Ohio History Journal

|

HARLEY J. McKEE

Original Bridges on the National Road in Eastern Ohio

The approach to this subject is purely descriptive and is based on observations made during 1971 while the author was inspecting structures which had been recorded by the Historic American Buildings Survey.1 Among the records in question were a number of photographs of bridges on the old National Road taken late in 1933, for which the locations had not been as clearly given as HABS standards require. A part of the assignment was to determine which of the bridges, if any, were still in existence and to note their precise location. The search took several days of driving along a ninety-mile stretch of the road, uncounted hours of map study, and some |

|

1. This paper was originally presented at the First Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial Archaeology, Cooper Union, New York City, April 8, 1972.

Mr. McKee is Professor Emeritus of Architecture, Syracuse University. |

|

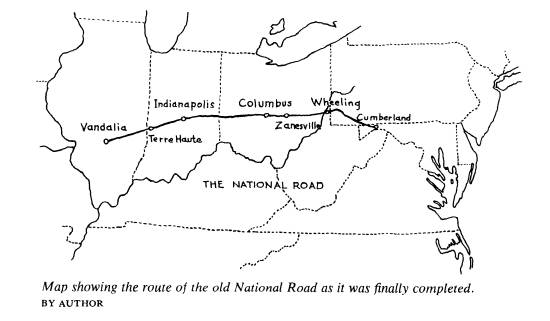

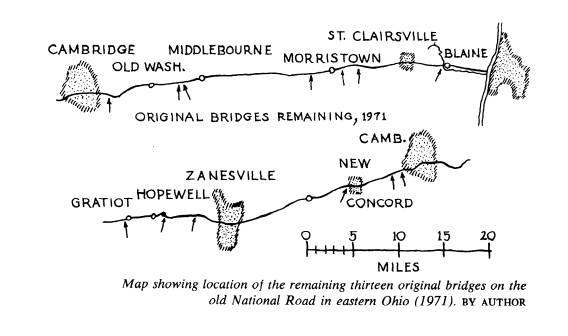

other inquiries. In retrospect it seems that most of the time was spent in learning how to look. The Cumberland Road, old National Road, or National Pike was authorized by Congress in 1806. Construction was begun in 1811, and by 1818 the road was com- pleted as far west as Wheeling, West Virginia. The portion in eastern Ohio was built during the late 1820's and early 1830's. It reached Zanesville in 1829. As construction proceeded westward from there toward the proposed terminal at Jefferson City, Missouri, the midwestern states assumed responsibility for road building. The Na- tional Road, therefore, was not continued beyond Vandalia, Illinois. After railroads began to serve this region, traffic on the government road declined. In 1853 admin- istration was turned over to the individual states and maintenance then varied from place to place. With the coming of automobiles this old route regained much of its former im- portance. Norris F. Schneider2 has written about the paving of an experimental 24- mile section west of Zanesville in 1914 and 1915. This 16-foot wide strip of concrete followed the original road bed and utilized the old bridges. In the late 1930's the route which we know as US-40 was again improved, the work destroying a number of the original bridges. In the 1950's much of US-40 was widened to four lanes and other improvements were made. In the mid-1960's Interstate 70 was begun. All of these highways took the same general route but in the hilly terrain of eastern Ohio modern standards demanded straightening, reducing gradients and, most recently, building interchanges and ramps to stretches of high-speed limited-access ways. Various short sections of the older road were bypassed and allowed to revert to strictly local use, which in some cases is very light. At such places are found the remaining original bridges, thirteen in all. These are all located between Blaine and Gratiot;

2. The Times Recorder (Zanesville), April 24, May 1, 1966. See also Wayne E. Fuller, "The Ohio Road Experiment, 1913-1916," Ohio History, LXXIV (1965), 13-28. |

