weeks.

In writing to the secretary of

war, Sherman said he believed that only

one-tenth or one-eighth of their

pay would be necessary in cash--the

balance would be returned North to

their families.15 This

indicates a rather large allotment by the average

soldier to his family back home.

|

RELIEF FOR SOLDIERS' FAMILIES 101 |

|

|

|

In the absence of an official method at the beginning of the war of re- turning their pay home, the soldiers resorted to various schemes. In some cases they sent it by express or through the mail and there was considerable loss by these means.16 At one time the Tenth Ohio Volunteer Infantry, com- manded by Brigadier General William H. Lytle, sent to Cincinnati by one of its sutlers, John Ferguson, about $13,000 to be distributed by him to relatives.17 On several occasions German soldiers sent sums to Benno Speyer, a highly trusted and prominent leader of the German element in Cincinnati. In April 1862 he received $14,000 from the Twenty-Eighth Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Second Regiment; two months later he received $25,000 from the same regiment. Notice was placed in the newspapers, and relatives were asked to call at his office to collect.18 In the autumn of 1861 the Hamil- ton County Board of Commissioners, besieged with requests for relief from the families of soldiers, sent Leonard Swartz to western Virginia, where several companies of Hamilton County volunteers were stationed, to per- suade them to send part of their pay home with him.19 A few days later the Cincinnati City Council authorized its representative, Theodore Marsh, to go to the same area for the same purpose. He returned with $13,250 from the Fifth Ohio Volunteer Infantry.20 Such methods were the only ones available to the soldiers during the early |

102 OHIO HISTORY

months of the war, and they were

unsystematic and irregular. Clearly a

more satisfactory means was needed. In

July 1861 congress hastily author-

ized the secretary of war to introduce

among the volunteers "the system of

allotment tickets now used in the navy,

or some equivalent system," but the

secretary failed to act.21 In December

1861 Congress passed the basic

allotment act for army volunteers. Upon

nomination by state governors, the

president could appoint not more than

three commissioners from each state

to visit the several army departments to

procure allotments. Such commis-

sioners were expressly denied any

"pay or emolument" from the federal

treasury. It was clear that congress

expected that the states would take the

initiative and the responsibility for

allotments. This law also repealed an

act of 1858 which gave to sutlers a lien

on the pay of soldiers.22

In February 1862 the general assembly of

Ohio passed a law enabling

soldiers "to transmit their pay to

their families or friends." Allotments

were to be paid into the state treasury;

the state auditor would then notify

the various county auditors of the sums

and to whom payments were to be

made; and the county officials would

then disburse such money. These sums

were expressly exempt from any

attachment or other legal process for the

satisfaction of any debt or liability.23

Two months later (April 14, 1862)

this basic law was implemented when

state pay agents were authorized who

would visit the various army departments

to procure allotments.24 By

channeling this money through the state

treasury, its safety was assured.

The state auditor believed the method to

be "simple, direct and certain,"

but the first use of pay agents was only

partly successful, and by the end of

1862 there was only one pay agent in the

state's service.25 A supplementary

law was enacted in April 1863 under

which three state officials, known

as allotment commissioners, were to be

recommended to the president and

appointed by him. They supervised the

collection of allotments.26 Gover-

nor Tod recommended Ridgley J. Powers of

Youngstown, Henry N. Johnson

of Cleveland, and Loren R. Brownell of

Piqua. By the end of the war Ohio

had sixteen pay agents at various

points.27

The treasurer of state reported at the

end of the war that $8,470,494.76

had been received in the allotment fund

of the state treasury since it was

established in February 1862, "without

cost to the soldier, and without fee

or charge by the officers of the State

or county treasuries."28 But nearly half

of that amount was collected during

1865. There is no doubt that the Ohio

system protected the payments from any

embezzlement or dishonesty. The

chief criticisms were based on the

irregularity of payments and the delays

involved. For example, during the year

1863 the monthly receipts paid into

the Ohio state treasury in this fund

varied from $12,104 to $310,338.95.29

RELIEF FOR SOLDIERS' FAMILIES 103

Moved by complaints, in February 1864

the Ohio General Assembly passed

a joint resolution requesting members of

congress from Ohio "to use their

influence for the adoption of a more

safe, easy, and expeditious mode of

transmitting money by soldiers in the

army to their families and friends";

