Ohio History Journal

BRADDOCK'S DEFEAT

by JOHN SCHLEBECKER

Hiram College

One of the things with which the reader

of early American

history is most impressed is the

remarkable courage and wisdom

of the American soldier. The Europeans

it seems just did not

understand the ins and outs of forest

fighting. Only the American

seemed to know that effective fighting

on the frontier was by neces-

sity done from behind trees. History

books are full of pictures of

minute men shooting redcoats, but they

do not have many pictures

of minute men running away from

redcoats. History books do say

that Von Steuben came to America to

teach Patriot soldiers how

to fight like Europeans, but they do

not point out clearly enough

that fighting behind trees was in those

days a rather silly way to

fight. And this last fact, of course,

explains the first. Part of the

purpose of this paper is to show how

and why fighting from behind

trees was in the early days a poor way

to fight.

From this misconception of forest

fighting has come some

peculiar reports of forest battles, the

most peculiarly reported of

all being Braddock's defeat at the

Monongahela. In this paper the

story of that battle will be retold and

some sort of evaluation of it

will be made. The evaluation will not

be the customary one.

In order that the evaluation of the

battle have validity, there

will be a brief review of the arms,

soldiers, and tactics of the period.

The period to be considered is the last

half of the eighteenth cen-

tury; the date of the battle was July

9, 1755.

The chief weapon of the armies of this

time was the musket.

This weapon was inaccurate at any range

over one hundred yards

and even at that distance or less it

was so inaccurate that individual

firing was relatively harmless.1

Of the other weapons of the period only

two require mention

here. One was the familiar three-sided

bayonet, and the other was

the light field cannon used to fire

upon infantry formations in the

field.

1 Edward M. Earle, Makers of Modern Strategy (Princeton, 1943), 51.

171

172

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

The typical soldier of this period was

the professional who en-

listed for long terms and who fought as

a business.2 He was

chiefly interested in his pay; he fought

without political passion.

If his food supply was reduced or if

operations should prove to

be unduly strenuous his morale would

drop.3 Under these circum-

stances he would be inclined to desert.

So prevalent was desertion

that men were required to march in close

order when going and

returning from bathing. They could not

be trusted to forage for

food, to pursue an enemy, or even to

take cover in a fight because

in these activities they were liable to

get out of their officer's sight

and desert. Even camping near forests

was dangerous because of

the temptation it offered to deserters.4

The Indian also was a mercenary soldier,

with this difference:

his pay was chiefly in loot and so he

was inclined to stick around

the battlefield a little longer to see

what he could pick up.

Tribal warriors fought under their own

chiefs and generally

near their homes. If a clan or tribe

should be bored or should

think that the fight was not to their

advantage they would take a

rest. They were liable to do this any

time the idea occurred to

them.

Tribal warfare is different from

civilized warfare in that all

men of a tribe are related, and

therefore a casualty is a deep per-

sonal tragedy to all the men of that

tribe.5 Thus any considerable

number of casualties in a tribe may

cause that tribe to withdraw

sooner than a civilized platoon or

battalion would withdraw.

The range and accuracy of the musket

determined the tactics

used by Europeans. Since the musket was

inaccurate and had a

short range the men advanced into battle

shoulder to shoulder and

fire began at only a little over one

hundred yards. Each battalion

fired as a unit at the word of command.

The battalion was usually

three ranks deep and the fire from it

was terrible and deadly.6 The

ultimate object of the fight was to

close with the enemy on a

bayonet charge.7

2 Ibid., 50.

3 Ibid., 51.

4 Ibid., 55-57.

5 T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom (Garden

City, 1938), 194.

6 Earle, op. cit., 51.

7 William Wood and Ralph H. Gabriel, The

Winning of Freedom (The Pageant

of America, VI, New Haven, 1927), 197.

