Ohio History Journal

FOLK MUSIC ON THE MIDWESTERN FRONTIER

1788-1825

by HARRY R. STEVENS

Duke University

Since the days when Frederic L. Ritter

and Oscar G. T. Sonneck

established modern musicology in the

United States between 1883

and 1910, two simple but rigid

traditions have dominated the writ-

ing of American musical history. One is

made up of the lives of

composers and performers, and

descriptions of their work. The

second and more important one is the

chronicle of musical or-

ganizations, performances, and

publishing. In few countries, how-

ever, has the work of the outstanding

musicians been of so little

relative importance in shaping the

course of musical history; and

the musical organizations that have

figured most prominently in

the chronicles often stood apart from

the main trend of musical

development-they were peripheral, even

exotic, rather than funda-

mental musical activities.

The broader currents of musical history

are scarcely mentioned

in most accounts of American music.

There are few descriptions

of the social and musical environment in

which composers, per-

formers, and audiences passed their

lives. Perhaps this is because

such matters seemed so obvious to those

who wrote the chronicles

that they thought it unnecessary to

explain them, assuming the

reader's familiarity; and subsequent

historians have simply copied

their material. The result in any case

has been that as personal

knowledge of that fundamental background

of social, cultural, and

musical life has died out with the

passing of successive generations,

the annals have tended to break into

detached fragments and to

lose much of their meaning.1 The

bricks were laid without mortar,

and the structure of musical

historiography is in danger now of

crumbling.

In order to repair this and to

understand contemporary Amer-

1 Frederic Louis Ritter, Music in

America (New York, 1883); Oscar George

Theodore Sonneck, Early Concert-life

in America (1731-1800) (Leipzig, 1907); Glen

Haydon, Introduction to Musicology (New

York, 1941), 247-265, 289-299.

126

FOLK Music 127

ican musical life historically, it is

essential to recover some knowl-

edge of the value of music to its former

listeners and performers

and its social role, as well as some

knowledge of the popular and

educated tastes and the musical idioms

of former times. Among

those matters the ever changing

relationship between popular idiom

and the work of creative artists has

seldom been explored, perhaps

chiefly because the general character of

American musical life in

any region a century or two ago is

largely unknown today. Until

that element has been established, it

will be difficult to under-

stand the significance of the facts so

carefully set down in tradi-

tional music histories. But before that

general character can be

described, its components must first be

reconstructed, among them

--perhaps the most basic-the story of

American folk song.

Generally speaking, the study of folk

music has followed the

narrow paths trod out by Cecil J. Sharp

and his followers thirty

years ago.2 It has been largely ethnological and

folkloristic: one

may discover, for example, that a

certain old woman in the moun-

tains learned some ballad as a child

from her grandmother, or

that a famous historic

"love-murder" was the basis for another

anonymous tragic song. There has been

scarcely any attempt to

represent the scope and nature of folk

music as a whole for any

time earlier than the present century.3

Perhaps the deficiency is explained by

the point of view that

Ralph L. Rusk expressed twenty years

ago. In Rusk's opinion

the history of folk song could scarcely

be written because the sub-

stance was ephemeral. Documentary

evidence was lacking in most

cases, and at best extended only to the

words, not to the tune.4 A

few musicologists have already shown

that such a dark view is no

longer necessary, and important

pioneering work has been done

by Percy Scholes, Phillips Barry, R. W.

Gordon, and George P.

2 Cecil J. Sharp and Olive Dame Campbell, English Folk Songs from the

Southern

Appalachians (New York, 1917).

3 Mellinger E. Henry, ed., Folk-Songs

from the Southern Highlands (New York,

1938); Emelyn E. Gardner and Geraldine

J. Chickering, Ballads and Songs of Southern

Michigan (Ann Arbor, 1939); Mary O. Eddy, Ballads and Songs

from Ohio (New York,

1939); Eloise H. Linscott, Folk Songs

of Old New England (New York, 1939); Paul

G. Brewster, Ballads and Songs of

Indiana (Indiana University, Publications, Folklore

Series No. 1, Bloomington, 1940); Ira W. Ford, Traditional Music

of America (New

York, 1940); Frank Luther, Americans

and Their Songs (New York, 1942).

4 Ralph Leslie Rusk, Literature of

the Middle Western Frontier (2 vols., New

York, 1926), I, 303-310.

128 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Jackson.5 But it is possible

to go still further and reconstruct, as

Edward J. Dent has recommended,6 an

entire folk-music culture,

in detail as well as in breadth, and

ultimately perhaps to recreate

that full story of public tastes and

attitudes which is basic to an

understanding of the course of American

musical history.

In starting such a task, it appears that

there has never been

any single focus of American musical

life concentrating or em-

bracing all its vital elements. To the

extent that a region or city

is outstanding, it is often different

and unrepresentative. How-

ever, a number of typical features may

be found in the cultural

area that has blended so many of the

traditions of American music

-the Middle West.

During the late eighteenth and early

nineteenth centuries Amer-

ican culture was highly homogeneous.

After 200 years of settle-

ment on the continent, before the great

tides of later European immi-

gration swept over the country with

their transforming impulses,

a clear pattern of life had come into

existence. During that period

the Middle West was passing through the

frontier stage. Elaborate

and exotic musical institutions were

lacking; but a remarkable

wealth of folk music was brought by the

people scattering westward

through the mountains; and a study of

the process and results

permits a comprehensive and balanced

survey that may answer

some of the problems of musical change.

One focus of the early westward

migration was at Cincinnati,

midway along the Ohio River. The

community was a typical fron-

tier village; and it was, in addition, a

gateway to the Middle West,

through which many thousands of pioneers

passed on their way to

the back country. It was not dominated

by any single cultural

group; and, as it was more stable than

towns like Lexington, Ken-

tucky, or New Harmony, Indiana, it was

also more representative

than they were. It has the added

significance of having been the

scene of Stephen C. Foster's work in the

1840's, when an enduring

and distinctively American music was

created.7

5 Phillips Barry, British Ballads

front Maine (New Haven, 1929); Percy Scholes,

The Puritans and Music in England and

New England (London, 1934); George

Pullen

Jackson, Spiritual Folk-Songs of

Early America (New York, 1937).

6 Edward J. Dent, "The Historical

Approach to Music," in Musical Quarterly,

XXIII, No. 1 (January, 1937), 13.

7 Raymond Walters, Stephen Foster:

Youth's Golden Gleam (Princeton, 1936).