|

Original Bridges 133

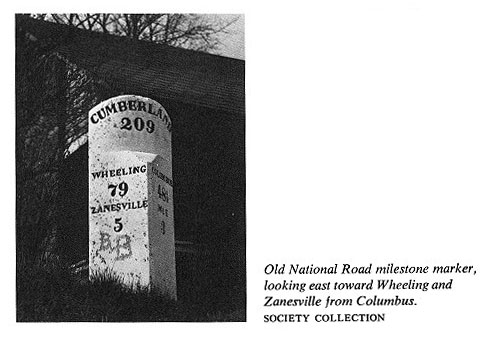

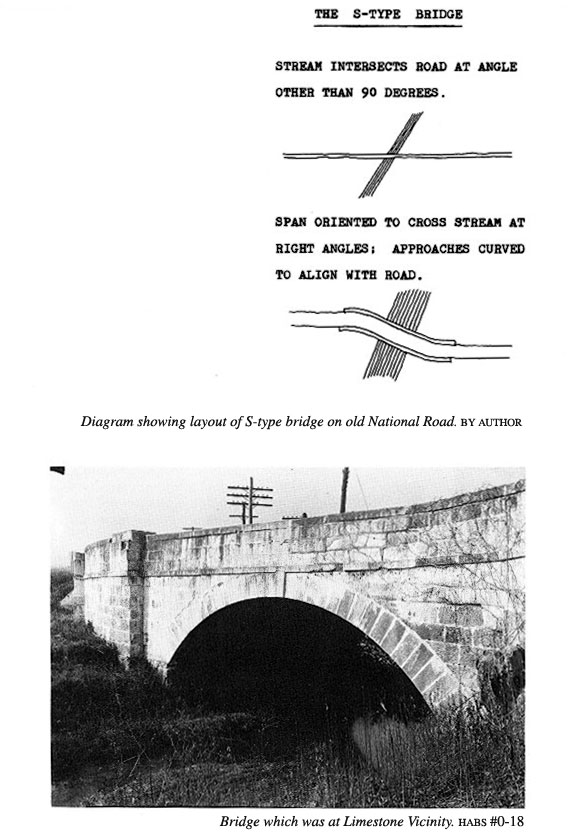

west of there the terrain is mostly so level that the widened US-40 exactly follows the line of the old road. The old roadway can be traced on 15-minute quadrangles of the United States Geological Survey, which for this particular area are available for dates varying from 1903 to 1909. Comparison with 71/2-minute quadrangles made in 1960 and 1961 shows where the improved highway exactly coincides with the old one and where the course has been changed. Additional evidence that one is on the old National Road is afforded in places by the milestones which remain. These are in the form of square prisms set diagonally, the upper part of one corner being rounded and inscribed with the distance from Cumberland. Below this, on the two visible plane faces, are shown the distances to nearer points, so placed that the traveler first notices the name of the city toward which he is going. The bridges which remain were all built of sandstone. Deposits of this material, formed during the Pennsylvanian Period, roughly 250 million years ago, are ex- tensive in the three counties traversed by this part of the road--Belmont, Guernsey, and Muskingum--and were quarried in the nineteenth century.3 With a few ex- ceptions this sandstone has endured very well. Five bridges that are still standing are of the so-called S-type. Various extravagant stories have been told about why bridges were laid out on the plan of an S-curve. Such anecdotes seem more interesting than the truth, so they have persisted. Any civil engineer, however, knows that it is desirable to avoid obstructing the flow of a stream and to employ a straight masonry arch of minimum span. This must be at right angles to the stream. When the road lies at a different angle the approaches can be curved to bring the two into alignment. The resulting S-curve plan was hardly a |