BRADDOCK'S DEFEAT 173

It took time to draw the armies up into

battle line, and thus

if one side decided to leave while the

other was forming there

could be no real battle.8

The technique of destructive pursuit was

undeveloped at this

time.9

Firing was done by alternating platoons

or battalions. This

was done because the difficulty of

reloading and the nearness of the

troops made bayonet charges particularly

dangerous.10

When troops were marching through woods

the tactics of the

day required that they march in platoon

formation so that they

could be more easily maneuvered in case

of action. In case the

vanguard did meet the enemy the main

force was to be halted until

the commanding officer knew what was

happening. This because

once the troops were formed it was

difficult if not impossible to

rearrange the formation. In addition, a

commanding officer should

know something of the size and

disposition of the forces opposing

him before going into action.11

The tactics of the Indians and colonials

was a hit and run kind

of warfare. The Indians probably used it

because in tribal warfare

(aside from blood feuds) the object is

to sustain minor losses, kill

as much as necessary, and steal

everything that can be stolen.

Where loot rather than murder is the

primary object the tactics are

liable to be so constructed that

efficiency in killing is sacrificed for

safety in getting home with the bacon.

The colonials probably

used this type of warfare because they

were not numerous enough

to put massive armies in the field.12 Most historians hold that

massive armies would not have been

effective anyway. This argu-

ment causes one to wonder why the

colonials were always trying

to raise armies to fight the Indians if

armies were not the answer.

The first thing that Braddock tried to

do upon arrival in

America was to turn the colonial troops

into real soldiers. He had

them drilled in the European manner by

British officers and en-

forced an old regulation that colonial

officers were to have no rank

8 Earle, op. cit., 51.

9 Ibid., 52.

10 Wood and Gabriel, op. cit.,

196.

11 Stanley Pargellis, "Braddock's Defeat," American

Historical Review, XLI

(1936), 264.

12 Wood and Gabriel, op. cit., 17.

174

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

while regular officers were in the

field.13 These actions only made

the colonials bitter and caused a drop

in morale.

Soon after setting out the troops were

subjected to an epidemic

of fever and dysentery. This naturally

caused a considerable lower-

ing of morale which a lack of sufficient

food only made worse.

The line of march was over rough terrain

which added to the

woes of the British soldiers. These

became disheartened at their

hardships, while the colonials continued

to be soured by army dis-

cipline. The whole army was in a poor

psychological condition.

Engineers preceded the troops, clearing

a roadway twelve feet

wide while squads of men were sent out

in front and on all flanks

to guard against surprise. These squads, however, were not

numerous enough to offer effective

security. The entire length of

the line of march was about four miles.

In order to avoid dangerous defiles on

the route, Braddock

decided to ford Turtle Creek and then

ford the Monongahela a few

miles down. It was on the other side of

this last ford that 1,300

British regulars and colonials met the

French and Indians.

Contrecoeur, the commander of the French

at Fort Duquesne,

was in favor of retreat. However, one of

his captains, Beaujeu,

felt that if he could get the Indians to

come with him he might stop

the English. Three times he tried to

talk the Indians into accom-

panying him, and on the third try he was

successful. His total

force included 230 French and Canadians

(70 of whom were

French regulars), and 637 Indians, a

total of 867 men.14 Of this

force three men were French officers:

Beaujeu, Dumas, and

Ligneris.

The French plan of battle called for an

ambush at the ford

which Braddock was to cross, but at the

crucial moment the Indians

decided to leave. Beaujeu managed to

talk them into continuing

the expedition and had barely managed to

reassemble his men

when he met the advancing British.

Despite this recent disaffection

the morale of the French and Indians was

considerably higher

than that of the British.

Beaujeu, dressed as an Indian, came

walking jauntily over the

13 William M. Sloane, The French War and the Revolution

(New York, 1898),

42.

14.Ibid., 44.