FOLK Music 129

Cincinnati was established in 1788 by a

group of pioneers who

lived at first in caves along the river

bank. A log fort was soon

constructed in the wilderness there, and

a few rude cabins huddled

in its protecting shadow during the

early Indian wars. After the

Indian defeat at Fallen Timbers in 1794

a bucolic period lasted

until 1811. New homes were scattered

over the broad hill-rimmed

plain that now forms the basin of the city. Frame stores and

churches were built. While the

population increased about 2,000,

life moved at an easy pace.8

The War of 1812 interrupted the placid

existence of the town;

and after 1815 the renewal of westward

migration brought a flood

of settlers. The forests vanished from

the basin; the spires of

churches and the domes of the courthouse

and the college made

an urban silhouette. Steamboats crowded

to the public landing,

and an optimistic, energetic atmosphere

prevailed. By 1825 Cin-

cinnati numbered 15,000 inhabitants. It

had become the foremost

city of the Northwest, and had emerged

from the frontier stage.9

Here, then, in Cincinnati between 1788

and 1825 was a community

and a period the study of which may

disclose the possibilities of

this new inquiry.

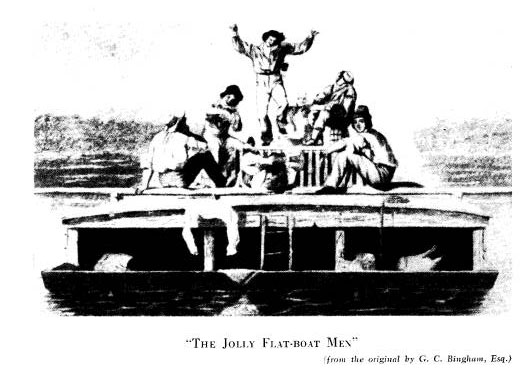

Early settlers of the western country

came by boat, and were

largely dependent on the Ohio River for

association with the out-

side world.10 The boatmen

themselves were a unique and adventur-

ous group of men, who afford the

earliest accounts of local pioneer

music.11 One of them, who had been a

rope maker in New Jersey,

entertained his passengers by singing to

them "half a day to-

8 Jacob Burnet, "Letters," in

Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, Trans-

actions, II, Part 2 (Cincinnati, 1839), 151-152; Beverley W.

Bond, Jr., The Civilization

of the Old Northwest (New York, 1934), 351-386, 424-464; Beverley W. Bond,

Jr.,

The Foundations of Ohio, Carl Wittke, ed., The History of the State of Ohio (6

vols.,

Columbus, 1941-44), I (1941), 295-300;

William T. Utter, The Frontier State 1803-

1825, Carl Wittke, ed., The History of the State of Ohio, II

(1942).

9 Jacob

Burnet, Notes on the Early Settlement of the North-Western Territory

(Cincinnati. 1847), 35-37; Edward D. Mansfield,

Memoirs of the Life and Services of

Daniel Drake (Cincinnati, 1855), 16-53, 130-137. Daniel Drake, Natural

and Statis-

tical View or Picture of Cincinnati

and the Miami Country (Cincinnati,

1815), 26-33,

129-168; Benjamin Drake and Edward D.

Mansfield, Cincinnati in 1826 (Cincinnati,

1827), 25-33, 88-91.

10 Western Spy (Cincinnati), June 2, 1815; Emerson Bennett, Mike

Fink: A

Legend of the Ohio (Cincinnati, 1848). All newspapers to which references

are made

hereafter were published in Cincinnati unless

otherwise indicated.

11 Morgan Neville, "The Last of the

Boatmen," in James Hall, ed., The Western

Souvenir a Christmas and New Year's

Gift for 1829 (Cincinnati, n. d.),

107-122;

Hiram Kaine, "Mike Fink," in

Charles Cist, comp., Cincinnati Miscellany; or Antiqui-

ties of the West (2 vols., Cincinnati, 1845-46), I, 31-32; Walter Blair

and Franklin J.

Meine, Mike Fink: King of Mississippi

Keelboatmen (New York, 1933), 39, 45, 64,

79, 99.

130 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

gether."12 A visitor from New England remarked that "almost

every boat, while it lies in the harbour, has one or more fiddlers

scraping continually aboard, to which you often see the boatmen

dancing."13

Another early traveler observed:

As the boats were laid to for the night in an eddy, a part of the crew

could give them headway on starting in the morning, while the others struck up

a tune on their fiddles, and commenced their day's work with music to scare

the devil away and secure good luck. The boatmen, as a class, were masters of

the fiddle, and the music, heard through the distance from these boats, was

more sweet and animating than any I have ever heard since. When the boats

stopped for the night at or near a settlement, a dance was got up, if possible,

which all the boatmen would attend.14

The music of the boatmen is not entirely unknown. One

pioneer mentioned "Blue Bells of Scotland" and Virginia reels;15

and another, describing his visit with Thomas Kennedy, the Cin-

cinnati ferryman, wrote: "Before we had finished our breakfast,

Mr. Kennedy drew a fiddle from a box and struck up Rothemurchie's

Rant. He played in the true Highland style and I could not stop

to finish my breakfast, but started up and danced Shantrews."16

The mellow boat horn was a pleasant and familiar sound; but after

thirty years the steamboat sounded the knell of the boatmen, and

the colorful group drifted away from the Ohio Valley.17

Ballads were known and sung by the pioneers, and western

soldiers made their own ballads on St. Clair's defeat in 1791 and

other incidents.18 Mothers sang to their children, who in turn

played counting, clapping, skipping, and dancing games with an-

cient music. James Finley, a pioneer western preacher, recollected

that in the 1780's or 1790's his mother had sung to him the war

songs of the century, including "Erin go bragh," "Hail to the

12 Benjamin Van Cleve, "Memoirs" entry for August 1, 1792, in Historical and

Philosophical Society of Ohio, Quarterly Publications, XVII, Nos. 1-2 (January-June,

1922), 40.

13 Timothy Flint Recollections of the Last Ten Years (Boston, 1826), 15.

14 "Western Keelboatmen," in American Pioneer, II (1843), 272-273.

15 Noah Miller Ludlow, Dramatic Life as I Found It (St. Louis, 1880), 35-38, 58,

84-85.

16 John Melish, Travels in the United States of America (2 vols., Philadelphia,

1812), II, 285-288.

17 Morgan Neville, op. cit., 120-122.

18 John B. Dillon, Oddities of Colonial Legislation in America (Indianapolis,

1879), 502-503, 547; Rusk, op. cit., I, 308; Matthew Bunn, The Life and Adven-

tures of Matthew Bunn (Buffalo Historical Society, Publications, VII, Buffalo, 1904),

434-436.