|

3. J. A. Bownocker, Building Stones of Ohio, Bulletin 18, Geological Survey of Ohio, Fourth Series (Columbus, 1915). |

|

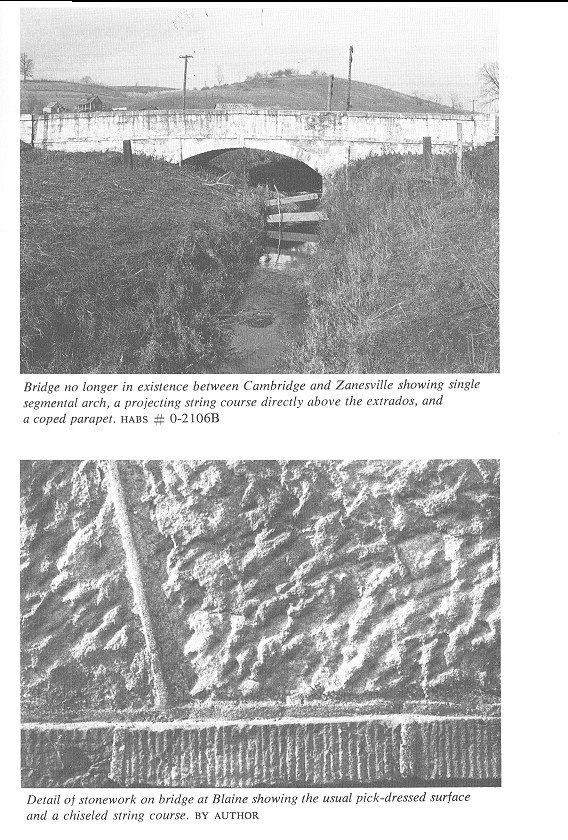

136 OHIO HISTORY

hazard to vehicles drawn by horses and oxen, but when automobiles became common, road improvements either bypassed or replaced the S-bridges, as they did other sharp curves in the highway. A bridge at Limestone Vicinity, no longer in existence, illustrates such a plan. The arched portion is straight and the end portions curve in opposite directions. At the inside curve, part of the parapet is supported above a straight spandrel wall by means of corbeling. The bridges in eastern Ohio consisted typically of a single segmental arch, a pro- jecting string course directly above the extrados, and a coped parapet. One which used to be somewhere between Cambridge and Zanesville was quite low and did not need buttresses. A picture taken in 1933 also shows fairly representative terrain. This bridge had carefully dressed regular stonework on the intrados, arch, and outer wall. The abutment facing the water, however, was randomly laid. As a rule, ordinary stones were dressed with a pick and the trim stones were given a hammered or chiseled finish. A detail from the bridge at Blaine illustrates the usual pick-dressed surface of the wall and a chiseled string course. The joints here are wider than usual. Most would not exceed one quarter of an inch, although in the repointing process mortar has often been smeared about and the appearance has been coarsened. In general, all of these bridges are constructed of large stones. Courses are one foot or more in height and individual stones average three feet in length on the face. One can assume that each weighs between 500 and 1000 pounds. Arch voussoirs are from 15 to 18 inches in depth and carefully dressed and fitted. Mortar is scarcely needed for structural stability, but is probably necessary to keep water out of the joints, in this climate. The ancient Romans built some arched structures of large stones without mortar, which are in good condition today. |

|

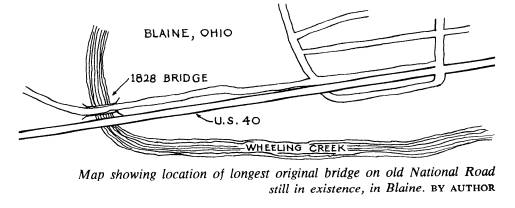

Going west from the Ohio River, the first original bridge one encounters is at Wheel- ing Creek, at the western edge of Blaine. It was retired from highway use about 1933, when a much longer and higher concrete structure was completed alongside, at the beginning of a 500-foot climb out of the creek valley. The 1828 bridge is the longest of those remaining from the old National Road: 345 feet. It has three segmental arches of 25-foot, 40-foot, and 50-foot spans, respectively, although when seen in perspective, looking west, they may appear equal. The width between parapets is 25 feet. The approaches are curved. Above each pier there is a rounded buttress with a |