|

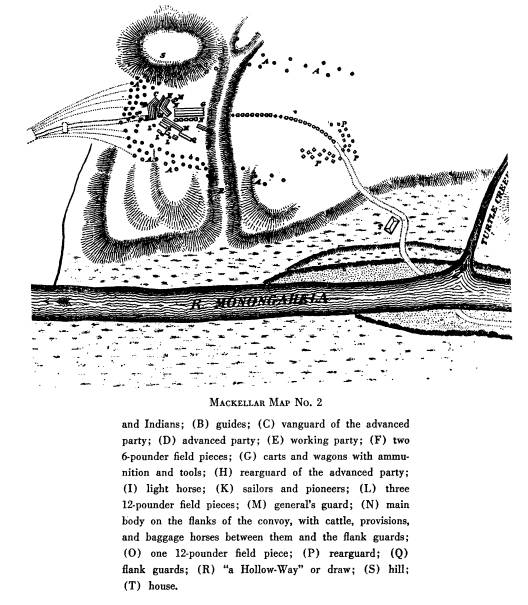

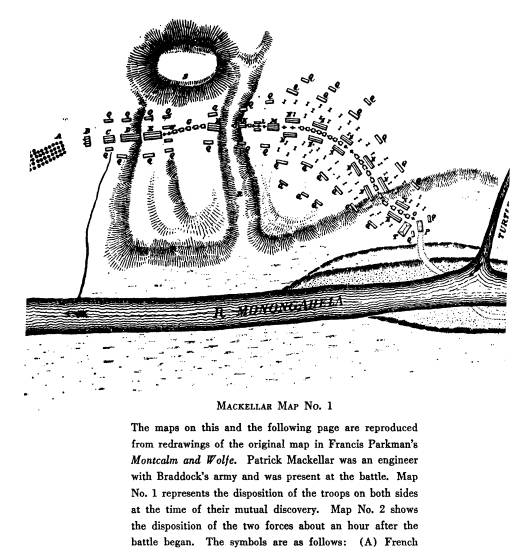

BRADDOCK'S DEFEAT 175 |

|

|

|

176 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY |

|

|

BRADDOCK'S DEFEAT 177

brow of a hill. On the other side a

British engineering officer was

mapping the route. Both men were

somewhat startled.

Beaujeu turned and with his hat signaled

his forces which de-

ployed and opened fire. With the

admirable precision and cool

courage of European soldiery the British

advance column under

Gage wheeled into line and fired several

volleys in the general

direction of the enemy. The British

casualties up to this point were

insignificant. Gage's cannon opened fire

quickly and the Canadians

and Indians fell back in confusion while

the British infantry con-

tinued to fire. Beaujeu fell dead.

It was at this point that seventy French

regulars, fighting in

European style, won the battle. With the

courage born of despair

Dumas advanced with the French regulars

and returned a fire which

was sharp enough to halt and surprise

the British.15 It seems

probable that after all of the talk that

they had heard about Indian

ambushes that the last thing the British

had expected to meet was

effective European fighting. They stood

it for about fifteen minutes

and then broke and ran.16 Meanwhile

the Indians and Canadians,

taking heart at the stand of Dumas and

the regulars, were gradually

reassembling behind cover and opening

fire upon the British.17

As the vanguard of the British broke and

fled it ran into the

main body of troops under Braddock which

were advancing to the

front. At this time Braddock had no

clear idea of what was happen-

ing and the troops were in a state of

confusion because the officers,

including Braddock, were not exercising

proper control.18 The sud-

den influx of the advance guard only

increased the confusion. Com-

plicating this confusion was the fact

that the main body was

split in two sections on either side of

the wagon train. This reduced

the mobility of the troops and made it

more difficult for them to

form for action.19 In any

case, the troops under Braddock were

still in column of march rather than in

battle formation because

"the order to form line of battle

had either not been given or had

not been heard."20 This

last fact is particularly important. It means

that the main body of the British at the

time of the encounter was

15 Francis Parkman, Montcalm and

Wolfe (2 vols., Boston, 1899), I, 223.

16 Wood and Gabriel, op. cit.,

76.

17 Parkman, op. cit.,

224.

18 Pargellis, loc. cit., 260.

19 Ibid., 269.

20 Wood and Gabriel, op. cit.,

76.

178

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

unprepared to fight in any manner be it

European or American. Too

late they attempted to perform this

complicated maneuver on rough

terrain, but being in disorder

themselves and at the same time meet-

ing the advance guard they never

completed the formation. The con-

sequent panic resulted as much from the

muddling confusion as

from the enemy fire.21

Dumas, noting the position of the

British troops, seized the op-

portunity to send out flanking parties along

both sides of the

enemy column. Had the British been in

line of battle this maneuver

would probably have been impossible due

to the extension of the

flanks and the fire power of the

British. In any case, it would

not have been as effective, because the

British could have launched

bayonet charges from the line of battle.