FOLK MUSIC 131

Chief," "Rule Britannia,"

and the "Marseillaise."19

Even the In-

dian music known in Cincinnati has been

described by pioneers,

one of whom mentioned two songs, "A

yaw whano heigh, how-wa-

yow-wa," and "Ha yaw

ki-you-wan-nie, hi yaw nit-ta-koo-pee."20

But the savage melodies can scarcely

have had much influence on

the songs of white settlers.

Before the end of the eighteenth century

at least fifteen tunes

were commonly known in Cincinnati. They

were airs to which local

poets set their verses, tunes proposed

for toasts, and other songs

heard in the village, or mentioned in

some way to indicate general

familiarity: "Jack the Brisk Young

Drummer," "The Vicar of

Bray," "Yankee Doodle,"

"Hark to the Midnight, Hark, Away,"

"Ca ira,"

"Gilderoy," "God Save the King," "He Comes! He

Comes!," "Banks of the

Dee," "Rose Tree," "Rule Britannia," "O

Dear What Can the Matter Be,"

" Done Over Taylor," "Here's to

Our Noble Selves, Boys," and

"Roslin Castle."21

During the next dozen years, until the

outbreak of the War of

1812, a total of eleven commonly known

tunes comprised all that

may certainly be included in the folk

music of Cincinnati. Two of

them have been mentioned in the

preceding list, "Yankee Doodle'

and "God Save the King," and

there were nine others not previously

identified in the town: "Bill Bobstay," "Wherever

She Goes,"

"Sweet Solitude," "Maggy

Lauder," "Mary's Dream," "Humors of

Glen," "Erin go bragh,"

"Jolly Mortals," and "Death's Cradle

Hymn."22

In the dozen years after the

commencement of the war 38

more tunes may be identified in

Cincinnati. In part this greater

number results from the growing size and

diversity of the popula-

tion; in part it is the consequence of

more abundant records. These

19 W. P. Strickland, ed., Autobiography

of Reverend James B. Finley (Cincin-

nati, 1854), 19-20.

20 Oliver M. Spencer, Indian

Captivity: A True Narrative of the Capture of Rev.

O. M. Spencer by the Indians, in the

Neighbourhood of Cincinnati (New York,

1834),

103, 105.

21 Centinel of the North-Western Territory, August 23, November 22,

1794, July

11, August 22, 1795; Western Spy, July

2, 9, August 27, October 1, November 5, 1799,

January 29, July 30, 1800; Claude M.

Newlin, Life and Writings of Hugh Henry

Brackenridge (Princeton, 1932), 256-257.

22 Western Spy, September

23, October 17, 1801, May 22, 1802, June 15, 1803,

May 15, 1805, August 26, October 14,

1806, April 13, August 24, 1807, November

16, 1811.

132 OHIO

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

tunes, not all

properly folk music, more than double the number

previously known in

the village:

Bandy O! Portuguese

Hymn

Lord Lennox Home

Sweet Home

Evelyn's Bower Anacreon

in Heaven

Mrs. Casey Geh

heim, mein Herz

John Gilpin Scots

O'er the Border

Paddy Snap Battle

of the Baltic

Crazy Jane Lafayette's

Grand March

Louis Gordon Ye

Mariners of England

Fly Not Yet Woo'd

and Married and A'

Hail Columbia Let

Fame Sound the Trumpet

Daintie Davie How

to Gain a Woman's Favor

McDonald's Reel Oh, 'Tis

Sweet to Think

Jackson's March March

to the Battle Field

Auld Lang Syne Malbrook

s'en va t'en guerre

Patriotic Diggers O Fie,

Let's A' to the Wedding

Begone, Dull Care I Have

Loved Thee, Dearly Loved Thee

Old Oaken Bucket My

Lodging's on the Cold Ground

Bright Chanticleer Ye Banks

an' Braes o' Bonny Doon

Hail to the Chief When I

Was a Boy in My Father's

[House?]23

The total number of

tunes identified in this way is 62.

Many problems of

folk-music history are apparent in this list.

About half the songs

are recognized today as folk music. "Gilderoy"

and "Banks of the

Dee," for example, were old folk songs known in

several versions under

various names. But others are of known

authorship.

"Patriotic Diggers" was written by Samuel Wood-

worth; "Hail

Columbia" was almost certainly written by Philip

Phile, and

"Anacreon in Heaven" by John Stafford Smith. Between

those two extremes

most of the tunes are of uncertain status. The

tune of "Rose

Tree" was taken with its title from an opera by Wil-

liam Shield, but seems

to have been known previously in Ireland

as a popular song,

"Maureen O'Cullenan."

"Oh, 'Tis Sweet to

Think" seems from

its name to be a sentimental drawing-room bal-

23 Western Spy, August 1, October 2, 1812, June 5, September 11, 1813,

October

4, December 13, 1816,

April 11, 1817, December 28, 1820; Liberty Hall, December

6, 1814, July 1, 1816,

June 14, 1825; Advertiser, June 23, July 28, 1818, October 26,

1819, September 3,

1822, April 7, July 19, 30, September 13, November 19, 1823,

January 17, February

21, March 13, June 23, July 7, 1824, January 29, May 4, 25,

1825; Gazette, April

27, 1819; Literary Cadet, January 20, 1820; Olio, I, No. 14

(November 24, 1821),

58; I, No. 21 (March 2, 1822), 84; Independent Press, August

8, 1822, September 11,

1823; Emporium, October 28, November 4, 1824.

FOLK

Music 133

lad. "Bandy O!" and

"Paddy Snap" in contrast are recognizably

popular Irish. But all three tunes

appeared in Moore's Irish Melo-

dies and were mentioned as "very fashionable"

among ladies of the

Atlantic cities, while another from the

same source, "Evelyn's

Bower," is identified in Grove's Dictionary

of Music as a popular

comic song in Dublin, "The Pretty

Girl of Darby, O!," a tune also

known later in Cincinnati as

"Landlady of France."24 The closeness

of this intermixture of tunes from

"folk" origins with those from

other sources is emphasized by the

manner in which they appeared

in Cincinnati. They were all marked by a

lack of association with

any individual composer or version,

assumptions of a general pub-

lic familiarity with the tunes, and an

implication that they were

common property.

Balls, dancing schools, and singing

schools provide further

clues to the exploration of folk music.