|

Original Bridges 139

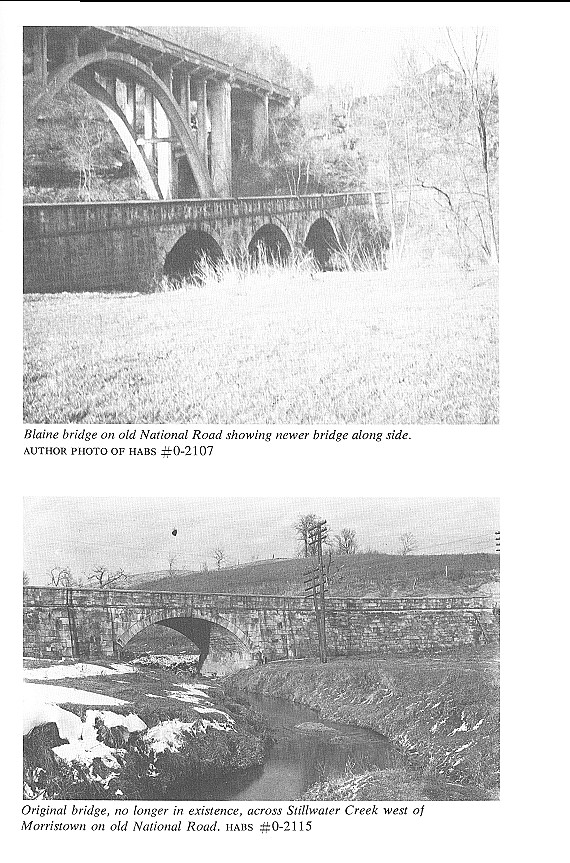

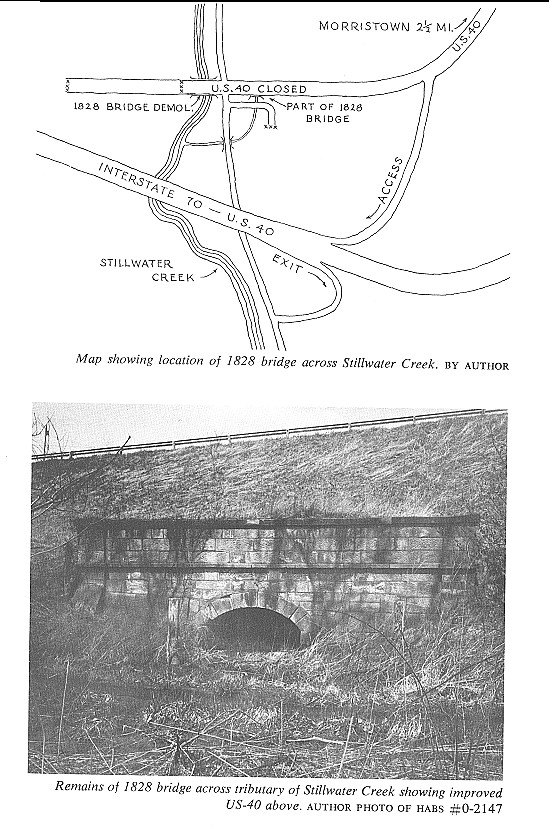

large moulded base. In 1933 there was still a cylindrical milestone at the top of one buttress but it is no longer there. On the inside of the parapet there is an inscribed stone panel bearing the date 1828, but earth and paving now cover the lower part of the panel. About four miles west of St. Clairsville, on Belmont County 40-B just east of Lloydsville, there is a small bridge across a tributary of Wheeling Creek. A single arch of 12-foot span has rusticated bevel-jointed voussoirs and a projecting keystone. These features, as well as the pick-dressed sandstone walls, are quite typical. The parapet slopes upward slightly toward the east end to conform with the grade of the road; this slope is effected by one tapering course of stone just below the parapet. A similar bridge of the same size remains at Barkcamp Creek, one mile east of Morris- town. To see it one must look down along the north side of the fill on which US-40 has been elevated, or pull off onto the old bypassed section of the road. The bridge across Stillwater Creek, about three miles west of Morristown, was demolished and replaced by a new one, probably around 1939. Recent road con- struction at this site has changed the drainage pattern somewhat. (The accompany- ing map, although not very accurate, shows the layout.) A small tributary of Still- water Creek which flowed down from the northeast was crossed by the original Na- tional Road; that bridge is still in existence but it is nearly covered by earth fill. Only the southern face remains exposed. It is 32 feet long and the arch has an 8-foot span. Here one can see the difference in levels between the original road and the improved US-40, which has itself been closed off since the construction of 1-70. |