but no change was authorized by congress

during the war.30 Considering

the need for the collection of these

allotments in the field, the number of

hands through which the money had to

pass, and the paper work involved

at each stage, the transactions were

necessarily slow.31

These sums provided by the individual

soldier from his bounty money

and pay did not prove to be adequate to

take care of the financial needs of

many families left at home; too many of

them were living on marginal

incomes. The temporary business

paralysis in Cincinnati that followed the

outbreak of hostilities contributed to

the initial distress in that city, since

it reduced the possibility of wives

finding work. In 1862 the establishment

of an army clothing depot in Cincinnati,

at which seamstresses were em-

ployed, helped to give employment to

many wives and mothers of soldiers.32

But some provision was necessary to care

for needy dependents through the

first stages of the war. During this

early period the Cincinnati city authori-

ties found that their Soup House was of

great help in dealing with the

emergency.

The Soup House, located in the Medical

Institute building, had been

organized in 1860 by three

public-spirited citizens, Miles Greenwood, Ed-

ward Dexter, Jr., and D. B. Sargent, as

a pilot experiment to find an

economical way of dealing with outdoor

relief. It proved its usefulness

and was taken over by the city in June

1861.33 From that date until March

1, 1862, 3,049 families were supplied

with rations at a cost of about one-half

cent per ration. Of course, the ration

was only one-third of a loaf of bread

and a bowl of soup.34 Other

departments of the city outdoor relief distribut-

ing fuel and medicine, also showed a

great increase, which the directors

attributed to the unemployment immediately

following hostilities and "the

large number of families whose providers

have joined the army, who never

before sought relief."35

The peace-time relief services, however,

could not long take care of the

great numbers in this new class of

persons affected by the crisis. Nor did

all citizens believe that volunteers'

families should be merged in this way

with the general set of indigent

persons. Throughout the year 1861 the Cin-

cinnati City Council appropriated, in

piecemeal lots, a total of $54,366.75

for the relief of soldiers' families.36

The early regulations regarding the

distribution of city funds indicate that

the sums paid to individual families

were almost trifling. They varied from

$1.00 to $3.00 per week to each of

104 OHIO HISTORY

1,100 to 1,200 families.37 By

October 1861 it was definitely stated that

not more than $2.00 could be given to an

applicant for one week.38 After

the first eight months of the war, the

city government, except in a few crises,

permitted the county and state

authorities and private individuals to carry

the burden of family relief for

soldiers.

In the crisis produced by the outbreak

of war the Hamilton County Board

of Commissioners could not vote a levy

for this specific purpose until the

general assembly granted them the right

to do so. They were soon given

such authority. Within a month after

Fort Sumter was fired upon, the

general assembly passed an act

permitting county commissioners to levy

in 1861 a tax not to exceed one-half

mill, and to borrow in anticipation of

the receipts from that tax,39 and the

general assembly extended that authority

throughout the remaining years of the

war. The Hamilton County Board of

Commissioners promptly levied the

maximum amount for 1861.40 This levy

of one-half mill probably brought in

about $59,000 in 1861. It was not

felt necessary to make a county levy in

1862, since the state then began

its special levy for that purpose, and

it was hoped that this would be

sufficient. It did not prove to be so;

consequently, during the remaining

three years of the war a county levy for

soldiers' family relief in Hamilton

County was required in addition to the

state levy. During the crucial year

of 1864 a county levy of one mill was

assessed; for the other years it was

one-half mill. A conservative estimate

of the amount raised by county

levies in Hamilton County for this

purpose would be about $345,000 for

the war years.41

It was a cardinal principle in

nineteenth century America that poor relief

was a matter of local responsibility.