Even in the frontier wilder-

ness, dancing was not forgotten. There

was a ball at the log fort

on Washington's birthday, 1791; and the

same occasion was cele-

brated by the troops at Greenville,

Ohio, with "jocund song" on

February 22, 1796; while "a ball at

Head quarters, which the

Ladies of the village honored with their

presence, closed the joy-

ous scenes of this day."25 There

were many other such events. On

one further occasion Dr. Richard

Allison, an army surgeon from

New York, announced a Christmas ball in

December 1795 with the

dignity of "a Card" and

tickets of admission, thus evidently for the

first time locally placing dances on a

pecuniary basis.26

Dancing schools appeared a few years

later. Richard Haugh-

ton, a dancing instructor from

Pennsylvania and Virginia, informed

the villagers at Cincinnati in November

1799 that he would open a

school to teach "the minuet,

cotillion, French and English sets in

all their ornamental branches . . . the

most fashionable country

dances, and the city cotillions taught

in New York, Philadelphia and

24 Many of these tunes may be identified

by reference to Grigg's Southern and

Western Songster (Philadelphia, 1840) where titles and texts are

printed, and to the

works of Mary O. Eddy, Ira W. Ford, and

George P. Jackson cited in note 3, above.

25 Centinel, March 12, 1796;

Spencer, Indian Captivity, 29, 35.

26 Centinel, December 26, 1795.

Further details of Allison's obscure life may

be found in Burnet, Notes, 34;

Emil Klauprecht, Deutsche Chronik in der Geschichte

des Ohio-thales und seiner Hauptstadt

Cincinnati (Cincinnati, 1864), 138; Western

Spy,

November 19, December 3, 24, 1799, June

25, 1800, June 13, 1817; Liberty Hall,

November 15, December 6, 1814, March 25,

1816; Otto Juettner, 1785-1909. Daniel

Drake and his Followers; Historical

and Biographical Sketches (Cincinnati,

1909).

134

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

Baltimore," and added, "N.B.

Mr. Haughton also teaches some

favorite Scotch reels."27 Haughton

reopened his school in the fall

of 1800; but in April 1801 a local

resident mourned, "It is melan-

choly to observe the prevailing rage for

dancing schools; the nur-

series of idleness, frippery and

folly."28

It was five years before another dancing

teacher ventured to

advertise locally; but dancing persisted

in spite of objections.29

The "infamous" English

traveler Thomas Ashe reported in 1806

that "the amusements consist of

balls and amateur plays,"30 and in

the same year Garrett Lane opened a

dancing school, followed in

1808 by Mr. Coleman.3l Henry

G. Pies gave instruction on the

piano forte and violin in addition to

"the polite accomplishment"

of dancing in 1811; and two French

dancing masters, Colome and

Dusouchet, came in 1812 and 1813 to

teach the "Art of Dancing,

according to the rules of the most

approved seminaries of Europe."32

A crowd of dancing masters followed

those pioneers, but they pro-

vide little additional evidence of folk

music.

In less fashionable circles dancing was

more picturesque and

affords a better view of popular music.

Ashe described his experi-

ence of it as he stayed at an inn across

the Ohio River in 1806:

I entered the ball-room, which was

filled with persons at cards, drinking,

smoking, dancing &c. The music consisted

of two bangies, played by negroes

nearly in a state of nudity, and a lute,

through which a Chickasaw breathed

with much occasional exertion and

violent gesticulations. The dancing ac-

corded with the harmony of these

instruments. The clamour of the card

tables was so great, that it almost

drowned every other; and the music of

Ethiopa was with difficulty heard.33

On the north bank of the Ohio, a visitor

to Cincinnati denounced

the sleighing parties he saw in 1817,

which would proceed, unat-

tended by matrons, to some tavern three

or four miles from town,

27 Western Spy, November 19, December 3, 8, 1799.

28 Western Spy, October 29, 1800,

April 22, 1801.

29 Stephen S. L'Hommedieu,

"Inaugural Address," in Cincinnati Pioneer, No. 3

(April, 1874), 9-14; Daniel Drake, Notices

Concerning Cincinnati (Cincinnati, 1810),

Part II, 31; Daniel Drake, Natural

and Statistical View or Picture of Cincinnati and

the Miami Country (Cincinnati, 1815), 167; Liberty Hall, April 1, 1816 (an amusing

review of Drake's book), December 2,

1816; Western Spy, February 11, 25, March

4, 1815.

30 Travels in America Performed in

the Year 1806 (London, 1809), 182.

31 Western Spy, August

26, 1806, March 23, April 13, 1807, May 28, 1808.

32 Western Spy, August 3, 1811, March 18, April 4, 1812, September 17,

1813,

March 11, 1815; Liberty Hall, August

14, 1811.

33 Travels in America, 90-91.

FOLK MUSIC 135

where they would get out, set the

fiddlers to scraping, the girls to

dancing, and the boys to drinking.34 A native wrote a little differ-

ent account of a pirogue-sleigh ride

about 1810, "the American flag

flying, two fiddlers, two flute players,

and Dr. Stall as captain. They

did not forget to pass the 'old black

betty,' filled with good old

peach brandy, among the old pioneers,

and wine for the lady pion-

eers.... When the riding ended, both

young and old ... wound up

the sport with a ball."35

The singing school, an institution often

regarded as an im-

portant feature of frontier life,36

seems to have had a minor place

in Cincinnati. The first one was held in

1796, and there were others

in 1800, 1801, and 1806; but there were

apparently no more until

four were held between 1815 and 1822.

They were all inconspic-

uous, and provide little information of

folk music.37

A major place in the development of folk

music was taken by

religion, and its importance was

recognized more than a century

ago. A writer in the North American

Review in 1840 observed that

"music in America must be

surrendered to the people, must be

domiciled among them, must grow up among

them, or it cannot

exist at all.. .. There is more

hope, far more hope, that a national

music will grow out of the rude but

fervent hymns, with which the

overflowing congregations of Wesleyan

Methodists rend the heavens,

than that it will ever be reared by the

opera, or the costly concerts

of the nobility."38

There is little evidence of church

singing in Cincinnati until

1813, when a band of choristers sang at

the First Presbyterian

Church,39 and choirs were not

outstanding until after 1819.40 But

34 Liberty Hall,

February 3, 10, 1817.

35 Joseph Coppin,

"Cincinnati Pioneer Association Inaugural Address" (1880),

quoted in Charles T. Greve, Centennial

History of Cincinnati and Representative Citi-

zens (4 vols.,

Chicago, 1904), I, 463.

36 Catharine C. Cleveland, The Great

Revival in the West, 1797-1805 (Chicago,

1916), 11.