|

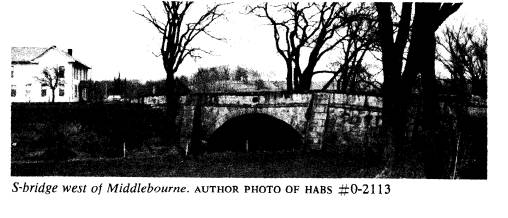

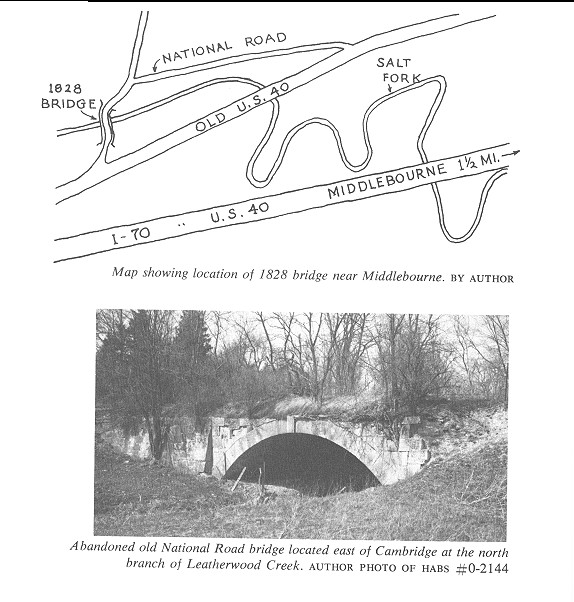

Two miles west of Middlebourne the old road crossed Salt Fork on an S-bridge 185 feet long overall, with a single segmental arch spanning 40 feet. The crown has settled somewhat although the masonry is otherwise in reasonably sound condition, and the highway department has posted a 5-ton load limit. The abutment walls are battered and buttressed. This bridge has been bypassed twice and now appears to serve a couple of farms, although it is not their only means of access. A historical marker was erected here in 1954 by the Ohio Society of Professional Engineers, who have done their best to inform visitors of the reasons for an S-plan. A short distance farther west there is a small bridge of 12-foot span over a tributary of Salt Fork. There the old National Road has become a local way connecting Old Washington and Middlebourne, while the combined 1-70 and US-40 passes alongside. |

|

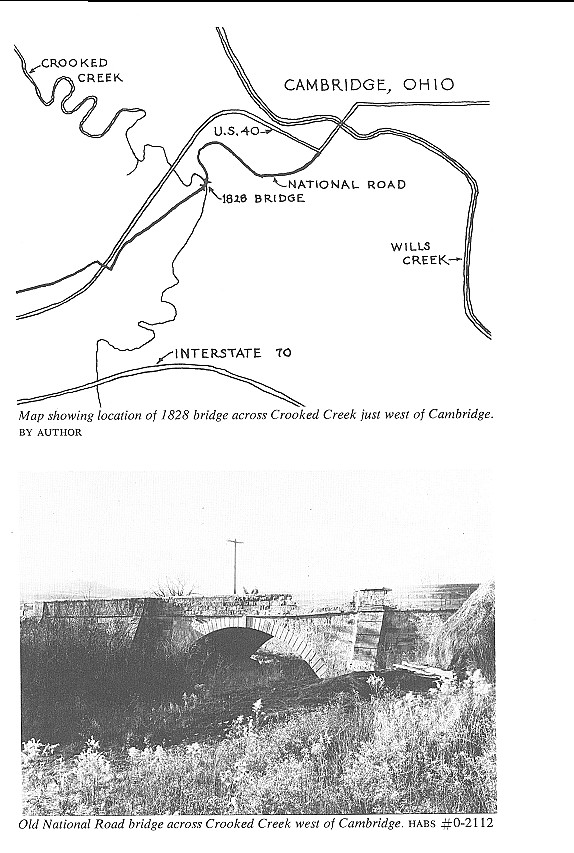

Just east of Cambridge, at the north branch of Leatherwood Creek, there is a bridge which has been abandoned for many years. The 30-foot arch appears to be sound but the parapets have disappeared and the eastern approach is disintegrating. The western end is partially buried under earth fill for Guernsey County 40-A. Both ap- proaches are curved. A bridge at the western edge of Cambridge lies at the base of a steep ridge 200 feet high between Crooked Creek, which it crosses, and Wills Creek. The old road took a sharp turn left, went around one end of the hill in climbing 100 feet, and entered the city. US-40 was placed further north, taking a wider turn around the ridge through a cut to reduce the grade. I-70, recently constructed, bypasses the city on the south. Here we can see how roads were laid out at three different epochs. The bridge has a single segmental arch of 45-foot span and a total length of 180 feet. It is buttressed. The parapet on the southeast side had been repaired with |