As it was the British were

nearly defeated already.

Meanwhile the Virginians had dispersed

behind trees and were

wasting their powder on marksmen as

unseen as themselves.22 The

Virginians did not suffer many

casualties, neither did they inflict

many. The total French and Indian losses

were only forty officers

and men.

At this point of the battle the worst

fire was coming from a

hill on the right. This hill should have

been taken as soon as the

action began, or even before, but the

command to take it was

not given until after the army was

helplessly piled up.23 At that

time Braddock ordered Lt. Col. Burton to

take the hill. The colonel

managed to get about one hundred men to

follow him, but upon

being wounded himself his men retreated.

Failure to take the hill

sooner shows Braddock's incompetency;

failure to take the hill at

all shows the complete dependence of the

soldier of the day on his

officers.

For three hours the French and Indians

poured in fire while

the British held. They "formed in

oblique angle lines, twelve or

more deep, while those in the rear

remained in column formation."24

They were never able to form an

effective line of battle. At the

same time the Virginians counseled the

British to take cover, an

action which Braddock refused to permit.

The British made excellent

21

Pargellis, loc. cit., 263.

22 Justin Winsor, The Mississippi

Basin (Boston, 1895), 362.

23 Pargellis, loc. cit., 265.

24 Ibid., 261.

BRADDOCK'S DEFEAT 179

targets, and at the same time they had

long since ceased firing by

battalions. Their fire power was gone.

After three hours Braddock

ordered a retreat, and soon thereafter

he was mortally wounded. The

retreat turned into a rout, but the

French and Indians did not

pursue. The battle was over.

The British opportunity for victory came

with the advance

of the main body. With the terrific fire

power of the battalions

(and the fire was tremendously effective

and deadly),25 plus the

possible bayonet charges, the enemy

could hardly have held their

ground. Through stupidity or bad luck,

however, the British arrived

in column, and that was that.

Parkman holds that a bayonet charge

would have been futile

against such a lurking enemy who would

dodge from one tree to

another, but his reasoning hardly holds

up.26 Later during the Revo-

lutionary War the British found that the

only way to drive men

from cover was to charge them. The

Americans, on the other hand,

when charged upon soon discovered that

the only way to keep from

being killed in the rush was to stand

like Europeans and fire by

battalions.27 They had to

correct some of the foolish notions that

they had picked up from fighting

Indians, who after all did not

use bayonet charges.

It seems probable that Braddock's

greatest failure was not in

what he wanted to do but rather in what

he did not do. If he had

formed his troops properly he might have

done some effective

damage. His failure to form his troops

might be attributed to the

fact that the murderous fire of an

unseen enemy threw his troops

into confusion and prevented any useful

action. This is undoubtedly

part of the answer, but it is entirely

too pat an answer to be the

complete explanation. Added to the fire

of the enemy was the fact

that the British officers " 'messed

up' their formations and never

gave their soldiers a chance to

demonstrate that Old World methods,

properly applied, might have won the

day."28

Another error of Braddock was this: he

did not observe the rules

of tactics of his own day in the matter

of marching through forests.

Bland, the leading tactical writer of

the period, stated that when

25 Earle, op. cit., 51.

26 Parkman, op. cit., 225.

27 Wood and Gabriel, op. cit., 197.

28 Pargellis, loc. cit., 253.

180

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

marching through woods the army should

be divided into platoons

for easier maneuvering. Whatever

formation Braddock's troops

might have been in, it was not a

formation by platoons.29

When the action first started Braddock

should have halted the

main body until he knew what was going

on at the front. Instead

he went blindly forward.30

In conclusion it should be said that the

error of Braddock was

not that he did not use American tactics,

but rather that he did not

even use good European tactics.

In regard to this battle many historians

make several explicit

or implied contentions which deserve

some notice since they recur

in almost all accounts. Briefly stated

they are five in number and

include the following ideas or notions:

1. The red-coated British in a

huddled mass made excellent

targets. This is certainly true. They were like so many pool

balls

racked up in the middle of the table. A

shot in the general direction

of the mass was sure to hit something.