37 Freeman's Journal, December 17, 1796, cited in Bond, Civilization of

the Old

Northwest, 456; Western Spy, December 17, 1800, October 31,

1801, October 14, 21,

1806, October 25 November 1, 1816; Liberty

Hall, October 2, 1815, September 1, 4,

1817; Solomon Franklin Smith, Theatrical

Management in the West and South for

Thirty Years (New

York, 1868), 24-26; Samuel Stitt, "Recollections of Cincinnati Fifty

Years Since," in Cist's Weekly

Advertiser, October 5, 1847; "Early Jails, &c.," in Cist,

comp., Cincinnati Miscellany, I, 50-51.

38 "National Music in

America," in North American Review, L (1840), 13-15.

39 Liberty Hall, July 6, 1813.

40 Advertiser, January 27, 1823; Liberty Hall, April 2,

1824; Harry R. Stevens,

"The Haydn Society of Cincinnati,

1819-1824," in Ohio State Archaeological and

Historical Quarterly, LII (1943), 118-119.

136

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

from an early date there was a vigorous

controversy over the char-

acter of music to be used in the western

churches.

One side was represented in the

celebrated and popular Easy

Instructor of William Smith and William Little.41 The

hymn book

was sold in Cincinnati in 1811 and for

many years afterward,42 and

its popularity was admitted by

subsequent rivals.43 The Easy In-

structor represented the fuguing school and other late

eighteenth

century New England, New York, and

Pennsylvania composers,

particularly Daniel Read (1757-1836),

Elijah Griswold (fl. 1800-

1807), William Billings (1746-1800),

Timothy Swan (1758-1842),

Oliver Holden (1765-1834?), Oliver

Brownson (fl. 1783-97),

Morgan, Ward, Edson, Williams, Henry

Little, and Nehemiah Shum-

way (fl. 1793).

On the other side were Robert Patterson

in Pittsburgh and

Timothy Flint in Cincinnati. Patterson

in his Church Music wrote

of his alarm over "the levity and

ostentation" of the "light, rapid,

difficult tunes."44 Timothy Flint deplored "our merry

American

airs," and regretted that

"flighty and fuging music became the com-

mon taste" while "books of

another stamp could not be sold. ...

The composuist, it would seem, must have

had in memory some

march, or merry air that guides the

dance." Flint determined "to

give no quarter to trifling or fuging

music," however, and recom-

mended the solemn music of

"York," "Quercy," "Old Hundred,"

and "Canterbury." He worked

for the restoration of "the great

masters of old time": Luther,

Pleyel, Handel, Arne, Boyce, Madan,

and Purcell. His collection, the Columbian

Harmonist, favored

particularly Handel, Pleyel, Madan, J.

Clark, Arne, and Giardini.45

But many other tunes in his hymn book

were the anonymous popu-

lar products of the Reformation, which

he praised so highly for its

musical achievement.

41 The Easy Instructor, or, a New

Method of Teaching Sacred Harmony (Albany,

1807, 1809, etc.).

42 Western Spy, April 27, May 4, 11, 25, 1811.

43 Western Spy, October 23, 1813.

44 Patterson's Church Music,

Containing the Plain Tunes Used in Divine Worship,

by the Churches of the Western

Country (Pittsburgh, 1813; 2d ed.,

Cincinnati, 1815).

45 Timothy Flint, The Columbian

Harmonist: in Two Parts. To Which is Pre-

fixed a Dissertation upon the True

Taste in Church Music (Cincinnati,

1816). This

volume, of which apparently only three

copies remain in existence, "contains about 120

tunes, adapted to the churches in the

Western country." See pages iii, vii-xi. The

"dissertation" includes a

remarkable essay on musical history.

FOLK MUSIC 137

A paradox is thus apparent in this

conflict between ancient

hymns based on sixteenth century French

or German folk songs,

and those "merry American

airs" that have seemed to later histor-

ians so important in the development of

American folk music.46

An old stream of European folk music was

being suppressed while

a new one came into being from the

compositions of a local school

of American composers.

Theatrical music throws still more light

on folk song, and

particularly on the means by which it

was spread in the early nine-

teenth century. The first theatrical

performance in Cincinnati was

a comic opera, The Poor Soldier, written

by John O'Keeffe with

music by William Shield. It had been

performed in Dublin and

London in 1783 and in New York in 1786.

It reached Cincinnati

October 1, 1801, and was repeated in

1802 and 1811.47 The first

local production included a musical

interlude, consisting of an

original song to the tune "Wherever

She Goes." Theatrical produc-

tions followed irregularly from 1802 to

1815, and annually from the

latter year, often including comic

operas, musical farces, or other

musical entertainments. The diversions

produced with music before

1812 included The Poor Soldier,

Peeping Tom of Coventry, The

Agreeable Surprise, The Mock Doctor,

The Mountaineers, The Pad-

lock, The Poor Gentleman, Wild Oats,

The Old Maid, Love a la

mode, Animal Magnetism, The Wag of

Windsor, The Birthday, The

Romp, or a Cure for the Spleen, The

Spoil'd Child, and The

Weathercock.

In addition to the music provided for

these performances by

the band, there were fancy dances and a

variety of sentimental, pa-

triotic, and comic songs and duets. On

the stage Mr. Cipriani,

from Sadler's Wells, London, danced

hornpipes, and was assisted by

Mrs. Turner in a Polish minuet from Cinderella.48

The songs men-

tioned by name in theatrical

performances before 1818 were com-

paratively few:

46 George Pullen Jackson, White

Spirituals from the Southern Uplands (Chapel

Hill, 1933); Henry W. Foote, Three

Centuries of American Hymnody (Cambridge,

1940), 171-175; Raymond Morin,

"William Billings, Pioneer in American Music," in

New England Quarterly, XIV (1941), 25-33.

47 Western Spy, September 30, October 10, 17, 1801; Cist's

Weekly Advertiser,

September 14, 1847.

48 Western Spy, May 25, June 1, 15, 22, 1811; Liberty Hall, May

29, June 5,

12, 1811.

138 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

Madam Fig's Ball Country

Club, or the Quizzical Society

The Old Commodore Tid re I

[Bainbridge's Tedrei]

Father and I The

Way to Come Over

Decatur's Victory Lady

Camblin's Reel

Windsor Waltz How

to Please Woman

Turkish Hornpipe Marriage

of Miss Kitty Odonophon to

Yankee Doodle Mr.

