Ohio History Journal

JEFFREY P. BROWN

Chillicothe's Elite: Leadership

in a Frontier Community

The Northwest Territory was dominated by

its small urban com-

munities, even though most settlers were

farmers. The towns became

crucial regional centers for business,

politics, and cultural affairs.

They served as headquarters for wealthy

and powerful merchants,

provided a base for lawyer-politicians,

and often contained the

homes of prominent rural landowners. A

few of the Northwest's

towns eventually grew into great

metropolitan centers, but most sim-

ply remained important regional centers,

with thousands rather than

millions of residents. Chillicothe,

Ohio, the economic and political

hub of the lower Scioto Valley, serves

as a good paradigm for these

towns.

Historians have debated for generations

the degree to which pio-

neer societies represented advancing

democracy. Classic historians

like Frederick Jackson Turner argued

that the frontier reduced social

elites and deference. Since the 1940s,

however, most frontier histori-

ans have emphasized the social and

economic competition that de-

veloped in pioneer communities. Thus,

Richard C. Wade argued

both that urban centers were crucial

parts of the Ohio Valley fron-

tier, and that they quickly produced

social elites. Wade stressed that

these elites, cooperating in business

and educating their children in

elite school settings, soon formed tight

inner circles that were nearly

closed castes. Stanley Elkins and Eric

McKitrick emphasized that lo-

cal rivals for social prominence often

learned to work together, but

only to advance their town's fortunes

against rival towns. Don H.

Doyle and other historians stress the

conflict that emerged within

towns, where continued in-migration

inevitably produced social cha-

os and conflict. Robert Wiebe reminds us

that it took time for the

leaders of isolated communities to build

ties to one another, while

Edward Pessen and Frederick Jaher remind

us that nearly all Ameri-

can communities, even the newest,

quickly produced social and eco-

Jeffrey P. Brown is Assistant Professor

of History at New Mexico State University.

Chillicothe's Elite

141

nomic elites. Certainly frontiers like

the Shenandoah Valley, as Rob-

ert Mitchell observes, developed both

social stratification and

dominant towns.1

Historians of the Northwest frontier

have generally found much

the same process of elite development.

To be sure, Ohio and other

Northwestern communities did not produce

plantation cultures,

which automatically meant an upper class

ruling a lower class of

slaves. Yet Wade, Andrew R.L. Cayton,

Alfred B. Sears, Jeffrey P.

Brown, and other researchers emphasize

that most of Ohio's regions

were dominated by appointed or

transplanted elites, and that men

who were not part of an early inner

circle met much resistance as they

tried to advance their own fortunes.2

It is therefore important that we

look at early communities like

Chillicothe, both to see the nature of

their leaders and the degree to which

elite control shaped communi-

ty destiny.

Chillicothe was first and foremost a

river town. The Scioto River,

which courses through central Ohio to

the Ohio River, offered pio-

neers easy access to the interior.

Although the Scioto Valley was

hilly and somewhat less fertile than

other parts of Ohio, it easily sup-

ported the classic frontier

triumvirate-corn, cattle, and hogs. The

area that became Chillicothe, encircled

by Paint Creek and the curl-

ing Scioto, had enough elevation to

avoid most floods. Ebenezer

Zane's trace road across southeastern Ohio

met the Scioto at this

1. The debate over frontier and national

social systems is enormous. See among oth-

ers Ray Allen Billington, ed., Frontier

and Sections; Selected Essays of Frederick

Jackson Turner (Englewood Cliffs, 1961, 37-97; Richard C. Wade, The

Urban Frontier;

Pioneer Life in Early Pittsburgh,

Cincinnati, Lexington, Louisville, and St. Louis (Chi-

cago, 1971 edition); Stanley Elkins and

Eric McKitrick, "A Meaning for Turner's Fron-

tier, Part I: Democracy in the Old

Northwest," Political Science Quarterly, 69 (Septem-

ber, 1954), 321-53; Don H. Doyle, The

Social Order of a Frontier Community:

Jacksonville, Illinois, 1825-1870 (Urbana, 1978); John W. Reps, Town Planning in Fron-

tier America (Princeton, N.J., 1965; reprint ed., Columbia, Mo.,

1980), 181-210; Robert

Wiebe, The Opening of American

Society: From the Adoption of the Constitution to the

Eve of Disunion (New York, 1984); Edward Pessen, Riches, Class, and

Power Before the

Civil War (Lexington, Mass, 1973); Frederick Cople Jaher, The

Urban Establishment:

Upper Strata in Boston, New York,

Charleston, Chicago, and Los Angeles (Urbana,

1982); and Robert D. Mitchell, Commercialism

and Frontier: Perspectives on the Early

Shenandoah Valley (Charlottesville, 1977).

2. John D. Barnhart, Valley of

Democracy: The Frontier Versus the Plantation in the

Ohio Valley, 1775-1818 (Lincoln, Nebr., 1953); Wade, Urban Frontier; Alfred

B. Sears,

Thomas Worthington-Father of Ohio

Statehood (Columbus, 1958); Andrew

R.L.

Cayton, The Frontier Republic:

Ideology and Politics in the Ohio Country, 1780-1825

(Kent, 1986); Goodwin Berquist and Paul

C. Bowers, The New Eden: James Kilbourne

and the Development of Ohio (Lanham, Md., 1983); and Jeffrey P. Brown, "Samuel

Huntington-A Connecticut Aristocrat on

the Ohio Frontier," Ohio History, 89 (Au-

tumn, 1980).