This meant that it should be locally

financed and locally administered for

local residents. In a crisis of the

magnitude of the Civil War, however,

local resources were not sufficient;

the state had to assume a share of the

burden. Professor Charles M. Rams-

dell has shown that in the Confederacy,

as long as it was expected that the

war would be a short one, provision for

the families of soldiers devolved

on the county authorities. By the end of

1862 local relief was inadequate

in most Confederate states, and during

the winter of 1862-63, the character

of relief legislation changed from local

to state and from a money tax to a

tax in kind.42 The state of

Ohio assumed responsibility for raising funds

for this purpose early in 1862, but

these funds were always locally admin-

istered for local residents. The earlier

law of May 10, 1861, already re-

ferred to, was simply permissive,

authorizing counties to levy a tax for

this specific purpose. The first state

levy was assessed by the act of Feb-

ruary 13, 1862.

RELIEF FOR SOLDIERS' FAMILIES 105

One of the members of the Ohio General

Assembly most active in

advocating state taxation for the relief

of soldiers' families was Benjamin

Eggleston, a member of the state senate

from Cincinnati. Eggleston was a

merchant and legislator who frequently

came to the help of the more un-

fortunate. In 1857 a shortage in the

supply of coal in Cincinnati produced

a severe crisis, during which the poorer

families of the city were unable

to pay the exorbitant price asked for

that scarce commodity. Eggleston,

as a member of the city council, took

the leadership in having the city buy

coal and sell it at a low price. He had

also been especially helpful to the

families of soldiers during the early

months of the war. As a member of

the upper house of the general assembly

in 1862 he helped to carry through

the first law for state relief for

them.43 By this act (February 13, 1862),

a state tax of three-fifths of one mill

was levied on the dollar valuation

of taxable property in Ohio to create a

fund "for the relief of the necessities

of the families of non-commissioned

officers, musicians and privates." It

was known as the Volunteers' Families

Relief Fund. The local assessors

were ordered to make an enumeration of

volunteers in their respective

localities and the number of dependents

in their families. Each county would

then be granted an amount in proportion

to the number of its men in the

service.44

Since the revenues from this tax would

not be received until the following

year, the county commissioners were

authorized to borrow in anticipation

of them. This the Hamilton County Board

of Commissioners proceeded to

do. They used the various war military

committees and township trustees

to investigate applicants for relief and

certify those who were in need. The

commissioners also set up a scale of

payments. A wife without dependents

would receive $2.00 every two weeks;

with one child she would receive

$2.50; with two children, $3.00; with

three or four children, $3.50; and

with five or more children, $4.00.45 For the first

payments under this new

law the Hamilton County Board of

Commissioners paid $6,212 to 2,281

necessitous soldiers' families in the

city.46

During the spring of 1862 a minor crisis

occurred in Cincinnati after

army payments fell into arrears. The

regular allotment plan was not yet in

operation and the Peninsular campaign in

the East and the Shiloh cam-

paign in the West had prevented regular

payments to the army. Also, war

casualties had increased. A crowd of

over one hundred wives, many with

children in their arms, came to the

courthouse to wait on the commissioners.

Police were summoned and the crowd

dispersed. Within the next few

months the situation worsened. Civic

leaders and philanthropists called a

public meeting "to devise means of

relief for those families of soldiers

106 OHIO HISTORY

who have not received their pay, and of

those who have lost husbands and

fathers in the service." Testimony

given at this meeting indicated that

private gifts were no longer an adequate

supplement to public relief. There

was little doubt that "large

destitution" prevailed among families of volun-

ters as well as among "'the

floating population.'"47 It was decided to under-

take a concerted effort to collect funds

from private sources, but the

threatened invasion of Ohio by the

Confederate General Kirby Smith and

the subsequent "siege of

Cincinnati" (July 1862) merged this minor

crisis into a major one for the

threatened city.