Paddy O'Raffety

Battle of Tippecanoe

In 1813 a traveling

Irish musician, Mr. Webster, performed

"an

Entertainment, consisting of conversation, anecdote, and song,

called The Harp of

Erin at the Assembly Room in the Columbian

Inn," and

another entertainment called The Wandering Melodist a

few days later. He

presented an interesting mixture of Irish folk

music and popular

ballads of the day, and introduced several new

works to his

Cincinnati audience:

Fair Ellen The

Post Captain

Faithless Emma The

Glasses Sparkle

The Willow Honey

and Mustard

The Doldrum Why

Does Azure Deck the Sky

Far Far at Sea On

This Cold Flinty Rock

Sally Roy Come

Take the Harp

Exile of Erin Paddy

in a Pucker

Fly Not Yet Tell

Her I'll Love Her

Just Like Love Sweet

Lady Look Not Thus

Kathleen McChree Saint Senanus and the Lady

The Harp That Once

Through Tara's Halls49

A part of the process

of folk-music history emerged in the

sequence indicated by

Webster's concerts. Old English and Irish

folk songs and

favorite tunes by Irish minstrels were collected by

men like Edward

Bunting, provided with harmony by John Steven-

son and new words by

Tom Moore, lifted to another level of popu-

larity, and scattered

across Europe and America by traveling enter-

tainers, to gain new

vitality and still greater influence. The stage

seems to have been a

significant means of transmitting folk music

from one place to

another, and of prolonging its life. The very

process in operation

a few years later is confirmed and described

by Richard H. Dana in

Two Years before the Mast, under the date

April 24, 1836.

49 Western Spy, October

23, 30, 1813.

FOLK MUSIC 139

After 1818 the

information on theatrical music is so abundant

that only a selection

of representative songs can be listed:

The Tidy One Across the Downs This

Morning

Larry O'Gaff For Then I Had Not

Learnt to Love

Cherry Checked Patty The Soldier

Slumbering

William Tell The

Bewildered Maid

Bay of Biscay Who

Would Not Love

Sandy and Jenny Look,

Neighbors, Look

The Beggar Girl Scots

Wha Hae wi' Wallace Bled

Garland of Love Money

Is Your Friend

Jug, Jug, Jug Paddy's

Christening

The Bag of Nails Barney

Leave the Girls Alone

The Great Booby Megin O,

O Megin Ee

Pretty Deary Away

with This Pouting

All's Well Adieu

My Native Shore

Soldier's Bride And

Has She Then Failed

The Plough Boy Mr.

Peter Snout Was Invited Out

Eveleen's Bower You

Think No Doubt

London Fashions When First

I Left Sweet Dublin Town

Minute Gun At Sea Sir Jerry Go

Nimble, or Honey and

Mustard50

The titles once again

indicate a mixture of folk song and formal

composition, and the

problem of distinguishing them is complex.

Many composers

represented in this list, like Dibdin, Shield, and

Bishop, used a folk

song style, or simply adopted common tunes;

but their songs, even

those as popular as Shield's "Post Captain,"

usually did not

survive. The relation of ballad operas to folk

music, and especially

to the standardization of tonality and melodic

structure nevertheless

offers many clues to the history of folk song.

The process of

selection, rejection, and transmission of folk songs

seems to have been

strongly influenced by the education of taste in

the eighteenth

century. If it was not a creative period (which there

is some reason to

doubt), it was at any rate a time when many

earlier styles of

music were discarded.

Military music also

took an important role as an expression of

folk song and popular

taste on the frontier. Henry Brackenridge, a

western writer,

remembered General Wayne's camp near Cincinnati

in 1792 through

"the beating of drums, the clangor of trumpets"

50 Theatrical

advertisements in the local press, too numerous to cite in full, pro-

vide the source of

this information.

140

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

and the indistinct movements of horse

and foot amid the shadowy

forests.51 Fort Washington

was established at Cincinnati in 1789;

it remained there until 1808, but long

after its removal the influence

of military music was strong in the

pioneer village.

The army was provided with a drum and

bugle in each com-

pany of infantry and artillery, and a

cornet and trumpet in each

troop of cavalry.52 In 1806 a

troop of light dragoons met at Cin-

cinnati "to elect a Cornet in the

place of Mr. Stephen Ludlow, re-

tired."53 The old

records are full of details of music supplies, the

red uniforms faced with blue that the

musicians wore, and the pay

offered drummers and fifers, "$15

per month, and one ration per

day."54

But it was not until 1797, when General

Wilkinson arrived at

Cincinnati, that military music emerged

from obscurity. The new

commander brought an air of gaiety with

him, and apparently had a

band of musicians to enliven frontier

affairs.55 On July 4,

1799,

the toasts of the day were accompanied

by martial music and ar-

tillery;56 and at the memorial services

held for President Washing-

ton at the fort on February 1, 1800, the

music performed a solemn

dirge.57 The performances of the military band were described in

detail with the Independence Day

celebrations in 1801, 1802, and

1805, and a Republican victory dinner,

October 22, 1802.58 The

tunes played on such occasions were

often mentioned in reports of

the next twenty years. After the fort

was moved from Cincinnati

a band, possibly including some of the

former army musicians, was

active for many years. It played at

outings, in processions, at

51

Henry Marie Brackenridge, Recollections of Persons and Places in the West

(2d ed., Philadelphia, 1868), 17, 177,

184; Burnet, Notes, 157-158.

52 L. Belle Hamlin, ed.,

"Selections from the Torrence Papers, VIII," in Histor-

ical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, Quarterly

Publications, XIII, No. 3 (July-Sep-

tember, 1918), 83-85, 121, 130.

53 Western Spy, April 8, 1806.

54 Torrence Papers File, 48, fols. 57,

60, 65, in Historical and Philosophical

Society of Ohio, Cincinnati; Western

Spy, June 12, 1813, May 7, 1814; Liberty Hall,

March 18, 1816.

55 Lewis H. Garrard, Memoir of Charlotte

Chambers (Philadelphia, 1856), 35.

The local story that General Wilkinson's

band entertained dinner parties with the music

of Gluck and Haydn seems to have been

invented by Klauprecht, op. cit., 123, on

the basis of Brackenridge's recollections of Gallipolis,

Ohio. Frank E. Tunison, Prestol

(Cincinnati, 1888), 3-4; Heinrich A.

Rattermann, Early Music in Cincinnati, an essay

read before the Literary Club, November

9, 1879; Cincinnati Daily Gazette, May 15,

1880.

56 Western Spy, July 9, 1799.

57 Western Spy, February 5, 1800. This does not confirm the local

tradition that

the music was Phile's "President's

March." Tunison, Presto!, 3. It may have been

"Handel's Dirge," i.e., the

"Dead March" from Saul.