142 OHIO HISTORY

point. Chillicothe was thus well served

by both water and land

transportation.3

Although Chillicothe lay in a fertile

and accessible valley, it was

for many years barred to white

settlement by Ohio's Indians. Their

defense of their homelands, successful

in the 1780s and early 1790s,

ended after Anthony Wayne's partial

victory in 1794. The Treaty of

Greenville, signed in 1795, established

a new settlement border some

eighty-five miles north of the

Chillicothe region. This immediately

made the Scioto-Paint intersection the

heart of an open and fertile re-

gion.4

Chillicothe's development was crucially

shaped by both the Indi-

an resistance, which delayed settlement

during the squatter period

of the 1780s, and by governmental

agreements on land. The federal

government owned the eastern side of the

Scioto, and therefore

controlled surveys and sales. To the

west, however, the Valley lay

within Virginia's Military District, an

area reserved for Virginia's Rev-

olutionary veterans with state land

warrants. Most veterans sold their

claims to speculators who, in turn,

hired agents and surveyors to lo-

cate and sell or rent their holdings.

These men were often paid with a

portion of the lands they handled. While

speculators usually stayed

on the seacoast, their resident agents

and surveyors set up headquar-

ters and homes in Chillicothe. This was

a common frontier pattern,

as Thomas Slaughter has demonstrated in

his study of contemporary

west Pennsylvania. The Scioto Valley,

like other frontiers, had ac-

quired an instant social and economic

elite.5

During the 1780s, Virginians with land

warrants headed first to

state-owned lands in Kentucky. Fertile

soil, and relatively safer settle-

ment, made Kentucky more attractive than

the Northwest Territory.

Only the most daring surveyors and

speculators began to explore up

the Scioto, an area still controlled by

hostile Indian nations. As al-

ways, the surveyors, led by men like

Nathaniel Massie, reserved the

best claims for themselves. They were

thus in a prime position to

prosper when settlement began to follow

them up the Valley. Massie

and other surveyors tried to lay out

entire future towns, since this

3. John G. Clark, The Grain Trade in

the Old Northwest (Westport, 1966), 3-4; Ran-

dolph C. Downes, Frontier Ohio,

1778-1803 (Columbus, 1935), 71, 80; and Robert E.

Chaddock, "Ohio Before 1850: A

Study of the Early Influence of Pennsylvanian and

Southern Populations in Ohio,"

Ph.D. thesis, Ohio State University, 1908, 17.

4. Wiley Sword, President

Washington's Indian War; The Struggle for the Old North-

west, 1790-1795 (Norman, Okla., 1985); and Richard H. Kohn, Eagle

and Sword; The

Federalists and the Creation of the

Military Establishment in America (New York, 1975).

5. Thomas P. Slaughter, The Whiskey

Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American

Revolution (New York, 1986), 65, 82-88.

Chillicothe's Elite

143

made their landholdings much more

valuable. After the Treaty of

Greenville opened up Scioto settlement,

Massie founded the town of

Chillicothe on 3,000 acres he had

located between the Scioto and

the Paint. He divided his town into 287

inlots, and like many town

promoters offered free inlots and

outlots to the first hundred settlers.

Later settlers had to pay $10 for each

lot. Most of Massie's early resi-

dents came with a group of anti-slavery

Kentuckians led upriver by

the Reverend Robert Finley, who

demonstrated his own anti-slavery

commitment by freeing his slaves before

leaving Kentucky.6

Chillicothe quickly became the most

important community in the

Valley. Northwest Territory officials

made it the seat of Ross County,

a newly created jurisdiction.

Chillicothe also became the federal

land office for government lands sold

east of the Scioto. The Valley

grew rapidly, and by 1801 it held almost

12,000 residents, about a

fourth of the white settlers in the

Northwest. Ambitious speculators

and surveyors enjoyed rapid land sales

or rentals.7

Some of the Scioto's landowners and

political leaders were self-

made men who found that enduring the

risks of wartime surveying

brought them their one chance for wealth

or political respect. Dun-

can McArthur, the son of a poor upstate

New York family, and Elias

Langham, an ordinary Virginian who

became a Revolutionary artil-

lery lieutenant, both prospered through

their willingness to work in a

dangerous profession. Another surveyor,

John McDonald, came from

a poor backcountry Pennsylvania family,

but eventually acquired

land, became a justice of the peace, and

won military honors. How-

ever, other surveyors came from

well-to-do backgrounds. Nathaniel

and Henry Massie, for example, were the

sons of a substantial

Virginia planter with large Western land

claims. Massie's appointment

as Deputy Surveyor for the Virginia

Military District stemmed partly

from his connections, although like

McArthur and Langham he

risked his life in a dangerous venture.8

The early surveyors, like

6. William Thomas Hutchinson, "The

Bounty Lands of the American Revolution in

Ohio," Ph.D. thesis, University of

Chicago, 1927, 36-52; John McDonald, Biographi-

cal Sketches of General Nathaniel

Massie, General Duncan McArthur, Captain William

Wells, and General Simon Kenton (Dayton, 1852), 57-65; Henry H. Bennett, The County

of Ross ... (Madison, 1902), 49-53; and David Meade Massie, Nathaniel

Massie, A Pi-

oneer of Ohio, A Sketch of His Life

and Relations From His Correspondence (Cincinna-

ti, 1896), 14-52.

7. John Steele, Schedule of July 4,

1801, Cincinnati Historical Society. Early settlers

in Ross County wanted to name it Massie

County.

8. Massie, Massie; Isaac J.

Finley and Rufus Putnam, Pioneer Record and Reminis-

cences of the Early Settlers and

Settlement of Ross County, Ohio (Cincinnati,

1871), 134;

Nelson W. Evans, A History of Scioto

County, Ohio (Portsmouth, 1903) 2 Vols., 2:209;

Lyle S. Evans, A Standard History of

Ross County, Ohio . . . (Chicago, 1917), 2 Vols.,

144 OHIO HISTORY

Massie or McArthur, were soon joined by

a second wave of well-to-

do Virginians. These men bought land

warrents through agents at

home, and expanded their Scioto

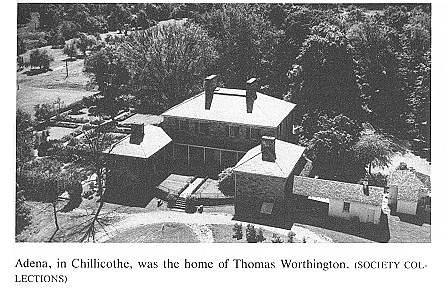

holdings. Thomas Worthington,

one of the most prominent early

landowners, typified these investors.