It is remarkable that in

consideration of this fact some have

attributed a great deal of

marksmanship to the French and Indians.

They may have been

marksmen, but this action is hardly

proof of it. The great losses

in British officers can be attributed

not to sniper activity but rather

to the fact that in those days officers

were accustomed to stand in

front of their troops in order to direct

their movements and fire.

Under these circumstances the officers

were most likely to be killed

by one side or the other.

2. The British volleys were generally

wasted. Actually, the

first volleys of the vanguard were not

wasted. In fact they dispersed

and terrorized the Indians and

Canadians. After the retreat of the

vanguard the British can hardly have

been said to have fired volleys

with any consistency. If the troops had

been properly formed and

had fired by platoons it is not at all

certain that the volleys

would have been wasted.

3. The British should have taken cover

and fired independ-

ently. Usually this is followed by an implied corollary which

is:

Had the British taken cover they

would surely have won the battle.

This brings up the subject of relative

and absolute standards. If a

29 Ibid., 264.

30 Ibid.

BRADDOCK'S DEFEAT 181

man should bet ten dollars on a losing

horse it might be said that

he would have been better off to have

bet only five dollars. This

is obviously true. Relatively speaking,

however, it would have been

better still if he had bet on the

winning horse. It is hard to say what

the absolute good in this case might be,

but it would probably be

best not to bet anything.

Now a battle is a gamble, so it is

useless to discuss whether or

not it is right to take a chance in war,

because one cannot help but

take a chance. However, there are

intelligent bets and unintelligent

bets, and Braddock made some

unintelligent bets. Relatively speak-

ing, it would have been much better if

he had followed the advice

of the colonials and allowed his men to

deploy. This does not

mean that he would have won the battle

thereby, but only that his

losses in life might have been smaller.

His army would probably

have disappeared in any case. There are

several reasons for this.

In the first place the British soldiers

were fighting for a living,

and after the first few minutes even the

most stupid soldier could

have seen that there were easier ways of

making money. Had Brad-

dock allowed his men to disperse they

would have done just that.

Some may claim that this is mere

speculation, but the history of the

times shows that it is well founded

speculation. From Frederick the

Great to Washington the armies of the

world were cursed with the

tendency of troops to leave the field

when things got rough. The

extreme penalties which Frederick placed

on desertion, and the

difficulties which he encountered toward

the end of his reign in

keeping an army together are examples in

point.31 Another ex-

ample might be the difficulties that the

Americans experienced in the

Revolutionary War in keeping an army in

the field. One of the

reasons for close order fighting of this

period was that in close

order the men could be watched and if

any one tried to desert he was

shot or run through on the spot. It

would have been foolish to expect

the army of Braddock to act any

differently from any other army of

31 Earle, op. cit., 55-57.

182

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

the time.32 Only the

Americans seemed to be too dense to realize

this.

In the second place, if the British had

deployed, the French and

Indians would have had no targets and

the same might be said for

the British. The net result would have

been another backwoods

skirmish with both sides retiring for a

while, and then an ultimate

attack by the British on Fort Duquesne.

All of this presupposes that

the British army would hold together, an

unlikely occurrence. In any

case, the British by frontier methods of

fighting could not hope for

a positive decision until they could

manage to force the enemy into

a battle in the open. The British

soldiers were not trained for fron-

tier fighting, neither were they armed

for it. It took many years of

training to make a good frontier

fighter, and even then the arms of

the period did not allow it to be very

effective fighting. A conclusive

decision could only have been reached by

the use of European

tactics.33

Another reason why Braddock was right in

not following

Virginian instructions was that he had a

superiority in numbers and

in discipline which he would be less

than wise not to use. As long as

he had any chance at all to use this

superiority he would be foolish

to dissipate it by dispersing his men.

From the foregoing statements it is

possible to see that although

deployment would have been better than

what was done, at least

in respect to loss of life, it was not a

good solution.

What then would have been a good

solution? Proper use of

European tactics, which tactics

culminated in the bayonet charge.