58 Western Spy, July 8, 1801, July 10, 1802, July 10, 1805, October 27,

1802.

FOLK MUSIC 141

memorial services,

banquets, formal celebrations in the churches

and at the courthouse,

and for special events. Contemporary ac-

counts offer pleasant

pictures of the townsfolk retiring with the band

to a beechen shade,

where sports and rural pastimes filled the day

until dinner was

served, and numberless toasts and songs filled the

night.59

About 100 tunes played

by the band in Cincinnati have been

mentioned in surviving

records. By far the most popular were

"Hail

Columbia," "Yankee Doodle," and "Washington's March,"

with almost twenty

performances for each. Not far below them in

popularity were four

other tunes, "Anacreon in Heaven" (which

had not yet become the

national anthem, although it was played

here as "The Star

Spangled Banner" in 1819), "The President's

March" (perhaps a

composition of Philip Phile to which the words

of "Hail

Columbia" were later written), "Fair American," and

"Come Haste to

the Wedding."60

In addition to those

six or seven tunes there were nineteen

others mentioned with

three to five performances each:

Reveille Guardian

Angels

Marseillaise Rural

Felicity

Stoney Point (five

times each)

Ca ira Sprig

of Shillelah

Erin go bragh Madame

You Know My Trade Is War

Jove in His Chair God

Speed the Plough

Hail to the Chief French

Grenadier's March

Jefferson's March (four

times each)

Rogue's March General

Harrison's March

Jackson's March Money

in Both Pockets

Successful Campaign (three times

each)

The list may be

extended with nineteen tunes that were played at

least twice each by

the band during this period:

Dead March Love

in a Village

Friendship Flowers of

Edinburgh

Soldier's Joy Indian Philosopher

59 Western

Spy, July 10, 1805.

60 Western Spy, July 8, 1801, July 10, October 27,

1802, July 10, 1805 July

11, 1812, July 11,

1817; Inquisitor, July 7, 1818, July 13, 1819; Advertiser, July

13,

1819, March 19, 1822,

March 19, 1823, March 20, 1824, March 19, May 25, August

17, 1825; Independent

Press, July 10, 1823; Literary Cadet, July 8, 1824; Liberty

Hall, July 9, 1824.

142 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Turk's March Volunteer's March

White Cockade On the Road to Boston

Roslin Castle Life Let Us Cherish

Columbian March Will You Come to the Bower

Exile of Erin America, Commerce

and Freedom

Liberty Tree Good Night an' Joy

Be With You A'

Soldier's Return

The last and most

numerous group of band tunes is made up

of the pieces with

only a single known performance:

Hill Tops Patriot's

Cotillion

Grand Spy Janissaries'

March

College Hornpipe Battle of Prague

The Jolly Tar New President's March

Hearts of Oak Soldier's March

Banks of the Dee Italian Waltz

Soldier's Adieu Masonic Dead March

Tippecanoe Lafayette's March

Tars of Columbia Sweet Harmony

Monroe's March Pleyel's Hymn

Hull's Victory Victory of Orleans

Adams and Liberty Liberty or Death

Haydn's Fancy March in Blue Beard

Echo Miss

Ware's March

Liberty March Harmonical Society's

March

Lawrence's Dirge Handel's Dirge

Mechanic's March Spanish Patriots

Ode on Science City Guards' March

Clinton's March Jefferson and Liberty

Hail Liberty Fire on the

Mountains

The Wounded Hussar Cincinnati Guards' March

The Dusty Miller Governor Tompkins' March

Cease Rude Boreas Away with Melancholy

Tune of '76 The Meeting of the

Waters

The General Malbrook s'en va

t'en guerre

Bunker's Hill Columbia, Columbia

to Glory Arise

Kentucky Reel Scots Wha Hae wi'

Wallace Bled

Blythe Sandy When Bidden to the

Wake or Fair

Assembly

Among the 100 band

tunes known in Cincinnati a considerable

number, including

"Hail Columbia," "Yankee Doodle," "Anacreon

in Heaven,"

"Ca ira," "Erin go bragh," and "Roslin Castle"

were

also familiar through

the theater or other institutions. Some of

FOLK MUSIC 143

them were repetitions under various

names: "Hail Columbia" seems

to have been "The President's

March"; "Anacreon in Heaven" was

also known as "The Star Spangled

Banner" and as "Adams and

Liberty"; "Haste to the

Wedding" was given the title of "Rural

Felicity" and was also renamed

"Perry's Victory" after the naval

triumph on Lake Erie; and the topical

names of other songs and

marches suggest old tunes with new

labels.

Some of them are certainly not folk

music. "America, Com-

merce and Freedom" was written by

Alexander Reinagle; "Dead

March" was possibly the march from

Handel's Saul; "The Wounded

Hussar" was written by James

Hewitt; and "Echo" may have been

Henry Rowley Bishop's "Celebrated Echo

Song." "The Battle of

Prague" was probably the

composition of Kotzwara mentioned in

a poem by Thomas Hardy. "Haydn's

Fancy," "Handel's Dirge,"

"Pleyel's Hymn," and the

"March" from Blue Beard are obviously

the works of individual composers. But

folk music cannot be re-

stricted to such familiar forms as

ballads and reels without exclud-

ing many works of similarly obscure

origin--for example, the an-

cient military bugle calls,

"Assembly" and "Reveille." The problem

of identifying tunes by name is a

difficult one, but not insoluble.

Questions of that sort may often be

settled by reference to song

books and to the elaborate tune

genealogies that recent folklorists

have established.61

One of the most interesting features is

the extent to which

national characteristics are

recognizable in the music or titles. The

"Marseillaise" and "Ca

ira" are clearly French, and "Geh heim,

mein Herz" German; Scotch tunes are

identifiable in "McDonald's

Reel," "Auld Lang Syne," "Ye

Banks and Braes," "Scots O'er the

Border," "Blue Bells of

Scotland," "Hail to the Chief," and "Rothe-

murchie's Rant."62

The Irish seem to have made the largest

distinctive contribu-

6l See Jackson, Spiritual Folk-Songs; Eddy, Ballads and Songs

from Ohio; Brewster,

Ballads and Songs of Indiana; Samuel Preston Bayard, Hill Country Tunes,

Instrumental

Folk Music of Southwestern

Pennsylvania (American Folklore

Society, Memoirs, XXXIX,

Philadelphia, 1944),

"Introduction," xi-xxvii.