Worthington, a planter's son, came West

originally as an agent and

land locator for a family friend. He

liked the area and built an estate

there, stocking it with his former

slaves as tenant farmers. Yet Wor-

thington's 18,273 acre holding was

relatively modest. Nathaniel and

Henry Massie acquired at least 123,000

acres in the Military District,

while Duncan McArthur claimed another

90,000. Cadwallader

Wallace acquired over 118,000 acres, as

did a Kentuckian named

Taylor. Lucas Sullivant picked up 49,000

acres. Most of the great land

barons lived near Chillicothe, or hired

local agents to oversee their

domains, but some, like William Lytle of

the Cincinnati region, oper-

ated from nearby parts of the Northwest.

Among these large-scale

landowners, Worthington's holdings were

only the eighteenth in

size!9

Chillicothe rapidly became a thriving

governmental center and

business community. Many of the more

successful landowners used

their profits or resources to open other

enterprises. Nathaniel Massie

became a local agent for Richmond

speculators, paying their taxes

and advising them when to buy, sell, or

rent land. He founded a

number of other speculative towns,

developed an iron furnace on

Paint Creek, and speculated in salt with

James Wilkinson of Ken-

tucky. Land locater Joseph Kerr of

Pennsylvania, one of Massie's as-

sistant surveyors, opened a

slaughterhouse and pork salting estab-

lishment, and by 1804 began shipping

farm produce down the rivers

to New Orleans.10 Thomas

Worthington built a business empire out

of Chillicothe. He worked as an agent

for many absentee landowners,

including Albert Gallatin and Bailey

Washington. Worthington built

a series of sawmills and gristmills,

leasing them to their managers. He

constructed roads, erected a ropewalk

and a cloth mill, imported cat-

tle from the Chickasaw nation, and

raised extensive sheep herds.11

1:237-244; and Francis Heitman, Historical

Register of Officers of the Continental Army

(Baltimore, 1967), 340.

9. Hutchinson, "Bounty Lands,"

196-97; McDonald, Sketches, 93-94; Ellen S.

Wilson, "Speculators and Land

Development in the Virginia Military Tract: The Terri-

torial Period," Ph.D. thesis, Miami

University of Ohio, 1982, 7, 56-66, 103, 110; Sears,

Thomas Worthington, 14-19; The Ohio Historical Society, The Governors of

Ohio (Co-

lumbus, 1954), 31-34; Malcolm J.

Rohrbaugh, The Land Office Business; The Settle-

ment and Administration of American Public Lands,

1789-1837 (London, England,

1968), 43-47, 69, 171; and Nelson Evans,

Scioto County, 2:209.

10. Lyle Evans, Ross County, 1:223-226;

and Marie Dickore, ed., George P. Carrel,

General Joseph Kerr ... "Ohio's

Lost Senator" (Oxford, Ohio,

1941), 5-8.

11. Sears, Thomas Worthington, 25-36,

214-15.

|

Chillicothe's Elite 145 |

|

|

|

Other men, while not huge landholders, also developed important local businesses. Felix and George Renick, members of a large clan from the South Branch of the Potomac, became major cattle dealers. They bought cattle from relatives in western Virginia and Kentucky, and as early as 1804 began leading cattle drives to Eastern cities like Baltimore and Philadelphia.12 By 1807, travelers noted that Chilli- cothe possessed six taverns and fourteen general stores. The town soon included several tanneries, two hat makers, two brewers, sever- al cotton mills, and a paper mill established by a group of Pennsylva- nia Quakers. In the thriving agricultural Scioto Valley, a number of men became important import-export merchants, obtaining their goods via annual trips to New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, and packing and selling their pork by flatboat to New Orleans. These men helped make local newspapers possible, since they heavily ad- vertised the merits of their Eastern city goods. A number of mer- chants were immigrants, including Scotsman John McLandsburgh, and John Waddle and John Carlisle of Ulster, but James McCoy, William McDowell, James McClintick, John McDougal, Joseph

12. William Renick, Memoirs, Correspondence and Reminiscences of William Renick (Circleville, 1880), 4-79; Charles Samner Plumb, Felix Renick, Pioneer (Columbus, 1924), 8-11; Robert L. Jones, Ohio Agriculture During the Civil War (Columbus, 1962), 4-9; and Paul C. Henlein, Cattle Kingdom in the Ohio Valley, 1783-1860 (Lexington, Ky., 1959), 8-14, 103-16, 131. |

146 OHIO HISTORY

Brown, Thomas James, and other men also

operated flourishing

stores or pork-shipping businesses.

James, a Virginian, branched out

into other enterprises, and ended up

operating a large ironworks.

Carlisle and Waddell invested in a

brewery. William McDowell be-

came a doctor, while Isaac Cook of

Connecticut, originally a land

agent for Pittsburgh's John Neville,

manufactured nails.13

The leading men of the Scioto Valley

also exploited political office.

As historians have observed, the

Northwest Territory developed a

political patronage system binding

locally prominent men to the cen-

tral government. Governor Arthur St.

Clair's appointees, in turn, were

men who either had good Eastern

references or who had already

achieved some prominence in the

frontier, and their appointments

brought them both income and status.