|

142 OHIO HISTORY

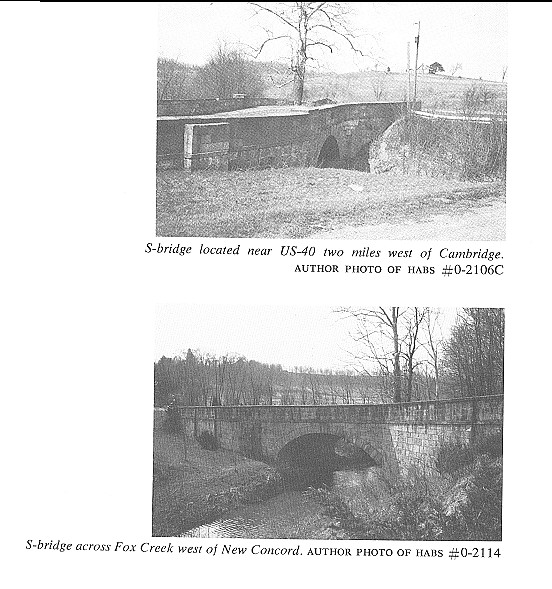

concrete before 1933, when this photograph was taken. One might suspect that a vehicle coming downhill too fast had failed to make the turn successfully and damaged the parapet. On both sides there are regular courses of stonework, rusticated buttress- ing and battered abutment walls. Here, as on some other bridges, the parapet is in- clined to follow the grade of the road, and the coursing of the walls below it is level. The width between parapets over the arch is 27 feet, and about two feet more at the ends. Each stone course is one foot high. On the parapet there is a tablet having an arched head and a hood, but unfortunately the inscription is badly weathered and illegible. At the far end the road turns sharply to the left. Two miles west of Cambridge, straightening of the highway has left a small road- side area, in which stands one of the original S-bridges. In plain view from US-40, with a historical marker erected by the Ohio Society of Professional Engineers, this |

|

Original Bridges 143

is one of the two best-known bridges remaining from the National Road. The arch spans 30 feet and the total length is 120 feet. Frost action has caused some of the stone courses to shift slightly along their horizontal beds, but aside from this the masonry is in good condition. The second plainly visible and therefore well-known old S-bridge is located at Fox Creek, just west of New Concord. It, too, has been marked by the O.S.P.E. This structure stands in a small roadside park. The arch has a span of 30 feet, the internal width is 26 feet, and the total length is 140 feet. Anyone following US-40 and 22 can find it. Some two miles west of Zanesville, where a bypassed section of the National Road now provides access to a scattering of suburban houses, there is an original bridge of considerable interest because of its well-preserved panel inscribed with the name of the builder, John Carnahen, the date, 1830, and Masonic symbols. This bridge is a short distance west of Cumberland milestone 207. It crosses a branch of Timber Run with a single 12-foot arch. This structure is unusual in not having a string course at the road level, but at this point one can see a tapering stone course which conforms to the grade. One of the most picturesque remaining bridges is located some seven miles west of Zanesville, on a short abandoned section of road just north of US-40 at the eastern edge of Mt. Sterling. Screened by trees and undergrowth, this structure now serves as a dam to impound the water of a miniature lake. On the inner side of the north parapet there is a panel bearing the inscription "Rebuilt in 1915." Observation of the masonry, which is in good condition, leads one to believe that the so-called rebuilding consisted only of nominal repairs and paving. The arch is semicircular and about 20 feet in span. Just west of Gratiot, on the road which continues its main street, an original bridge |

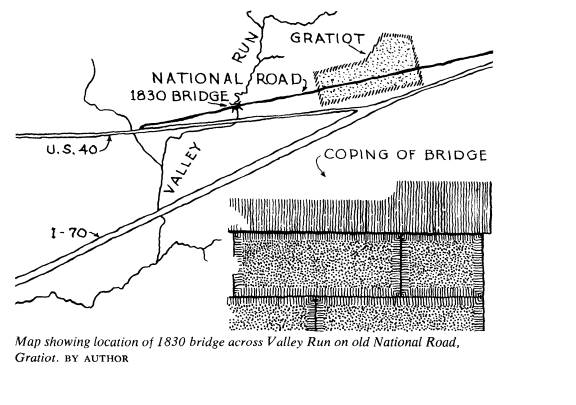

144 OHIO HISTORY

crosses Valley Run. It and the village

have been bypassed by US-40 and I-70. This

bridge has several interesting features,

especially the terminal stones of the coping,

which are shaped to serve as finials. On

the inner side the parapets have a bush-

hammered finish, the points of the

hammer being four-tenths of an inch apart. The

margins were drafted with a chisel.

Hammered finishes of the same degree of fine-

ness, or coarsesness, can be seen on

various other Ohio structures, such as the

Richardson House at McConnelsville,

built in 1838.

The bridge is 72 feet long and has a

single segmental arch of 27-foot span. The

parapet is cambered, rising about four

or five inches at the center. This was accom-

plished by a corresponding variation in

the height of a stone course just below the

parapet. This feature is a refinement of

line--a refinement consistent with the ex-

cellence of craftsmanship otherwise

displayed.