The first state levy in 1862 produced

about $510,000, with each county

receiving $6.30 for each volunteer

credited to it.48 But the number of

volunteers rapidly increased after the

law was passed, and Governor Tod,

in his message of January 5, 1863, urged

an increase of the levy to one

mill. The general assembly complied.49

The higher levy of 1863 produced

about $900,000, but the amount paid to

each county was only $5.33 for each

volunteer--almost one dollar less than

in 1862. Yet the cost of living was

rapidly rising. Both Governor Tod and

the newly inaugurated Governor

John Brough recommended an increase in

this tax for 1864. A major

portion of Governor Brough's inaugural

address dealt with this problem of

family relief. While recognizing the

great assistance given by benevolent

men and women to the suffering in their

communities, he believed that

private contributions did not properly

spread the burden. Nor did he be-

lieve that private charity was always

acceptable to recipients of this class.

"We should divest this fund of the

appellation of charity," he urged.50

The general assembly was willing to

increase the state levy for 1864 to

two mills, and it also required that

county commissioners levy an additional

amount, not to exceed one mill, if the

income from the state tax was in-

sufficient. It likewise made it possible

for cities and towns to levy still

another tax, not to exceed one-half

mill, if necessary. For those township

trustees who were recalcitrant in

granting relief to soldiers' families, this

law provided that the county

commissioners could transfer its administra-

tion to two persons appointed by them;

if the commissioners neglected to

grant relief the governor could appoint

one or more persons to administer

it.51 A new set of soldiers' families

was now included in those eligible for

relief--families of Negro soldiers, for

whom the state of Ohio had opened

volunteering in 1863. At the time Ohio

began to raise Negro regiments,

these volunteers were not eligible for a

federal bounty, and were paid only

$10 per month. Nor were their families

eligible for relief from state funds.

To meet their just claims for help,

Governor Tod had appointed a state

committee to receive private

subscriptions and distribute aid to the neces-

RELIEF FOR SOLDIERS' FAMILIES 107

sitous families of these Negro troops.52

But beginning in 1864 they were

eligible for state aid.

The year 1864 was the most difficult of

the entire war for many families

of soldiers from Ohio. In his message to

the general assembly on January 3,

1865, Governor Brough stated that the

tax levied in 1864 had proved to be

inadequate. So great was the drain on

the regular state fund during that

year, particularly for the relief of

families of the so-called Hundred Days

Men, that he found it necessary to

appropriate $5,000 from the extraordi-

nary contingent fund for this purpose.

He strongly urged that the general

assembly increase the state levy to

three mills.53 The general assembly,

however, rejected his proposal and

placed the burden of additional funds

on the local governmental units.

Counties were enabled to increase their

additional levies up to two mills, and

municipalities could increase their

levies to an additional one mill.

Families of disabled veterans were still

entitled to relief under this act. Since

the number of war widows had

increased, the law explicitly stated

that the receipt of a pension should not

exclude a war widow from the benefit of

this relief. More important, how-

ever, was the change in the method of

distribution of the funds to the

counties. Heretofore it was distributed

on the basis of the number of

soldiers enlisting from each county;

under the new act of 1865 it was to be

distributed on the basis of the number

of necessitous soldiers' families in

each county.54

During the year 1865 the state of Ohio

collected $2,137,932.69 for the

families of soldiers--the largest sum

for any one year. Since hostilities

ended in April 1865, this large amount

was not needed, and the general

assembly later transferred $800,000 to

the state sinking fund and appropri-

ated $100,000 for the state soldiers'

home. The unused balance was distrib-

uted among the several counties in the

proportion in which it was collected.55

At the close of the war the adjutant

general of Ohio reported that a grand

total of $5,618,864.89 was collected by

the state for the purpose of relief

for soldiers' families during the war

years.56 A comparison of this amount

with those collected by some of the

states of the Confederacy shows that

this was not a very large sum for the

third most populous state of the

Union. The state of North Carolina

appropriated $6,020,000 for this

purpose during the war years;57 Louisiana appropriated

$9,700,000,58

while Virginia appropriated only

$1,000,000, preferring to rely chiefly

on the system of county aid.59 In

Wisconsin the state tax brought in $2,-

545,873.78 for this purpose.60 Such

figures, however, may be misleading

in that they do not include county and

town levies, nor the important source

of private contributions.