Thomas Worthington sought

offices in the land office, while

Nathaniel Massie tried to use territori-

al politics to get his promotional towns

made county seats. This sys-

tem continued after statehood, when

Worthington's ties to the Jeffer-

son Administration made him the chief

distributor of Ohio

patronage. 14

Thanks to deft maneuvering by a

Territorial delegate to Congress,

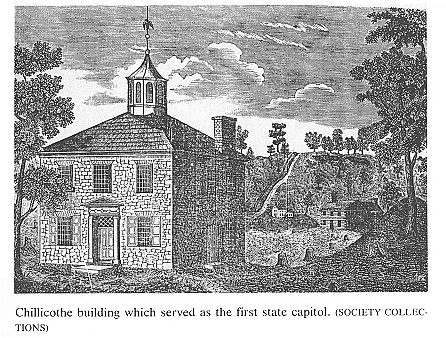

Chillicothe became the Northwest's

capital. Although Cincinnati

and Marietta politicians in the

Territorial Assembly passed a bill to

switch the capital to Cincinnati, Thomas

Worthington used his ties

with the Jefferson Administration to

lobby successfully for state-

hood. Chillicothe was denoted the site

for Ohio's constitutional con-

vention, and became the state's first

capital. The seat of government

shifted briefly in 1811 to Zanesville,

but returned to Chillicothe be-

fore it was finally established in

Columbus, further up the Scioto.15

13. Lyle Evans, Ross County 1:79,

171-72, 265, 490-91; Williams Brothers, History of

Ross and Highland Counties, Ohio (Cleveland, 1880), 210-14; Bennett, Ross County,

145-47, 224-25; Fortescue Cuming, Sketches

of a Tour to the Western Country . . . in 1809

(Pittsburgh, 1810, reprinted in Reuben

Gold Thwaites, ed., Western Travels, 1748-

1846, 32 Vols, 1904-1907, reprinted New York, 1966),

4:212-19; William R. Southward,

Chillicothe Reminiscences (Chillicothe; 1811 memoir, reprinted 1950); and

Chillicothe

Scioto Gazette, microfilm edition, Western Reserve Historical Society,

February 20,

April 16, and May 7, 1804.

14. Sears, Thomas Worthington, 36-42;

and Cayton, Frontier Republic, 82-83.

15. John Theodore Grupenhoff,

"Politics and the Rise of Political Parties in the

Northwest Territory and Early Ohio to

1812 with Emphasis on Cincinnati and Hamil-

ton County," Ph.D. thesis,

University of Texas at Austin, 1962, 70-77; Journal of the

House of Representatives of the

Territory of the United States, North-West of the Ohio,

at the First Session of the Second

General Assembly (Chillicothe, 1801),

71-73; Thomas

Worthington to Nathaniel Massie, March

5, 1802, Thomas Worthington Collection, mi-

crofilm edition, Ohio Historical

Society, roll 2, frames 265-69; and William T. Utter, The

Frontier State: 1803-1825, (Columbus, 1942), 53-54.

Chillicothe's Elite 147

As a governmental center, Chillicothe

naturally attracted an unusual

number of lawyers. These attorneys came

from many places. Michael

Baldwin, a Connecticut lawyer, curried

favor with Chillicothe's arti-

sans, and enjoyed additional power

because two of his brothers,

Henry and Abraham, were important

politicians in Pittsburgh and

Georgia. Other notable lawyers included

Henry Brush of New York,

Englishman Levin Belt, Virginian William

Creighton, William K.

Bond of Maryland, and Frederick Grimke,

a South Carolinian who

did not follow his famous sisters into the abolition movement.16

Chillicothe also became a newspaper and

legislative printing center,

with Bostonian Nathaniel Willis

operating the Jeffersonian Scioto Ga-

zette, and Massachusetts Yankees George Denny and George

Nashee

a rival Federalist paper, the

Chillicothe Supporter.17

The new community played a crucial role

in territorial and state pol-

itics, especially before the War of

1812. The Scioto counties, settled

earlier than other parts of Ohio, held a

large share of the state's pop-

ulation; thus, in the 1802

constitutional convention, Ross and Adams

Counties, the two Scioto Valley

jurisdictions, got nine of the thirty-

one seats.18 In addition, men

like Thomas Worthington and Michael

Baldwin enjoyed many ties with

Jeffersonian leaders in Washington.

Ohio's Republicans dominated state

politics, since Federalist vot-

ers represented at most one-fourth of

the electorate. Within the Re-

publican party, the most important

Republicans came from the

Cincinnati-Dayton region (which elected

one Senator and the sole

Congressman) and from the Scioto Valley.

Thus, Chillicothe's lead-

ers were among the state's most

important. Thomas Worthington and

his brother-in-law, Dr. Edward Tiffin,

dominated one wing of the

state party. The men in this group were

sober Methodist converts. A

rival faction centered on Michael

Baldwin and Elias Langham. Their

supporters included artisans and

farmers, some part of a group of

16. William T. McClintick, Sketch of

the Life and Character of William Creighton, Jr.,

Ross County Historical Society archives;

Cayton, Frontier Republic, 83-88; Gerda

Lerner, The Grimke Sisters From South

Carolina; Pioneers for Women's Rights and Ab-

olition (New York, 1967), 342-43; Lyle Evans, Ross County, 1:104;

Dumas Malone,

"Abraham Baldwin," Allen

Johnson, ed., Dictionary of American Biography (New

York, 1928), 1:529-32; and Lindsay

Rogers, "Henry Baldwin," Johnson, ed., Diction-

ary of American Biography, 1:533-34. Grimke opposed abolition, but freed his own

slaves.

17. Lyle Evans, Ross County, 1:356-59.

Denny and Nashee were vituperative; see for

examples the Chillicothe Supporter, microfilm

furnished by the Ohio Historical Socie-

ty, October 6 and 13, 1808, and April 6,

13, and 20, 1809. After Mrs. Denny died, her

husband sold his share of the paper, and

Nashee ran a more moderate publication.

See for example Supporter, March

12, 1816.