There was nothing in America which would

make the bayonet charge

ineffective. In fact, as has been

pointed out, it was the only way of

dislodging men who were hiding behind

trees. And as Revolutionary

experience showed, it was not only

effective in that respect, but it

usually meant defeat for the deployed

forces since at the beginning

of the charge most of the defenders

would be inclined to fire. This

32 There are several reasons why these

same factors did not affect the Virginians,

Canadians, or Indians in the same manner

that they would have affected the British:

(1) these soldiers were not mercenaries

in the same sense as were the British;

(2) in their cases a certain amount of patriotism was involved; (3) they

were used to

this type of fighting; fighting where

every man was a general; (4) they were not

suffering many casualties; (5) on the French side at

least they were winning. On

the other hand, the Indians and

Canadians did start to leave at the beginning of the

fight and there is no sure way of

determining how many if any of these fighters

(including the Virginians) did desert

during the battle.

33 Pargellis, loc. cit., 265.

BRADDOCK'S DEFEAT 183

would leave them with empty guns,

foolish expressions, and a pair

of legs for running.

4. The colonial militia were the

better fighters. They almost

saved the day. The Virginians disrupted the British discipline

further and managed to save their own

skins. There is no reason

to suppose that they did much else. They

did not hold off a charge

by the French and Indians, because these

forces could not effectively

charge from their extended positions,

and besides they were having

too much fun as it was. The colonials

may have covered the retreat

of the British, but this was no great

service since the French and

Indians did not pursue. After all, the

French, Canadians, and Indians

were no great exception to their times;

all of them fought for a

living as a rule. There was no reason

why they should pursue an

enemy when there was so much loot lying

about on the bodies of

the dead who were left behind. Besides,

the idea of pursuit was un-

developed at this time. If the

Virginians covered the retreat, all that

that means is that they were not quite

as fast as the British in leav-

ing the field.

These are the only claims to glory that

the Virginians have,

and it is just as well to leave it at

this.

5. The British were surprised.34 For that matter so were

the

French. During the first few volleys

both sides were surprised. The

French were surprised not only at

meeting the British but also at the

fierceness of the British fire. The

British were surprised on exactly

the same counts. A quotation from

Clausewitz will help explain why

with this double surprise the side with

the fewer forces won the

battle. As Clausewitz said: "If one

side through a general moral

superiority is able to intimidate and

outdo the other, then it will be

able to use the surprise with greater

success, and even achieve good

results where properly it should come to

ruin."35

That is just about the essence of the

matter; the French and

Indians had moral superiority and they

intimidated the British.

British and colonial monkeyshines made

things easier for them, but

the victory went to the side with the

greater confidence and the

34 "We are not now speaking of the

actual raid, which belongs to the chapter on

attack, but of the endeavor by measures

in general, and especially by the distribution

of forces, to surprise the enemy, which

is just as conceivable in a defense, and which

in tactical defense is particularly a

chief point." Karl von Clausewitz,

On War

(Modern Library ed., New York, 1943), 142. Italics are

the author's.

35 Ibid., 645.

184

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

greater daring. It is apparent, then,

that the following conclusions

are justified:

1. During the first few minutes of the

fight it was the French

regulars who saved the French from

defeat. The French counterpart

of the Virginians, that is, the

Canadians, were among the first to leave

the field when the British opened fire.

This fact does not do much to

prove the vaunted superiority of

American militia over European

regulars.

2. Before going forward Braddock should

have found out

what was going on. Then he should have

arrived at the scene of

action in good order and in line of

battle.

3. If Braddock had wanted to win the

battle he should have

formed his troops and eventually ordered

a charge.

4. If he had wanted to lose the battle

or at best gain a stale-

mate, he could either have done what he

did do or else what the

Virginians wanted him to do.

5. The colonial tactics were not good

tactics in an absolute

sense. They were the tactics of men who

could not put a real army

into the field.

6. The tactics used by Braddock were not

good European

tactics.

7. There were two crucial points in the

battle. The stand of the

French regulars and the arrival of

Braddock in line of march. All of

the errors of the British stemmed from

these two points, the genius

of the French consisted in utilizing

them.

8. The morale of the French and Indians

was better than that

of the British.

9. And finally, if the proverb is true,

if desperate strength

does indeed make a majority, then

Braddock can be pardoned for his

defeat. He was outnumbered.