62 Just after the close of this period a

celebration of St. Andrew's Day by the

Scots Society of Cincinnati, December 1,

1828, included many other typical songs:

"Here's to the Land o' Bonnets

Blue," "The Kail Brose o' Auld Scotland," "Take Your

Auld Cloak About You," "Up an'

Waur Them A' Willie," "Bannockburn," "Thistle

So Green," "Burns'

Farewell," "Hail to the Chief," "Bonnets Blue,"

"Scots Wha

Hae," and "My Mither She

Mended My Breeks." Cincinnati Daily Gazette, December

3, 1828.

144 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

tion of folk tunes.

Many Irish tunes were adopted by the com-

munity at large, among

them "Haste to the Wedding" and "Sprig of

Shillelah." In

addition to those there were over two dozen tunes

that were used in

Cincinnati exclusively by the Irish, in connection

with celebrations of

St. Patrick's Day before 1825. Four of them

were often

repeated: "St. Patrick's

Day," "Granu wale," "Vive

la," and

"Carolan's Receipt--for the Making of Whiskey." Twenty-

two other tunes are

known to have been used once each by the Irish,

and apparently by no

one else in Cincinnati during this period:

Merryman O

for the Sword of Other Times

Cincinnati Forget

Not the Field

Molly Astor Garry

onne [Garry Owen]

Coolin Remember

the Glories of Brian the

Brave

Paddy Carey The Harp That Once through

Tara's

Halls

The Farmer What

Makes the Ladies Like It So

Madison's March Willy Was

a Wanton Wag

The Philosopher Universal

Emancipation

The Galley Slave Constitution

and the Guerrierre

Jessy O'Dumblaine The Banks of

the Ohio

Tantararu Rogues All O Breathe Not His

Name63

It is impressive in

looking over the Irish tunes to notice the great

variety of style and

form represented by songs from Edward Bunt-

ing's General

Collection of Ancient Irish Music (1796), Thomas

Moore and John

Stevenson's Selection of Irish Melodies (1807-15),

and Turlogh

Carolan's Favorite Collection of Irish Melodies

(1747?).64

It is evident that in

the late eighteenth and early nineteenth

centuries there were

at least five levels of folk music assimilation.

63 Advertiser, March 19, 1822, March 19, 1823,

March 20, 1824, March 19, 1825.

64 William H. Grattan

Flood, A History of Irish Music (Dublin, 1927), 227 et.

seq. See also Donal O'Sullivan, "The Petrie Collection

of Irish Folk Music," in

Journal of the English Folk

Dance and Song Society, V, No. 1

(December 1946), 1-12,

and John Parry,

"The Earlier Collections of Traditional Welsh Melodies," in Cylch-

grawn Cymdeithas

Alawon Gwerin Cymru, III (No. 9) Part

I (1930), 12-18, and III

(No. 10) Part II

(1934), 103-108.

Some of Moore's tunes

were ancient Irish folk songs; many others that were

equally popular and widespread

show evidence of highly individual authorship, such

as "Fly Not Yet,"

which was Carolan's "Planxty Kelly." The intricate history of Irish

folk music in the

eighteenth century has never been disentangled; until it is, little

can be said with

certainty about the history of Irish folk tunes in America. The same

is true of Scotch and

Welsh folk music. For example, "Roslin Castle," which might

seem from part of its

history to be a Scotch tune, was actually composed by the

eighteenth-century

Welsh musician Greg Wen, or Garry Owen, who was honored on

St. Patrick's Day by

the Irish.

FOLK Music 145

There were songs now accepted as folk

tunes, such as "Lord Lennox"

and "McDonald's Reel" and true

folk songs adapted or supplied

with fresh words; recently composed

ballads or theater songs based

on folk tunes, from "The Wounded

Hussar" and "The Post Cap-

tain" to "Rose Tree" and

"Eveleen's Bower"; songs of a definite

"folk" character but with a

putative authorship, among them many

Irish and Welsh tunes by Garry Owen and

Carolan, given new cir-

culation by Bunting or Moore; songs of

apparently recent origin

and individual although unknown

authorship, such as "Yankee

Doodle"; and songs whose composers

are known, such as "Rule

Britannia" (Thomas Arne),

"Anacreon in Heaven" (John Stafford

Smith), and "The President's

March" (Philip Phile), which were

as widely current as folk music but

markedly individual in style.

It is also apparent that there was by no

means a complete

fusion of tunes from various European

sources, but that the Eng-

lish and Scotch tunes provided a broad

foundation to which others

were added without at first making a

fundamental alteration. Words

as well as names were being modified to

fit American requirements,

however; English associations were being

shed, and a body of folk

music specifically associated with the

American scene was already

well established, while the folk

elements, especially from Irish

tunes, in the sentimental, comic, and

patriotic balladry, point toward

a fusion that was to evolve a new folk

style.65

A good bit of the nature of folk music

in America may be illu-

minated by this fragment of its history.

In origin, most of the tunes

current at Cincinnati from 1790 to 1825

bear the characteristics of

the middle eighteenth century. Earlier

elements such as the tune

"Coolin" appear incongruous,

and stand out in contrast to the other

folk tunes and similar compositions of

Arne, Shield, Storace, and

their contemporaries. There are hints

that folk music in the British

Isles passed through a revolutionary

development between 1640 and

1740, possibly under the influence of

obscure musicians of that

century.

It would be hard to distinguish between

some of the anonymous

65 Jackson, Spiritual Folk-Songs; "Stephen

Foster's Debt to American Folk-Song,"

in Musical Quarterly, XXII,

No. 2 (April 1936), 154-169; Foote, Three Centuries of

American Hymnody, 171-175. An excellent account of the background of Foster's work

is given in Walters, Stephen Foster, 59-68.

146

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

tunes of the eighteenth century and

others whose composers are

known. While there are clear differences

between some English,

Irish, Scotch, and Welsh tunes, there

are numerous others that can-

not be labeled with national origins.

It would seem from a review of popular

music on the Midwest-

ern frontier that folk song was passing

through a lively history,

obscure, but none the less real. Efforts

to trace tunes to an absolute

primitive germ in the same way that

efforts were once made to

isolate pure primitive races or

languages have a definite value; but

the representation of the full popular

background and the processes

of historic change promise even more

toward an understanding of

the nature of folk music and the

appreciation of all American mus-

ical history. Three things that seem

here to be most significant for

such understanding are the work of the

minor composers of the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,

the education of popular taste

through church, camp meeting, theater,

tavern, song book, military

bands, and other institutions, and the

influence of taste on the selec-

tion, transformation, and transmission

of folk songs.