18. Daniel J. Ryan, ed., "From

Charter to Constitution," from Ohio Archaeological

and Historical Society Publications, Vol. V (Columbus, 1897), 80-132.

148 OHIO HISTORY

rather rough people called "The

Bloodhounds." These men joined

in riots, and prevented sheriffs from

arresting Baldwin for his debts.

Nathaniel Massie and his brother-in-law,

William Creighton, worked

with both groups. They backed the

Worthington wing in 1803-1807,

but later swung into independent

opposition. Massie became

Langham's drinking partner. Chillicothe

had some Federalist politi-

cians, including Levin Belt, a bluff,

hearty Englishman whose per-

sonal popularity crossed party lines and

allowed him to serve as may-

or. The county's Senate and House seats

revolved with fair regularity

among a number of the community's

leaders; during the period

1803-1819, fifteen men held the two

state Senate seats, while the

House seats were occupied by more than

forty men.19

The Chillicothe Republicans, fairly

secure in their position within

state politics, fought each other, but

also learned to cooperate for the

community's good. Thus, Edward Tiffin

and Elias Langham, as

Governor and Speaker, surmounted their

personal dislikes, and

made sure that many of the state's first

roads centered on their com-

munity.20

This favoritism quickly bred a strong

anti-Scioto reaction in other

parts of Ohio. Voters in the outlying

regions, whether ex-Federalists

or moderate Republicans, began to unite

behind Republican candi-

dates like Samuel Huntington of Cleveland,

or Return J. Meigs, Jr., of

Marietta. The Scioto Republicans

responded by creating secret polit-

ical clubs, the Tammany Societies, to

try to enforce political regulari-

ty. During the War of 1812, the various

Republican wings in Ohio

came back together, a development

symbolized by Worthington's

tenure as Governor in 1814-1818.21 After

Worthington retired from ac-

tive state politics, other Chillicothe

landowners and businessmen

moved to the political fore. Duncan

McArthur became Governor in

1830-1832, while lawyers Henry Brush and

William Creighton often

represented the Scioto Valley in

Congress. In the period after 1835,

19. Edward Tiffin to Thomas Worthington,

January 8, 1806, Worthington Collection,

letter on loan from the State Library of

Ohio, roll 4, frames 20-22; Cayton, Frontier Re-

public, 79-94; Bennett, Ross County, 124; and Judge John

H. Keith, They Cast a Spell:

Essays on the Bar (Chillicothe, 1943, reprint ed., originally

Chillicothe: The Ross

County Register, 1870), 9-10. Local state Senators during this period

included

Nathaniel and Henry Massie, Joseph Kerr,

William Creighton, Henry Brush, and

Duncan McArthur.

20. William Creighton, Jr., to Thomas

Worthington, March 5, 1804, Worthington

Collection, roll 3, frames 226-28, letter on loan from the State

Library of Ohio.

21. Jeffrey P. Brown, "The Ohio

Federalists, 1803-1815," Journal of the Early Re-

public, Vol. 2, Fall 1982, 261-82; Jeffrey P. Brown,

"Samuel Huntington," 420-38; and

Sears, Thomas Worthington, 184-209.

|

Chillicothe's Elite 149 |

|

|

|

orphan William Allen, a highly successful Chillicothe attorney and McArthur's son-in-law, became a Congressman and Governor.22 Intense rivalry in business and politics caused many casualties among Chillicothe's new elite. Some of the men who lost early politi- cal prominence responded by turning to alcohol. Elias Langham and Michael Baldwin became hopeless drunks, while Nathaniel Massie went through alcoholic binges.23 Samuel Finley, a territorial county judge, served for years as a director of both the Bank of Chillicothe, founded in 1808, and of the Chillicothe branch of the Bank of the United States. He also invested in a steam flour mill. Finley went bankrupt during the Panic of 1819, and his death left Thomas Wor- thington mired in co-signed notes. Worthington remained an energet- ic investor, and sent his son James to England and France to study in- dustrial techniques, but was also reduced during this period to

22. Bennett, Ross County, 118-19, 122. 23. Edward Tiffin to Thomas Worthington, January 19, February 17 and 20, and November 30, 1804, and January 8, 1806, Worthington Collection, roll 3, frames 136-83, 200-04, 205-07, 357-59, and roll 4, frames 20-22, letters on loan from the State Library of Ohio; and Tiffin to Worthington, December 14, 1804, Worthington Reel 90, Ohio His- torical Society. |

150 OHIO HISTORY

plowing his own fields.24 Joseph

Kerr, the merchant and meat pack-

er, served as a U.S. Senator, but when

the government delayed re-

paying him for money laid out for War of

1812 supplies, Kerr went to a

debtor's cell. He lost more money when

he had to forfeit land sold

him by Nathaniel Massie (the land went

to a prior purchaser with a

better title), and by 1824 Kerr was

bankrupt. Kerr hoped to re-

coup his fortunes by backing Andrew

Jackson for President, but

development-minded Chillicotheans

preferred Henry Clay, and Kerr

eventually left Ohio for Louisiana.25

Some new men entered the

town's elite. Thus, Virginian John

Madeira married Felix Renick's

daughter, and became a hotel operator

and turnpike investor. Abra-

ham Hegler, another Virginian, bought

5,000 acres in 1809, and be-

came an importer of English shorthorn

cattle. Other men, like mer-

chant Humphrey Fullerton or Judge John

Thompson, simply moved

on. Thompson became a Louisiana planter,

while Fullerton went to

Texas to become a land empresario and

died in a steamboat explo-

sion.26

While the members of Chillicothe's elite

often competed with

each other, they also learned to work

together for mutual benefit.