108 OHIO HISTORY

Not even the most patriotic leaders in

the state assumed that public funds

would be more than a part of the

support for the relief of soldiers' families.

Private benevolence was expected to

supplement public support. In his

message to the general assembly in

January 1863 Governor Tod told the

members, "We are proud to know

that every neighborhood of our state is

blessed with generous and benevolent

souls."61 In 1864 Governor Brough

stated in his inaugural that "in

many counties . . . the private collections

for soldiers' families have

considerably exceeded, and in some cases doubled

the amount of the [state] tax."62 Contributions

from these generous and

benevolent persons were obtained in a

variety of ways.

One of the most important and active

agencies in Cincinnati giving aid

to soldiers' families was the

Cincinnati Relief Union. It had been organized

in 1848 with the following objectives:

to prevent vagrancy and street beg-

ging; to prevent imposition on the

benevolent; to provide work for those

who needed it; to place the youth in

schools and Sunday Schools; and to

give relief by gifts of food, clothing,

and fuel. Money was seldom given to

the recipient of its charity.63 An

annual canvass for funds was undertaken

each year; business houses and private

homes were solicited. With the

advent of the war and the needs of

soldiers' families, the union expanded

its activities. With its headquarters

at 99 West Sixth Street it had an or-

ganization to collect and distribute

funds and supplies. By the year 1862

nearly three-fourths of its cases were

families of soldiers.64 In the following

year (1863) it distributed fuel,

groceries, and clothing at the rate of nearly

$100 per day; its annual report for

that year stated that it had aided 3,400

families, of whom 2,448 were families

of soldiers.65 During the month of

January 1865--one of the most trying

months of the war--the union cared

for 2,000 families, of whom 1,500 were

those of needy soldiers.66 Its

officers and solicitors were nearly all

businessmen. One of its most active

workers in soliciting funds was C. W.

Starbuck, editor of the Cincinnati

Daily Times.67

Ward military committees likewise

solicited and distributed funds for

this purpose, in addition to securing

volunteers and bounty subscriptions.

In 1863 the eleventh ward committee in

Cincinnati gave an oyster supper

to help raise funds for the relief of its

needy families of soldiers, at which

Judge Alphonso Taft and General William

S. Rosecrans spoke.68 The

fifteenth ward committee was unusually

active in distributing about $3,000

during 1863.69 During the

holiday season of 1863 the Cincinnati branch

of the United States Sanitary

Commission sponsored its great fair for

soldiers' relief. On January 6, 1864,

there was held a grand donation ball,

and, on January 8, 1864, a grand

supper, the proceeds from both being for

RELIEF FOR SOLDIERS' FAMILIES 109

the relief of soldiers' families. About

$7,500 was raised by these events

for family relief.70

Such efforts, however, were not

sufficient for the year 1864. There were

four heavy calls for troops during that

year, including the Hundred Days

Men. During the spring and summer these

members of the national guard

from the states of Ohio, Indiana,

Illinois, Wisconsin, and Iowa were called

into active service for one hundred days

in order to release more seasoned

veterans from guarding railway lines,

garrisoning forts, and other behind-

the-lines duties. It was hoped that

these men, with those already in the field,

could supply the necessary manpower to

win the war that year. In Cincinnati

three regiments and one battalion of the

national guard were called up at

the busiest season of the year. Nearly

all of these men had dependents;

this, coupled with the suddenness of the

call and the fact that they were not

entitled to a bounty, worked a great

hardship on their families.71

In 1864 the Union armies embarked on

massive sweeping movements. In

the spring Generals Grant and Sherman

began their final grand strategy

that eventually wore out the Confederate

armies. The battles of the Wilder-

ness and Cold Harbor and the siege of

Petersburg in the Virginia theater

added to the casualty lists; Sherman's

invasion of the South and his march

to the sea culminated in the capture of

Atlanta on September 2 and Savannah

in December. Due to these extensive

campaigns of the armies, soldiers'