Thomas Worthington and Duncan McArthur

represented rival wings

of the Republican party, but located

land for each other. Worthing-

ton and Joseph Kerr were partners in a

Portsmouth, Ohio,

packinghouse run by Kerr's son-in-law,

Amaziah Davisson. Wor-

thington and Samuel Finley operated

rival flour mills, but were politi-

cal allies in the early 1800s and backed

each other's notes. A group of

merchants headed by Humphrey Fullerton,

John Carlisle, and John

McLandsburgh pooled their efforts in

1815 to erect a toll bridge over

the Scioto. They received state

permission, and their bridge, which

replaced earlier ferry boats, made the

town's economy function

much more efficiently.27

Chillicothe's elite also dominated their

town's cultural institutions.

Governor Edward Tiffin was the prime lay

preacher at Chillicothe's

Methodist church for years, until he was

expelled by the more con-

servative members during a political

quarrel. Since Tiffin was a mem-

24. Finley and Putnam, Pioneer

Record, 131; Sears, Thomas Worthington, 214, 231,

235-36; Cayton, Frontier Republic, 128;

and Minutes of the Board of Directors of the

Bank of the United States at

Chillicothe, 1817-1825, Ross County

Historical Society ar-

chives.

25. Dickore, ed., General Kerr, 33-102.

Two of Kerr's sons, early Texas settlers, died

at the Alamo.

26. Lyle Evans, Ross County, 1:176-77,

266-67, 649; Bennett, Ross County, 200.

27. Sears, Thomas Worthington, 17,

214, 231; Dickore, General Kerr, 42; and Ben-

nett, Ross County, 70.

Chillicothe's Elite

151

ber of the liberal Republican Tammany

society, the conservatives

charged that he was really worshipping

an Indian saint!28 St. Paul's

Episcopal Church, created in 1817, was

soon Chillicothe's most pres-

tigious church. Mayor Levin Belt and

iron-maker Thomas James

served as its wardens, while lawyers

Henry Brush, William K. Bond,

and Richard Douglas, and merchant

William Southward played im-

portant roles in its affairs. So did

Edward King, the son of powerful

Federalist Senator Rufus King of New

York. When he married one of

Thomas Worthington's daughters, Edward

King instantly became

one of Chillicothe's leading

Episcopalians.29 The merchants who lat-

er built the toll bridge-Carlisle,

McLandsburgh, and Fuller-

ton-dominated Chillicothe's Presbyterian

church. Carlisle fi-

nanced the construction of a building in

1809, while Fullerton and

McLandsburgh became church trustees.

Thomas Worthington's

wife Eleanor donated property for a

parsonage.30 Edward Tiffin and

Worthington's relative T. V. Swearingen

dominated Chillicothe's Af-

rican Colonization Society, while James

Dunlap founded a county

poorhouse and farm.31

During its early years, Chillicothe

relied on a private log cabin

schoolhouse, but in 1809 the community's

leaders organized the

Chillicothe Academy. It was a somewhat

haphazard Lancastrian

school, but in 1815 the Academy was

reorganized and put under the

leadership of the Reverend James

McFarland of the Presbyterian

Reformed Church. The trustees of the

Academy included then-

Governor Thomas Worthington, War of 1812

General Duncan McAr-

thur, Thomas James, John Carlisle, and

banker Samuel Finley.

Worthington and cattleman George Renick

dominated the board in

later years. They financed the

construction of a fine two-story school

with a cupola.32

28. R. Carlyle Buley, The Old

Northwest; Pioneer Period, 1815-1840, 2 Vols. (Bloom-

ington, 1950), 2:448; and William Utter,

"Ohio Politics and Politicians, 1802-1815,"

Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago,

1929, 111-16.

29. Bennett, Ross County, 219;

Lyle Evans, Ross County, 1:164; and L.W. Renick,

Che-Le-Co-the; Glimpses of Yesterday (New York, Press, 1896), 171-73. Although

Thomas Worthington was a leading

Methodist, his wife became a Presbyterian, and

several children joined the Episcopal

Church.

30. Lyle Evans, Ross County, 1:249;

and L.W. Renick, Che-Le-Co-the, 54, 92, 150-53.

The Presbyterians dispensed with all

musical instrumentation, and their church

strongly condemned slavery. It admitted

two black families, the James Hills and Billy

Dailys, as members.

31. Bennett, Ross County, 63; and

Colonization Society, Ross County Historical Soci-

ety archives.

32. Bennett, Ross County, 54;

L.W. Renick, Che-Le-Co-the, 142; and Chillicothe

Academy Record Book, Ross County Historical Society Archives.

152 OHIO HISTORY

In 1820, an Englishman named Steinour

opened the Young Ladies'

Boarding School. Within two years, this

institution was replaced by

the Female Seminary, founded by Yankees

Cassandra Sawyer and

Eunice Strong. The attendees at this

school included a number of

young Worthingtons, Creightons, and

Tiffins. Thus, both the sons

and daughters of the elites had an

opportunity to go to school, and

began to form closed circles.33 Accounts

left by the young women

make it appear that their lives revolved

around an endless series of

social gatherings.34

The members of Chillicothe's elite

cooperated with other fashions

beyond business, politics, faith, and

schools. During the War of

1812, John McLandsburgh and William

Southward headed up a

committee that urged defense

preparations in case of attack. When a

serious fire in 1820 caused considerable

damage, Mayor Belt created

a fire company. Belt appointed Thomas

James the director, Edward

King one of his assistants, Joseph Kerr

the captain of the bucketmen,

and a number of successful

merchants-John McCoy, James Miller,

John McLandsburgh, and others-as other

officers.35 Many of

Chillicothe's leaders joined each other

as members of Scioto Lodge

No. 2 of the Free and Accepted Masons.

The Lodge included such

members as Elias Langham, Henry Massie,

Levin Belt, Henry Brush,

Nathaniel Willis, William Creighton, and

immigrant printer John

Bailhache. While these men represented

every part of the political

spectrum, they became brothers as

Masons.36

Chillicothe's leaders recognized that

their town's prosperity de-

pended upon agriculture. Many of them

were important landowners

as well as merchants, and rented lands

or hired laborers for their

holdings. They took a strong interest in

agricultural improvements,

and especially in improving the

bloodlines of their cattle. In 1819, the

Renick clan began a drive to start a

Scioto Agricultural Society Cattle

Show. These shows, and the annual

general county fairs begun in

1833, probably increased the interest

that Ross Countians began to

take in cattle genealogy. By 1833, Felix

Renick, John Dunn, and Dun-

can McArthur took the lead in creating

the Ohio Company for

Importing English Cattle, and several Renicks

soon went to England

33. L.W. Renick, Che-Le-Co-the, 106-107;

Works Progress Administration, Chillico-

the, n.d., 39. Tiffin's first wife, one of Thomas

Worthington's sisters, died young. Tif-

fin remarried, and his daughters came

from his second marriage.

34. Renick, Che-Le-Co-the, 98-99;

Sears, Thomas Worthington, 113.

35. Finley and Putnam, Pioneer

Record, 129; and on the defense committee, Ross

County Historical Society archives,

Folio 24.

36. Lyle Evans, Ross County, 1:339-42.

Chillicothe's Elite 153

to buy blooded bulls. The Scioto Valley

soon became an important

region for cattle breeding, and the Ohio

Company and its successor,

the Scioto Valley Importing Company,

flourished well into the

1850s.37

Chillicothe became, during the 1820s and

1830s, the most impor-

tant Midwest center for cattle feeding

lots. Once again, the Renick

clan led the movement into this new

enterprise. Renicks and other

cattle barons began to make annual trips

to new frontier states like Illi-

nois and Missouri, buying scrubby

cattle. They drove them to Ross

County, fed them Scioto Valley corn

until they grew fat, then herded

them to the East Coast. Hog drives to

Baltimore and Richmond sup-

plemented the cattle trade. By 1832, the

Renicks were importing

12,000 cattle a year, with the herds as

collateral for Bank of Chillico-

the 10 percent loans. The whole Valley

handled 45,000 or more cattle

a year, and 25,000 stock hogs.38

As this cattle and hog feeding empire

grew, Ross County farmers

grew less wheat and more corn. The area

had long exported its own

animal surplus. In 1817, 200 cattle were

herded to New York, while

Huffnagle and McCollister, a firm

specializing in barreled beef,

opened butchering operations in

Chillicothe in 1819. They flat-

boated their beef down the Scioto. Most

entrepreneurs continued

their overland drives, which grew larger

and more important as the

flow of Midwestern cattle increased. In

1842, William Renick led the

first drive to Boston, the nation's

tanning center.

Cattle feed lots became more important

in the later 1840s when rail-

roads entered Ohio, since cattle could

be shipped East from Ohio

with minimal weight loss. Of course,

this eliminated most overland

drives. Chillicothe developed large

slaughterhouses in the 1840s, as

firms like Fraser's, or Campbell and

Brown and Company, imported

Irish workingmen familiar with preparing

meats for the English mar-

ket. The first railroad to enter

Chillicothe, the Marietta & Cincinnati

(Felix Renick, President), was finished

in 1852.

Rapid expansion of the railroad network

soon ended the Scioto

Valley's cattle primacy. By 1854,

cattlemen in Illinois and Missouri

could ship directly to market, and this

reduced the need for Ohio

37. Buley, Old Northwest, 1:192-99;

Henlein, Cattle Kingdom, 76-97; and Plumb,

Felix Renick, 30. Various Renicks owned nineteen of the ninety-two

shares in the Ohio

Company for Importing English Cattle,

while Duncan McArthur held six shares. John

Dunn soon broke with his partners, and

began a rival bull importation program.

38. Buley, Old Northwest, 1:528-29;

Henlein, Cattle Kingdom, 6-11; William Renick,

Renick, 8-14, 47-48; Clark, Grain Trade, 132-33; and

Margaret Walsh, The Rise of the

Midwestern Meat Packing Industry (Lexington, Ky., 1982), 22, 92.

154 OHIO HISTORY

feeder lots and Chillicothe packing

houses. Scioto Valley farmers

continued to raise corn, but it now went

directly into whiskey pro-

duction. They also raised fewer cattle

and hogs, and more sheep for

the wool trade.39

Transportation changes like the railroad

extensions clearly affected

Chillicothe's growth. Early state roads

centered on Chillicothe,

making it the center of Southern Ohio

overland commerce. Chillico-

the's roads linked the town to

Cincinnati, Portsmouth, Marietta,

Wheeling, and Columbus. The community

also served as a major fo-

cal point for downriver Scioto commerce.

In 1831, the assembly au-

thorized a turnpike between Portsmouth

and Columbus, with

Chillicothe in the middle. William

Renick was the road's prime pro-

moter, while James Worthington and David

Renick took charge of

construction with in Ross County. Ohio

financed two state canals,

one running from Portsmouth to

Cleveland. The canal's Chillicothe

leg, completed in October, 1831, sharply

cut transportation costs to

the Great Lakes. Chillicothe eventually

became the logical division

point along the canal. To the south of

Chillicothe, farm goods flowed

towards Portsmouth and the Mississippi

Valley. Farm products from

above Chillicothe went to Cleveland and

the East Coast. This gave

Scioto Valley farmers a good deal of

access to both markets. The

construction of railroads into Ohio in

the 1840s and 1850s simply

completed Chillicothe's links to the

nation's economy.40

Banking further wove Chillicothe into

the nation's economy. The

state chartered a local bank in 1809,

with the Bank of Chillicothe

using the Masonic Hall as its

headquarters. Samuel Finley, Thomas

James, and John Woodbridge dominated

this bank. A branch of

the Second Bank of the United States was

established in Chillicothe

in 1817, with a board that included most

of Chillicothe's elite-

President William Creighton, Edward

Tiffin, Duncan McArthur,

Samuel Finley, John McLandsburgh, George

Renick, John McCoy,

William K. Bond, Edward King, John

Carlisle, and William

McFarland, among others. Ties to the

national economy meant pros-

perity, but they also made Chillicothe

vulnerable to downswings in

the larger marketplace. By 1818, as

notes from many banks flooded

the Northwest, Chillicothe banknotes

circulated at a 15-20 percent

discount. Sharp credit constrictions

during the Panic of 1819 took

39. Henlein, Cattle Kingdon, 132,

143, 172-73; and Jones, Ohio Agriculture, 6-9.