pay was in arrears, and allotments were

long delayed. The government

clothing depot in Cincinnati, which had

given employment to many soldiers'

wives as seamstresses, closed in 1864.72

The winter of 1864-65 was indeed

a bleak one. By November 1864 it was

estimated that 4,000 families of

soldiers were on relief in Hamilton

County.73

The necessity of securing additional

funds was understood by officials.

On November 14, 1864, Governor Brough

sent an urgent message to the

various county military committees

throughout the state calling on them to

act at once to prevent extreme hardship

among soldiers' families during that

winter. He suggested the Thanksgiving

season as an appropriate time to

seek funds, and urged rural areas to

share the burden with the towns. He

called for gifts in kind as well as in

money. Since fuel was so important,

he suggested that farmers bring in

supplies of wood as well as part of their

garden produce from the previous summer.

"I do not ask charity for the

families of these men," he wrote,

"I ask open manifestations of gratitude."74

Spurred by the urgency of the local

situation and the official appeal of

the governor, the Hamilton County

Military Committee called a public

meeting to make plans for meeting the

emergency. It was determined to

undertake a city-wide solicitation of

funds. All organizations in the city

110 OHIO HISTORY

were encouraged to contribute, and the

various churches were asked to

send ladies to a general meeting to plan

their part of the drive.75 The ladies,

remembering the success of the sanitary

fair held during the previous year,

which had netted $235,000, decided to

undertake a similar project for the

families of soldiers but on a somewhat

more modest scale.76 In addition

to the fair, there was a series of

entertainments, both social and dramatic.

The entire project was known as the

Testimonial to Soldiers' Families.

The first event was held at Wood's

Theater on December 12, with a

benefit performance of the drama,

"All That Glitters Is Not Gold; or the

Factory Girl's Diary."77 The

Union Dramatic Association of amateurs

staged an entertainment at the residence

of Judge James Hall, consisting of

two short plays, "A Pretty Piece of

Business" and "Box and Cox," which

the newspapers reported as being

"both piquant and spicy." This effort of

the amateurs netted $300.78 At the other

end of the cultural spectrum was

a recital of sacred music at the Seventh

Presbyterian Church, which brought

in $335.79 Among the last events was a

great amateur performance of

Shakespeare's Hamlet at Pike's

Opera House, in which Lieutenant Governor

Charles Anderson took the leading role

and Thomas Buchanan Read recited

the prologue. This affair netted

$5,227.30.80

It was the fair, however, which occupied

the center of public attention.

It was housed in a large four-story

building at 94 West Fourth Street.

General Joseph Hooker, who was stationed

in Cincinnati in command of

the northern department of the army, was

the honorary president. He

visited the fair each day and evening. Other

military leaders who were

in the city, such as General William S.

Rosecrans and General August T.

Willich, also paid visits. At various

booths were sold all manner of articles

and refreshments; Christmas trees, with

their decorations, were sold in

large numbers; and the floral displays

were unusual. There was a fish

pond and a post office. At the latter,

the reporter for the Cincinnati Gazette

wrote, "was a circle of young

ladies, . . . [and] the fact that their own

tapering fingers write the pretty

nothings they give to any who may call . . .

combined with . . . their own wit, . . .