40. Buley, Old Northwest, 1:432-33,

447, 466, 536; Lyle Evans, Ross County, 1:85;

William Renick, Renick, 83; and Williams

Brothers, Ross and Highland Counties,

152-53.

Chillicothe's Elite 155

leading Chillicotheans like Samuel

Finley or Joseph Kerr into bank-

ruptcy, while the B.U.S. proved so

unpopular that Ohio authorized

mercenary John Harper to invade the bank

and carry off $120,000 in

state taxes. Nevertheless, the B.U.S.

branch functioned in

Chillicothe through 1825, and the town

acquired other chartered

banks.41

Chillicothe's elite controlled most

aspects of community life. This

should not infer that ordinary citizens

were powerless. During the

early statehood period, they elected

popular leaders like Elias Lang-

ham and Michael Baldwin, while

conservative leaders like Thomas

Worthington worried about the

intimidating powers of the "Blood-

hound" artisans. When Worthington

and Edward Tiffin first created

a secret political club, the Tammany

Society, to enforce regular chan-

nels of authority within the Republican

Party, Tiffin wound up getting

expelled from his church. However, by

the time that Chillicothe

was fifteen years old, it had settled

into confirmed social patterns.

The earlier instability passed and some

twenty or so men controlled

most of the community's civic and

economic affairs.42

Unlike most early Ohio communities,

Chillicothe had a fairly large

black population. Ross County had about

one hundred free black

men, many with families. Most of these

men were tenant farmers or

mill hands who worked for former owners

like Thomas Worthington.

These laborers had no power at all, and

simply worked at hard

trades. However, some of Chillicothe's

blacks enjoyed some promi-

nence and had roles within their own

community. Jim Richards, the

town barber, also served as

Chillicothe's drum major. One member

of the black community, Morris O'Free,

prospered as the town's

chief caterer. O'Free hosted many of

white Chillicothe's civic func-

tions, including the many Female

Seminary affairs. Black people were

allowed to worship in several of

Chillicothe's churches. When white

Methodists insisted that black

worshippers take communion last, the

blacks seceded from the church, and in

1821 formed Quinn Chapel

of the African Methodist Episcopalian

Church. Although black

Chillicotheans could not challenge the

overall patterns of community

life, they had, like white artisans, at

least some influence on their

destinies.43

41. Sears, Thomas Worthington, 201-11,

231; Finley and Putnam, Pioneer Record,

131; Lyle Evans, Ross County, 1:373;

Buley, Old Northwest, 1:129, 572; Cayton, Frontier

Republic, 120-32;

and Minutes of the Board of Directors of the Bank of the United States

at Chillicothe, 1817-1825, Ross County Historical Society archives, November 10,

1817,

and September 17, 1819.

42. Cayton, Frontier Republic, 83-94.

43. L.W. Renick, Che-Le-Co-the, 99,

235; Lyle Evans, Ross County, 1:334; and Cay-

ton, Frontier Republic, 57-58.

156 OHIO HISTORY

Chillicothe's dominant elite brought

their community prominence,

power, and some wealth. At the same

time, their control probably

hurt the town's long-term growth. Many

of the wealthy landowners

who lived in Chillicothe preferred to

rent out their Scioto Valley

lands rather than sell them. While most

in the end found it necessary

to sell lands, their preference for

renting deterred many pioneer farm-

ers from taking up residence in the

Scioto, and led others to move on

to cheap and good soil elsewhere. Thus

the Scioto Valley grew rath-

er slowly after 1810, and became less

important politically. As other

areas of Ohio opened up, these outlying

regions resented Chillico-

the's early political power and arrogant

allocation of roads. The state

capital was shifted to Zanesville, and

by 1817 moved permanently to

Columbus, at the upper end of the Scioto

Valley. The National Road,

the most important pre-railroad artery

of commerce, subsequently

passed through Columbus, not

Chillicothe. By the 1830s,

Chillicothe was no longer one of Ohio's

dominant communities. But

the town remained prosperous. It

weathered a cholera epidemic, and

during the 1840s it began to attract

some of the German immigrants

who were settling in Ohio in large

numbers. Chillicothe eventually

became 40 percent German, and the new

settlers helped create a peri-

od of general prosperity. The town

remained a pleasant, modest-

sized community, with a well established

local elite controlling most

civic and economic affairs.44

Chillicothe offers a fascinating example

of the process through

which a new community developed a

controlling elite. Some of its

leaders were self-made frontier

surveyors, or immigrant merchants.

However, a large share of the town's

leaders were prominent men in

their home states. Some were wealthy

investors, or well-connected

surveyors. Others had a legal

background, or enjoyed family ties to

important national political figures.

Chillicothe's new leaders com-

peted vigorously in business and

politics, with some slipping into pov-

erty or alcoholism or both. Several

prominent men moved on to other

regions. Those who stayed and succeeded

in Chillicothe built en-

during estates. They invested in a wide

variety of businesses, includ-

ing land, cattle feeding, banking,

transportation, and milling. They

served together on civic boards, in

political offices, in fraternal socie-

ties, and as church leaders. Their

children attended the same

academies. Within a single generation,

Chillicothe produced a recog-

nizable elite of civic

leaders-prosperous, powerful, and active men

who dominated life in their new

community.

44. Bennett, Ross County, 77.