does not constitute the least attractive

feature of the elegant establishment."81

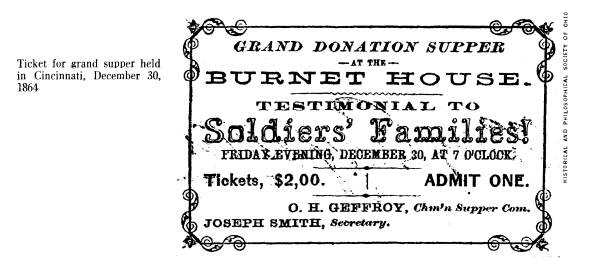

The fair closed with an elaborate

grand supper and ball held at the Burnet

House on the evening of December

30, at which it was claimed 4,000

persons were fed by "ladies of the elite

of the first social circles of the city,

in elegant toilettes." The families of

the soldiers were served a New Year's

dinner on December 31 from the food

remaining.82

Although reports on gifts and proceeds

were published almost daily in

the local newspapers, a final report

cannot be found. Some contributions

|

RELIEF FOR SOLDIERS' FAMILIES 111 were being received as late as March 1865. The money in hand, however, was distributed at once. On February 28, 1865, the fourth installment of $10,000 was distributed to families--a total of $40,000 up to that time.83 It is probable that about $50,000 was earned from all of the events and solicitations comprising this testimonial. The sanitary fair of the preceding year and this Testimonial to Soldiers' Families were the most strikingly dramatic and colorful episodes in the war-time life of Cincinnati. Butler County, Ohio, had staged a similar event at its county seat, Hamilton, in 1863, at which $9,600 was received,84 and it is probable that other cities and towns had similar events throughout the war for this purpose. They offered a constructive outlet for popular support and an escape from war- time tensions, particularly for women. They were also dramatic reminders that the needs of the families of soldiers were on the public conscience. In the case of the Cincinnati testimonial, it provided a boost needed to carry on relief during the remainder of the stark winter of 1864-65. |

|

|

|

For the number of soldiers' families receiving relief in Ohio during the war, accurate figures are not available. The ratio at which officials at Columbus estimated the number of necessitous families during 1862 and 1863 was one of every four.85 The enumeration made by assessors in 1865 indicated that there were 44,090 families of soldiers in the state at that time, of which 37,118 were necessitous. These necessitous families in 1865 included 121,923 persons.86 This represents a sharp rise in necessitous families during the war from twenty-five percent to eighty-four percent. This was due to the casualties over the war years, the prolonged absence of |

112 OHIO HISTORY

soldiers in the field, and the sharp

rise in the cost of living. The change in

the law in 1865 by which counties

received state funds in proportion to the

necessitous families within the county

also probably led to more liberal

standards of need.

It was probably inevitable that charges

would be made of political parti-

sanship in local administration of this

type of relief. This was true in

Ohio in 1863 and 1864 during the heat of

the state and national election

campaigns. In April 1864 Governor Brough

asserted that there "were almost

daily complaints" of townships

trustees in certain localities--that women

were rudely treated by the local

officials when they sought relief; that they

were compelled to travel distances to

obtain signatures for papers, causing

considerable inconvenience; or that they

were "insultingly catechised" as

to their means of support. "I am

mortified that these things are so," he

wrote to the county military committees

in urging them to investigate such

complaints. In a few extreme cases it

was found that the relief funds had

been diverted to bridge funds and other

local projects.87 In his message to

the general assembly Governor Brough

later stated that recalcitrant trustees

had not so much refused to conform to

the law as they were dilatory in

granting relief; that it was their

manner rather than their denial of relief

that was objected to.88

The end of the war in April 1865 and the

rapid demobilization consider-

ably lessened the problem of family

relief. There were still the war

casualties to be helped--the orphans,

widows, and disabled soldiers, many

of whom had families. The Ohio Volunteer

Family Relief had provided a

transitional form of relief for this set

of needy casualties, and, before the

end of the war, plans were already in

operation for more adequate means of

help for them. The federal government

would undertake a major part of

this relief through its pension system,

the soldiers' homes, and other

methods. Except in occasional times of

local disaster, it is probable that

this relief for soldiers' families

during the Civil War was more extensive

and continued longer than any other type

of relief in the state before that

time.

THE AUTHOR: Joseph E. Holliday is assist-

ant dean of the college of arts and

sciences and

professor of history at the University

of Cin-

cinnati.